How to Identify Burnt Villages by Satellite Imagery — Case-Studies from California, Nigeria and Myanmar

Evidence of human rights abuses often remains in some of the world’s most regional and unreachable parts.

It is in these areas, where a view from satellite imagery above can be the sole method of visual evidence of bombings, attacks, and the destruction of communities.

As satellite imagery becomes more available and technology permits for more access, we are seeing overhead mapping play more of an integral role in media and human rights bodies to identify a chronological story of an area.

For some areas, this may be through infrastructure expansions, military operations, or what new equipment has just landed on the tarmac. For other parts, satellite imagery can reveal signs of chemical attacks or villages that have been burnt to the ground.

While this imagery does help, it does not replace evidence obtained from the ground — but it goes a long way to help us know what happens in these conflict areas.

Creating a Fire Damage Reference Scale with Google Earth

Satellite images courtesy of Google Earth / DigitalGlobe.

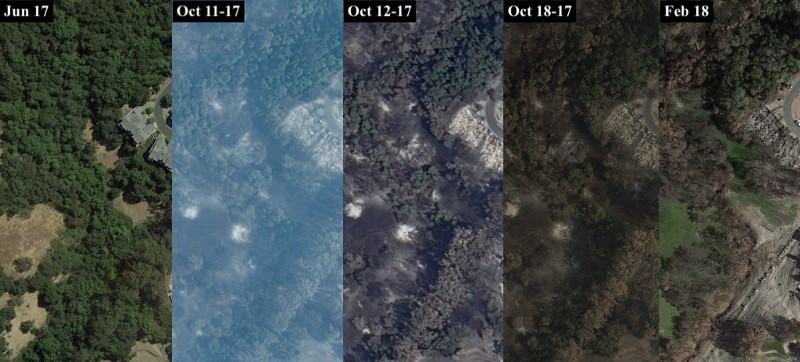

As a reference point for what fire damage looks like on satellite imagery, we can use California’s devastating 2017 fires as a litmus scale.

The above images are available on Google Earth and are from Coffey Park, a suburban area in Santa Rosa, California, that saw widespread destruction of houses, buildings, and bordering reserves.

In the chronological satellite timeline above, you can see specific signs that a fire has taken place. These are signatures left on the earth when damage has been caused by fire, namely:

- Blackening of the earth where any grass or shrub once stood

- Levelling of infrastructure exposing its foundations

- Clear white patches formed by beds of ash

The most significant of these indicators to appear on imagery are the white patches of ash left behind, as you will see, these are significant markers when scanning more remote areas for signs of attacks against people and their homes.

There are also other ways to confirm fire damage in satellite imagery, for this we can use Sentinel Hub to determine vegetation levels and other useful options.

Using Sentinel Hub to Confirm Fire Damage

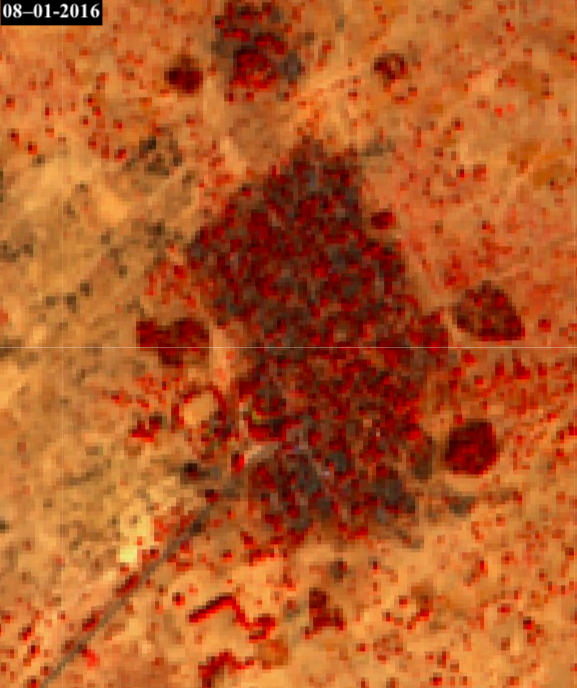

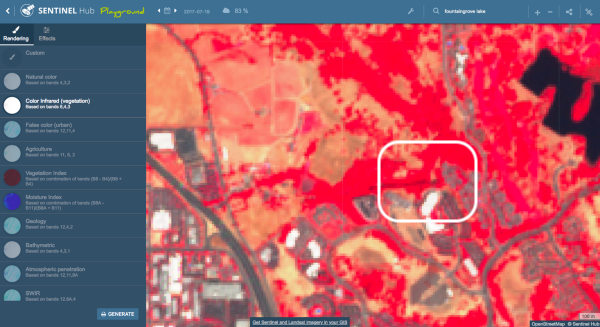

Sentinel Hub’s playground feature has a number of interesting rendering options on its satellite imagery.

A number of these can support our findings of fire damage. In the example above of the same urban area in Coffey Park, Santa Rosa, we can view the “Color Infrared (vegetation)” band on the satellite imagery.

The zoom level is limited in Sentinel Hub, however using this filter to identify vegetation reveals a significant difference between pre-burn and post-burn. For widespread bushfires such as California’s fire, much of the red vegetation was burnt and destroyed, but there is a definite change in the level of bright red to a much darker image, indicating a significant loss of vegetation.

This change in vegetation levels is illustrated in the images below. At the top is the concentration of vegetation in our area in Coffey Park from July, 2017, while on the bottom is the vegetation from October, 2017, after the fire had swept through.

Using these open source tools, we can find, identify, and analyse areas that have been caused by means other than natural causes.

Identifying Villages Destroyed by Fire

Context also plays an important role in satellite imagery, as these overhead views will only go so far as to tell us that a building, hut, or community, has been destroyed.

They will not tell us how it has been destroyed, or why, but using evidence from satellite imagery provides us with a firm timeline from which we can base our search filters on.

This is where open source information, through the use of reports from non-governmental organisations (NGOs), human rights bodies, news agencies, and social media, in conjunction with satellite imagery, will create a much better picture of what has occurred.

In Musari Village, east of Maiduguri in Nigeria’s Borno State, we can see evidence of damage to a number of the village’s huts.

The area surrounding the village is dry with a lack of vegetation, therefore we do not see the blackening of the earth as widespread as in the Californian fires examples. However, it is evident that the small hut infrastructure has burned, leaving ash markings.

In a closer view, we can see more of those signature markings.

Correlating this with a Google search using the given dates on the satellite imagery indicate that this is an attack by Boko Haram militants.

Dalori (below), also near Maiduguri in Nigeria, shows evidence of more permanent structures that have been destroyed by fire.

Using Sentinel Hub’s vegetation feature, we can further highlight the changes we see on Google Earth.

Sentinel Hub imagery is also more frequently updated than Google Earth satellite imagery, so we are able to narrow down dates using these features.

To substantiate the damage, a comparison between two dates can be made to see what has changed in this village.

As you can see below, the area is the same, but on a chronological scale, they are completely different. Roofs are missing, walls destroyed, significant trees burnt and there is a blackening of the earth around the structures, indicative of scorching.

Running a chronologically filtered Google search between these dates provides us with reports of scores of children and adults that were burned to death in this village by more than 80 militants.

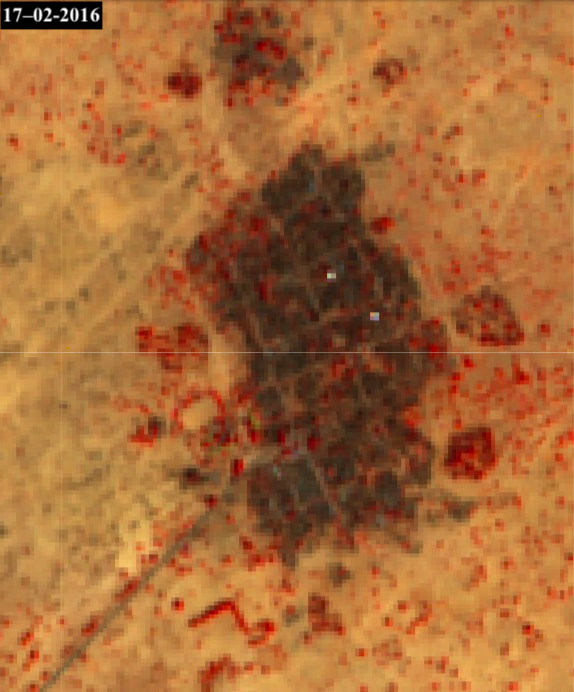

Using the Burned Village Litmus on Myanmar

As a standard approach, reporters and human rights researchers can use these tools to identify clear abuses, in conjunction with contextual information.

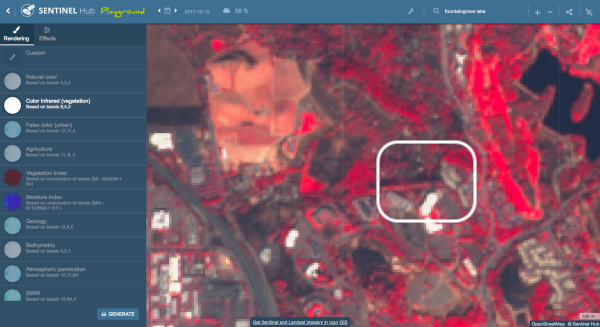

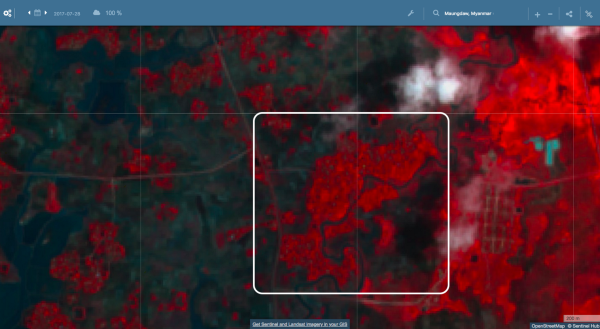

For instance, in Myanmar’s Rakhine State, where mass village destruction has been reported, the signs of village destruction are very evident.

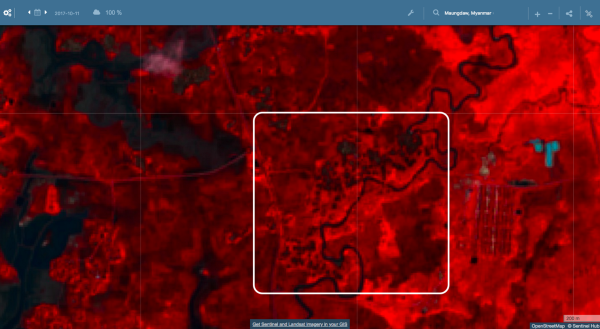

Using Sentinel Hub, it is very easy to determine where fire has caused a rapid decrease in the vegetation count. You can see this in the following satellite imagery with the view at the top from July, 2017, and on the bottom, from October, 2017.

As we can see in Sentinel Hub, vegetation can reveal where fires have been, whether it is in a Nigerian desert environment such as in the previous examples, or in a more vegetated environment such as Myanmar.

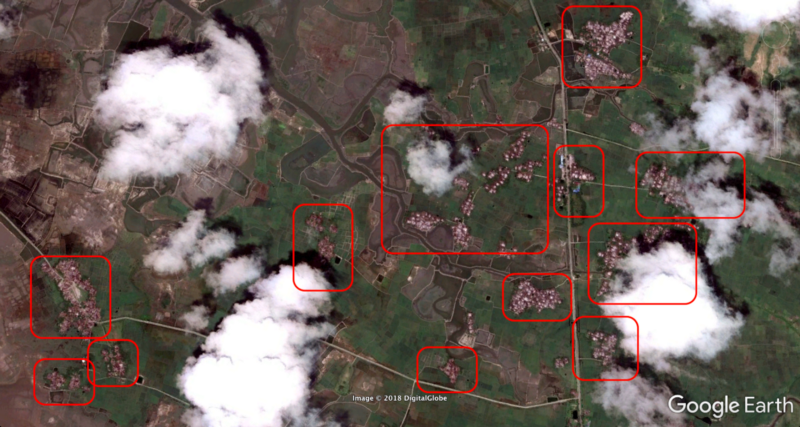

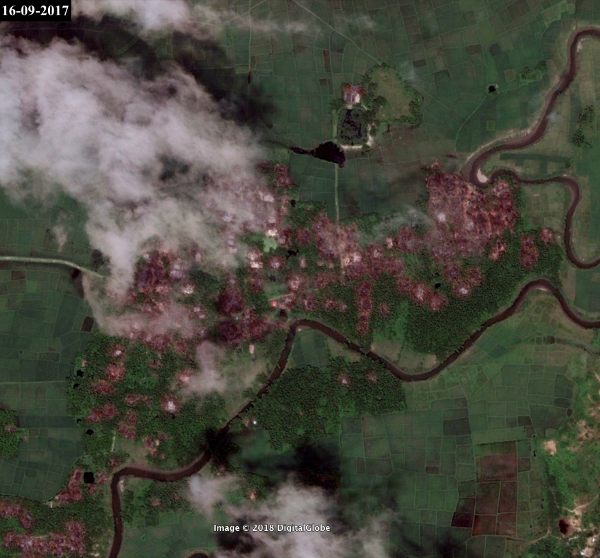

Taking a closer look at Google Earth imagery provides a more clear image as to the destruction of the overview of villages in the Rakhine State.

In a closer look, we can see the same aspects that both the natural Californian fires had, as well as the deliberately burnt villages in Nigeria.

These signature traits of white spots of ash, charred ground and a substantial decrease in vegetation (both visually and via band imaging) are present in all markings of burnt villages.

All in all, satellite imagery allows anyone with an Internet connection to identify potential evidence of new human rights abuses, and such open-source information — from Google Earth or Sentinel Hub — and may just as well assist media and human rights organisations to verify such claims.