Quantum of Obfuscation

On the day the Dutch Safety Board released its final report into the causes for the crash of Flight MH17, the Russian Foreign Ministry issued a statement that the “report is flawed, as the Russian findings were not taken into account”. This statement followed numerous assertions by Russian diplomats that Russia “is kept out of the loop of the investigation” and that the investigation is “not independent, not comprehensive, and not truly international”. Similar sentiments were expressed during the pre-emptive press conference by the state-owned Buk manufacturer Almaz-Antey preceding the report’s publication, as well as in the follow-up press conference by RosAviation, the Russian air-safety agency.

MFA: Russia will study Dutch MH17 report, but it was flawed, as Russian findings were not taken into account. pic.twitter.com/uu7cuVkUAF

— Russian Embassy, UK (@RussianEmbassy) October 14, 2015

However, as becomes evident from Dutch Safety Board (DSB) 835-page report, the Russian Federation was one of the more active contributors to the joint investigation team, and on many occasions was more successful in influencing the content of the final report than other involved parties, including the Netherlands’ own Foreign Ministry (none of whose suggestions were honored in the final report). At the same time, the report and its appendices makes it clear that Russia withheld vital information from the investigation, despite explicit requests for its disclosure. Most importantly, the sequence of inputs provided implies a mid-way change of heart in Russia’s position relating to the MH17 investigation.

Most of this comes to light from the 50 page consultation matrix – a summary of the requests for changes to the draft report, as proposed by each involved party, and the corresponding reaction by the Dutch Safety Board. The consultation is a legally required step of public safety inquiries, under both the Chicago Convention and Dutch law, which must take place between the delivery of the draft report to the concerned parties, and the publication of the final version.

Degrees of Involvement

Despite Russia’s complaints of isolation from the progress of the investigation, it participated in all three interim-progress meetings held by the DSB and provided a total of 74 written comments in the consultation process between the draft and the final report. Nineteen of these comments resulted in amendments of the report’s text, with varying degrees of significance. This puts the Russian Federation at the top of the “amendment contributors” list, both in absolute number of inputs and as success ratio. In comparison, the Netherlands provided 38 comments, with zero success in influencing the DSB to change the draft text, while Ukraine provided 46 comments, and was able to achieve [largely stylistic] changes in only 3 cases.

There were far fewer comments from the other involved parties, with Malaysia providing only 3 comments.

Russia’s comments significantly differed from all others not only in quantum, but also in scope. The Dutch comments largely referred to the safety and liability aspects of the report. For example, the Dutch Foreign ministry sought to remove the language on the responsibility of Ukraine over not closing its airspace, as it thought there was not sufficient evidence of presence of separatist-held weaponry that could reach into commercial airline altitudes. The DSB snubbed this request. Ukraine also attempted – unsuccessfully – to soften the report’s language on its moral responsibility, but mostly sought to change the vocabulary used throughout the report: it insisted on Crimea being referenced as “Ukrainian territory under temporary occupation,” and the “rebels” being referenced to as illegal armed groups. The DSB was not sympathetic to any of these requests, insisting that it will use politically neutral language.

Armed Factions, No Russians.

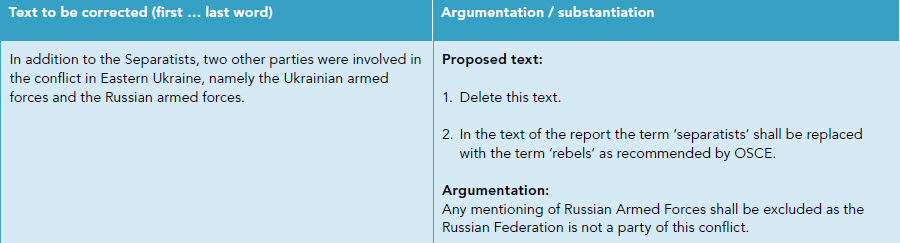

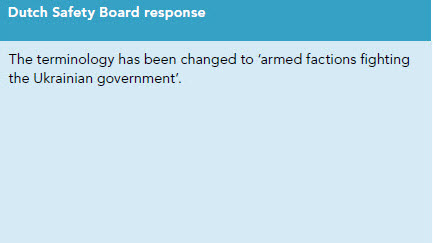

Russia was more successful than Ukraine in modifying the political vocabulary used in the report. From the consultation matrix, it becomes clear that the original draft report included references to “Russian armed forces” as a third party active in the military conflict in Eastern Ukraine[1]. Russia not only requested the deletion of this reference, but required that the reference to “separatists” be replaced with the Russian-preferred term “rebels.” The DSB honored both of these requests, and modified the text accordingly. In a snapshot of the appendix below, the first image shows the Russian-requested changes to the text, and the second image shows the DSB’s reply to the Russian request.

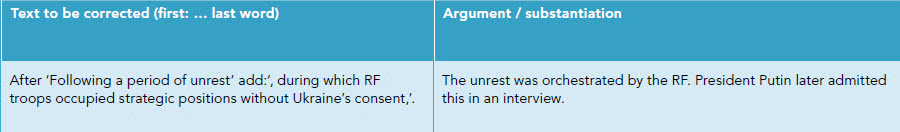

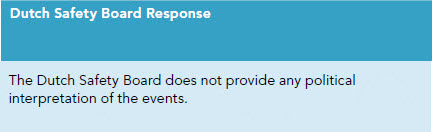

At the same time, requests by the Dutch Foreign Ministry to make explicit Russia’s military role in stirring up the events leading to the annexation of Crimea were declined. The first image shows the Dutch Foreign Ministry’s request.

Aside from political stylistics, Russia’s comments were much more far-reaching than any other consulted party, as they sought to modify the substantive conclusions of the DSB as to the cause of the crash. In particular, Russia wished to make the report much less deterministic than the draft report it had seen in July. To this end, Russia even changed its position on issues it had already subscribed to during the first and second interim progress meetings.

Ambivalent Parallelism

During the first progress meeting, held at the Gilze-Rijen airbase February 16-25 2015, accredited Russian representatives too part in a review of the Boeing’s wreckage. At the conclusion of the week-long investigation, a plenary meeting of all parties – including Russia – reached consensus that “the aeroplane was most likely downed by a missile that was launched from the ground”.[2] Before adjourning, all parties agreed on the aspects requiring further investigation.

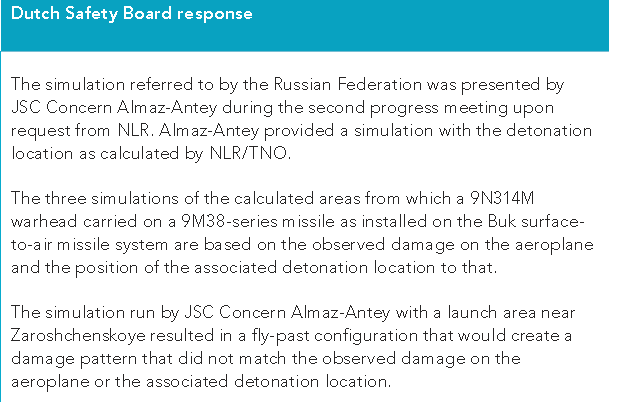

The second meeting was held on May 6-7, and the Russian delegation attended again. After another review of the wreckage, and following up on the previous meeting, the parties focused on the possible types of weaponry used, and its likely ballistic trajectory. During this meeting, two contradicting simulations were presented as to the possible trajectories of the missile: one by the Dutch Aeronautics Institute (NLR), and another by Almaz-Antey. Both presentations assumed a Buk missile, but differed in trajectory simulation, due to the different assumption regarding the angle of approach of the missile to the airplane. Yet, this progress meeting ended with yet another, consensual conclusion that the Boeing had been hit by a surface-to-air missile. The sole dissenting opinion, by Russia, took exception only to the Dutch reconstruction of the trajectory, but not to the type of weapon.

A day prior to Almaz-Antey presenting its simulation results in the Netherlands, its report was leaked to the opposition Russian paper Novaya Gazeta (not infrequently used by the Kremlin as a leak platform). The full presentation of the Almaz-Antey analysis was officially published by TASS nearly a month later.

At this point, the Dutch investigation team assumed that Russia, indeed, had conclusively subscribed to the “ground-to-air” hypothesis. The DSB then proceeded to present its draft report to all parties concerned – including Russia – on June 2nd. The draft report elaborated on the consensual “ground-to-air” hypothesis, and included the Russian dissenting opinion as to the missile’s trajectory, accompanied with a copy of the Almaz-Antey report, as appendix. Furthermore, sources familiar with the draft report confirmed that it addressed the impossibility of Almaz-Antey’s assumption about the missile’s approach angle, based on – inter alia – triangulation of ultrasound peaks captured by the cockpit audio recorders, which confirmed the missile’s direction of approach.

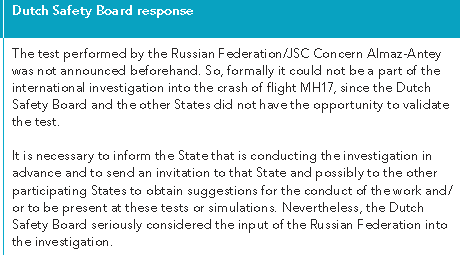

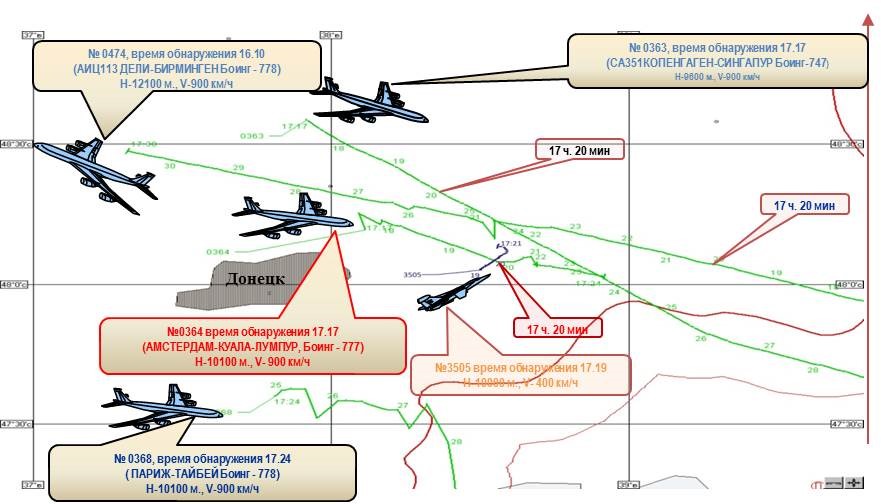

Following the receipt of the draft report, the Russian position changed. During the third and final progress meeting, held August 11-12, 2015 in Gilze-Rijen, Russia surprised the joint team with an unannounced presentation of a “Russian ballistic study,” which sought to turn back the investigation’s clock to a far less deterministic stage. In particular, Russia presented the results of an empirical experiment, conducted by Almaz-Antey on bow-tie shaped shrapnel fragments, which sought to prove that one fragment found by the Dutch team and weighed by the Russians during the first meeting,was too light (at 5.5 g), compared to those shot by Almaz-Antey through aircraft-type metal plates in their empirical test (at 7.2 g). The Russian ballistic presentation continued to conclude that based on the evidence, flight MH17 might have been shot down by either a Buk ground-to-air missile, or by an air-to-air missile.

The DSB team rebuffed the Russian re-introductions as being unverifiable, unannounced, and conducted outside of the official investigation process. More substantively, the DSB stated that it is improper to compare ground-based experimental results to expected outcomes at an altitude of 10 km, with different air-density and a non-stationary airplane.

From the content of the consultation matrix, it appears that Russia attempted to remove all traces of its prior endorsement of the ground-to-air hypothesis. Russia insisted on a complete removal of all references to the Almaz-Antey presentation made during the second meeting. It stated that the Almaz-Antey report and trajectory computation had had the relevance of a tentative scenario; i.e. “only in the event that it were a ground-to-air missile, would the trajectory had been such and such.”

The DSB consented to treat this as a misunderstanding and to remove the original Almaz-Antey presentation and references to it.

Two Russian trajectories?

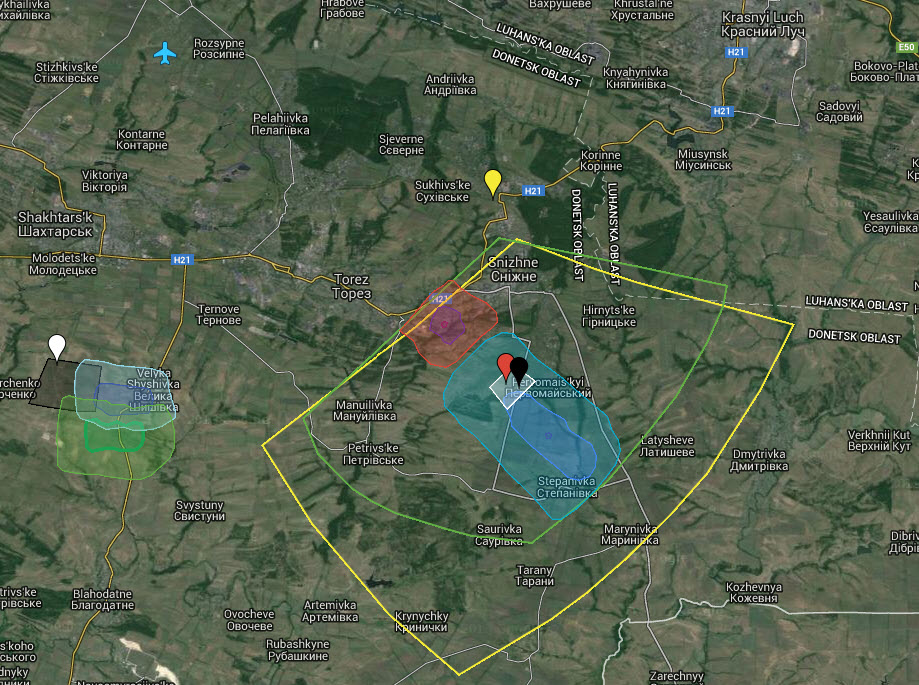

Another key concern for Russia was the inclusion in the report of the results of a trajectory simulation conducted by Almaz-Antey at the request of the DSB. This computation, which used, as a starting point, the explosion location and impact dispersion data compiled by NLR, reverse-projected a ballistic trajectory to an identical launch site as the simulations ran by the 3 other parties engaged by the DSB – all inside a separatist-held polygon south of the village of Snizhne. Almaz-Antey presented this trajectory simulation during the second progress meeting in early May. At this point in time (before seeing the definite conclusions in the draft report), it appears that the Russian side was less concerned with presenting this “counterfactual” scenario, as it still insisted on its main hypothesis, i.e. a different angle of approach, a different Buk type, and a different launch location.

However, due to its subsequent change of position and its own request to remove the original Almaz-Antey presentation from the report, Russia was left in the awkward position to have a final report with only one reference to an Almaz-Antey trajectory simulation: one pointing a finger at separatist-held territory. This was the reason Russia requested the DSB to remove the reference to the second simulation by Almaz-Antey, calling it “based on false assumptions about the location of the detonation and the weapon type.”

The DSB, however, declined Russia’s request to remove this reference.

Russia’s attempts to substantiate a missile trajectory leading to Zaroshchenske (approx. 20 km to the west of the polygon, computed by the 4 other simulations) was essential to the official Russian narrative. Four days after MH17 was shot down, the Russian Defence Ministry published satellite imagery, allegedly taken on the day of the crash, which purported to show two Buk units in the immediate vicinity of Zaroshchenske. The authenticity of the imagery has been disputed both by Ukraine and by Bellingcat, among others. Furthermore, Novaya Gazeta interviewed residents of the village of Zaroshchenske (currently – and at the time of the interviews – under separatist control), who confirmed that there had been no Ukrainian military presence in or around the village at any time after May 2014. (On June 8th I spoke with several Zaroshchenske residents by phone as well, they told me the same thing). Cartography experts interviewed by Novaya Gazeta alleged that Zaroshchenske, at the time of the crash, was “6-7 km within rebel territory” None of the interviewees had seen or heard anything resembling a missile launch on July 17th. Yet, keeping consistent with its early narrative, Russia has insisted that the only conceivable trajectory of a Buk might have come from a narrow square near that village.

The missing radar data

In keeping with its non-deterministic strategy, as of the third progress meeting Russia re-introduced the “air-to-air” missile hypothesis. This hypothesis had been first introduced during the Russian Defence Ministry press conference on July 21st, 2014, when Russia declared it had radar data proving that a Ukrainian SU-25 fighter had been flying up towards the altitude of the MH17 airliner at 16:20 local time.

“Russian system of air control detected the Ukrainian Air Force aircraft, purposed Su-25, moving upwards toward to the Malaysian Boeing-777. The distance between aircrafts was 3-5 kilometers.”

Russia claimed that the alleged Su-25 flew without active radio self-identification (a switched-off transponder), thus it could be registered only by Russia’s primary, active scanning radar system. At the July 21st, 2014 press-conference, the Russian Defence Ministry displayed a video recording of a radar screen, purported to show the Ukrainian fighter.

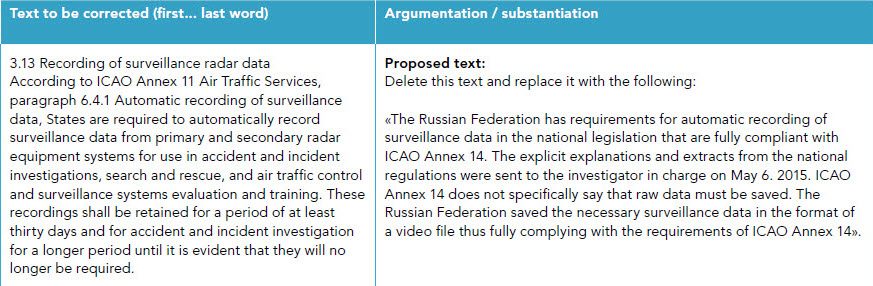

From the DSB final report, it becomes evident that when Russia re-introduced the air-to-air hypothesis, it no longer referred to the alleged observed presence of a Ukrainian fighter near the Malaysian Air Boeing. Furthermore, Russia declined to provide the raw data from its radar locator sites near the Ukraine border to the DSB. Russia’s argument was that international requirements under ICAO aviation rules did not specify what type of radar data it is obligated to keep for 30 days, and that its presentation of a video screen recording of the radar satisfies such legal requirement. This refusal forced DSB to inquire with ICAO, which confirmed that, to the contrary of Russia’s claim, all raw data must be preserved for a period of 30 days [the alternative interpretation is untenable, as no authentication of a video screen recording can be performed].

During the second progress meeting in May 2015, the Russian delegation announced that the raw radar data was no longer available. Russia said it had “not saved this information, because it was not obliged to do so since the crash had not taken place on Russian territory.” From this point onward, Russia no longer referred to a particular, observed Ukrainian plane near the Boeing, but to the hypothetical scenario that there may have been a plane, and it might have shot an unspecified air-to-air missile with a similar (also unspecified) shrapnel payload.

A multi-variant truth

Russia’s extensive, and often fluctuating, inputs to the Dutch Safety Board may appear haphazard and stochastic – the natural artifact of a system not used to structured, deterministic processes. Or it may be the actual strategy: one of deferral of the truth through obfuscation. Truth, it appears throughout the Russian inputs to the DSB report, is too complex to be known. MH17 may or may not have been hit by a ground-to-air missile, but it may have well been an unknown other type of an air-to-air missile. And even if it were a Buk, from the evidence at hand, it is impossible to ever ascertain the specific type of Buk that may have been used. The launch site, too, may have been under Ukrainian or under separatists control.

This position is more reminiscent of a criminal defense lawyer’s strategy than of a proactive participant in an investigation – one which, this very participant claims, has taken too long to complete. At the same time, it consistent with the sincere response that Almaz-Antey’s CEO Jan Novikov gave to a Chilean reporter during a press conference several hours before the presentation of the DSB report.

“Why does Russia’s hypothesis always change?” asked the reporter. Novikov replied:

“Russia’s position has always been one of retaining multi-versionality of scenarios, until the very end, when we can choose namely that scenario, which….which actually happened”

___________

Footnotes:

[1] It is not clear whether the original reference was in the context of the undisputed Russian involvement in the Crimean events, or it made an explicit assumption for involvement in the Donbass conflict]

[2] “About the Investigation”, page 9, par. 5, http://cdn.onderzoeksraad.nl/documents/report-mh17-abouttheinvestigation-en.pdf