Wilayat Internet: ISIS’ Resilience across the Internet and Social Media

Laurence Bindner, Raphael Gluck

This article was originally published in French on Ultima Ratio.

Since partly going underground in the deep-web, ISIS exerts continuous pressure to make its propaganda surface on the public web. Adapting constantly to ever more active censorship, ISIS uses the various web platforms in an opportunistic and agile way. Therefore, online counter-terrorism bodies must have a holistic and rounded approach, take global action that encompasses newer social-media platforms to identify and target, in priority, dissemination streams of jihadist contents.

Message propagation is a key component of terrorist or insurgent groups’ strategy, whether their battle is political, ideological or religious. The systematic dissemination of the message is crucial to rallying people to their cause, announcing of an action or justifying it, all for the purposes entrenching and developing their influence, and amplifying the impact of their operations or terror attacks, in particular offering them a psychological echo among target populations.

Jihadist groups like ISIS or al-Qaeda have integrated this media imperative by closely linking propaganda and leadership, thus embedding the media branch in the heart of the operational apparatus. The martial lexical field shows it: media propaganda is a war front per se. Beyond the sole aspect of ideological propaganda, leveraging it in an operational purpose is at stake, at each stage of a potential terror attack supply chain (recruiting, fundraising, circulating lists of targets, providing tutorials, remote-controlled operations, making claims, and even live broadcasting an attack with go-pro cameras). As the military setbacks have accumulated in Iraq and Syria, the virtal front has taken on vital significance, as the locus of virtual expression of the Caliphate’s ideology, that has to remain vivid until its concrete resurgence, and as an operational and logistic tool. The group has mastered not only the virtual world but has done so in multiple languages to reach the largest audience and ISIS channels proliferate in over 25 different languages increasing every day.

Screengrab 1: Examples of the martial lexical field of pictures broadcast on Telegram and other social media – “media war,” “front lines,” “tour of duty,” “repelling assaults.”

One of ISIS’ main characteristics is found in its structure, the production scale and the modus operandi of its media enterprise, in particular its tactics to systematically leverage social networks and the various accessible webtools, harnessing their momentum since the end of the 2000s. Emerging from obscure web forums (mostly in Arabic and difficult to access) towards the surface web contributed to a popularized and “available” jihad. This momentum was somewhat curbed at end of 2015 when numerous accounts and user profiles (in particular on Twitter) were suppressed in the wake of the Paris attacks and the first victims families’ lawsuits in the fight against terrorist propaganda. ISIS subsequently migrated towards Telegram, an encrypted messaging application, choosing operational security and longevity over its communication reach and visibility.

ISIS’ migration to apps like Telegram was a ‘tactical retreat’ of sorts to partially operate underground in the deep web. Indeed, during the early months of ISIS on Telegram, channels and groups were mostly accessible via public channels found by searching relevant keywords (such as #KhilafahNews) but many of their channels have quickly evolved into key-only access (a link key available for a very short period of time that gains access to a particular channel). Telegram thus remains a relatively safe haven for ISIS: channel and group deletions occur less frequently than in mainstream social media and the unidirectional format of the channels (where only designated moderators can post) doesn’t give room to counter propaganda. Last but not least, contents (documents, videos, pictures, audios, etc) can be directly uploaded inside the application, without links towards other websites, without limit of size, giving the content greater shelf life and a far lesser rate of deletion than in mainstream social media such as YouTube, Facebook and Twitter.

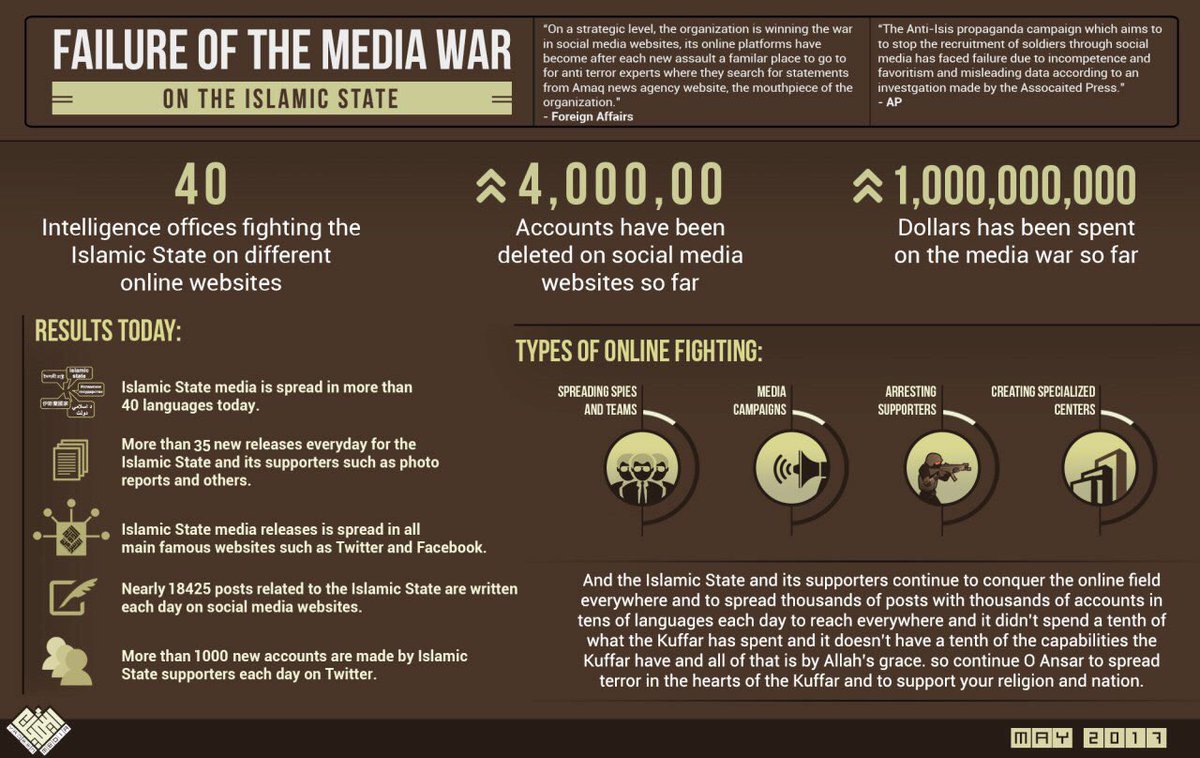

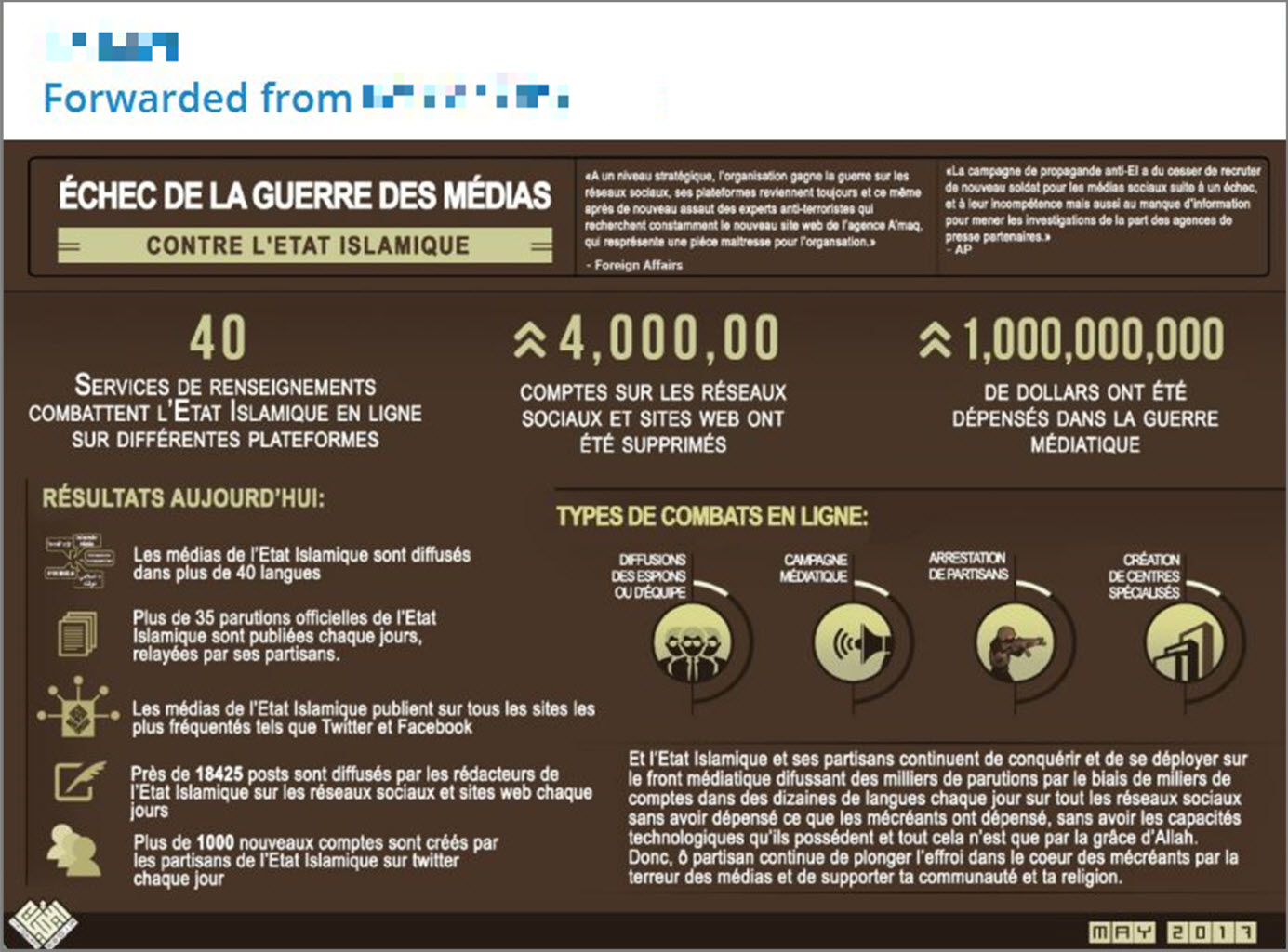

Screengrab 2: Failure of CT media war – infographic broadcast on a Francophone ISIS-linked Telegram channel (May 2017)

Telegram: a secure “support system”

Because of its enduring presence on Telegram, ISIS is also using the application to propel its message to other platforms and social media. To this end, ISIS conducts two types of operations: launching “salvoes” of links pointing towards a large range of platforms in order to circulate specific content, whilst in the background, a low-intensity activity of incursions into mainstream social networks. Last, a relay race operates between the various networks as well as within each one, to maintain an “always on” presence of its content and accounts.

The surfacing and dissemination of jihadist messages on the public web serves two purposes. Apart from the retention of a steady virtual presence from which ISIS can connect with its loyal fanbase (which allows ISIS to boast about online CT failure, see screengrab n. 2), the aim is also to infuse the message into social networks. The recruitment reach is expanded to a larger public audience than Telegram users: more accessible on Twitter, Facebook and Google+ to potential recruits, these accounts may be providing a (first) interaction with jihadis or contact with propaganda. Ideally, the subject is then funneled to Telegram where the exposure to this propaganda turns out to be more intense.

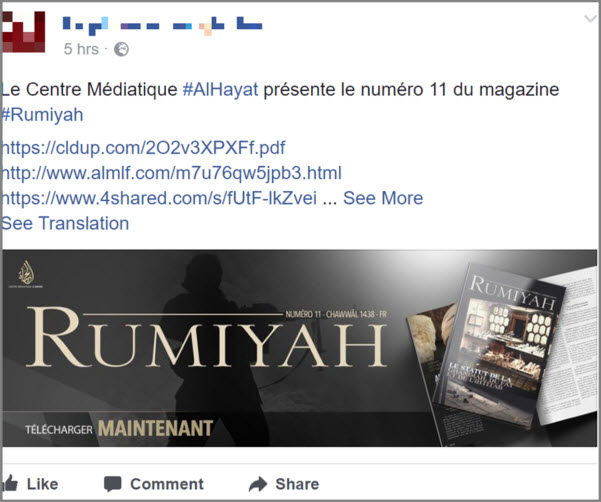

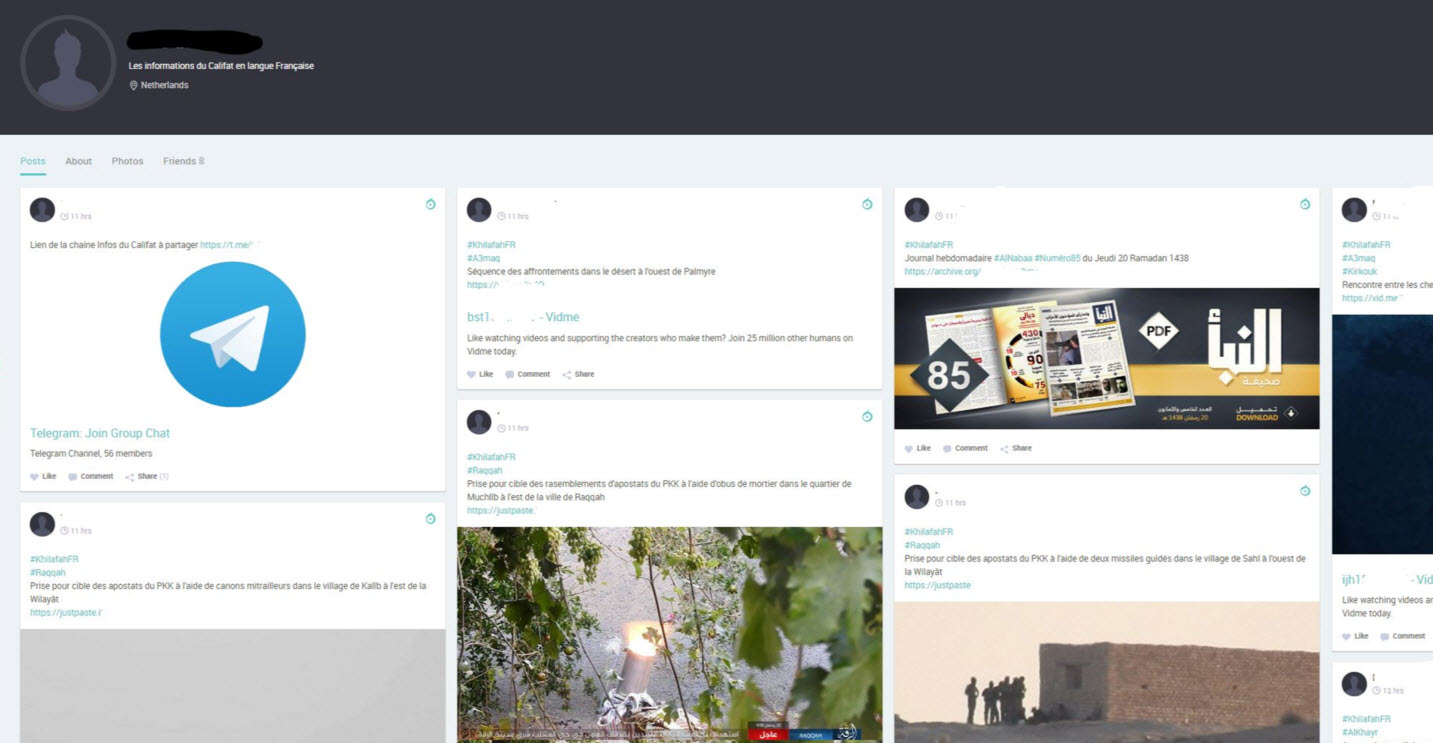

The launch of an official publication by one of ISIS’ media outlets systematically comes with a barrage of links pointing towards files on cloud servers or storage websites, disseminating as much as possible and even renewing them once the first salvoe of links are censored and removed by the interested parties. This process is repeated frequently over the next months. Spreading risk of censorship and overwhelming cyber intelligence teams are two of the pursued objectives here. These links are immediately shared on social networks and become available to groups, followers, friends or publicly with hashtag searches, reaching an important recruitment pool by capillarity (screengrabs 3 and 4)

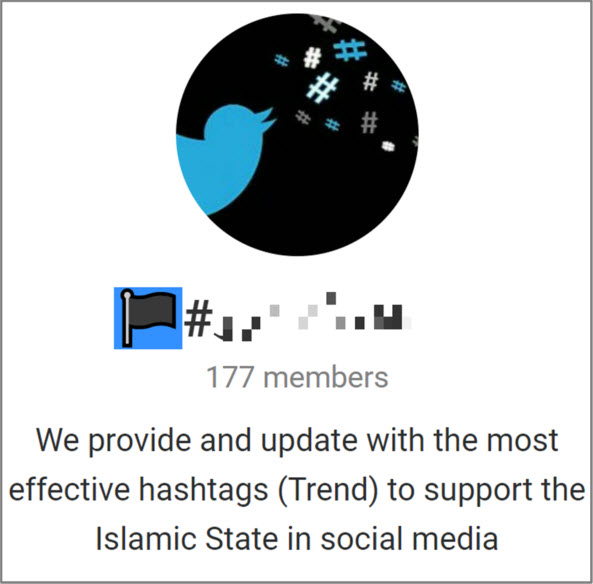

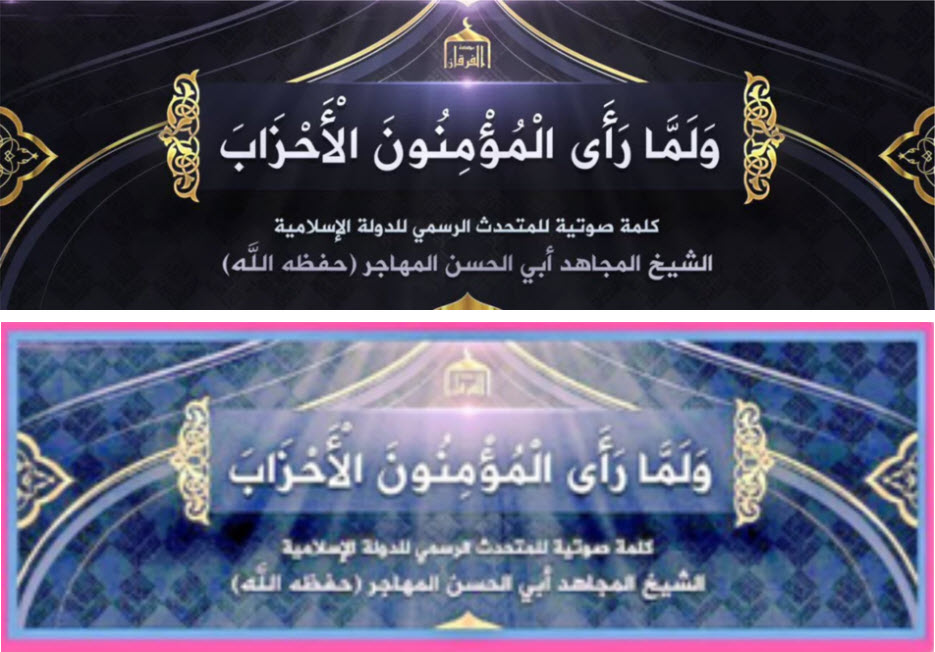

The use of hashtags, popular across social media can be viewed as batons in a relay race passed between platforms or within multiple consecutive accounts on a single platform. They can be correlated with ISIS, but recommendations of unrelated but trending hashtags are being regularly circulated by ISIS-linked accounts or channels, to disseminate to a wider audience (screengrab 5). These links appear systematically with each official ISIS publication, whether video, audio or a new magazine. Techniques of lingering or reappearing on cloud server or storage sites are numerous. On occasion images or text can be altered to bypass detection by algorithms of digital fingerprints (screengrab n. 6).

Screengrab 5: ISIS-linked Telegram channel providing most trending hashtags per country on a daily basis to disseminate propaganda (July 2017)

Screengrab 6: Example of a possible picture alteration to bypass detection by algorithms of digital fingerprints – Teaser image of ISIS’ spokesman audio release (12 June 2017)

A relay race between platforms

Alongside these salvoes, constant incursions to the regular internet involving tactics to bypass basic censorship is taking place on a daily basis, by way of a relay system between groups, accounts, channels and social media. Such a relay system can exist between several platforms or within a specific one. There are numerous examples, some of the more prominent ones are described below.

Just as an individual or a company may open multiple accounts across different platforms in social media, ISIS-linked groups or sympathizers maintain their presence on multiple platforms. Media outlets like Amaq, Nashir, and French language media division An-Nur diversify their risk of censorship and increase their resurgence capabilities by maintaining a presence on Telegram, Facebook, Google +, WhatsApp, etc. When an account in censored or closed down in one network, followers can revert to the alternative accounts on a different platform where a new link to the original network will eventually be relayed. Additionally, dormant “back-up” accounts are sometimes silently posted to the original network, springing to life once the initial account is deleted.

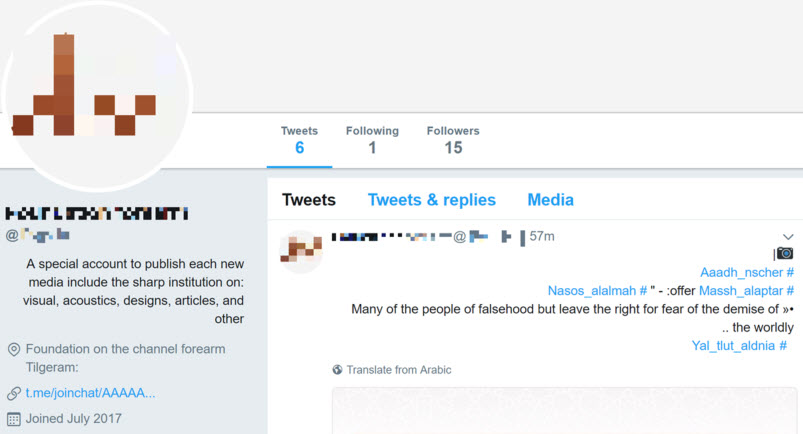

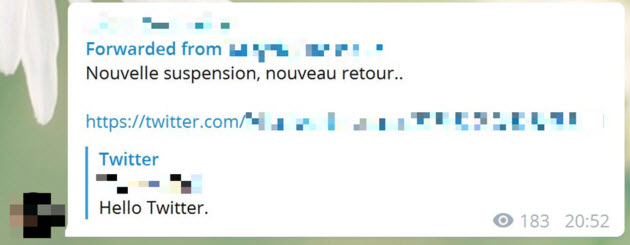

Links to new Twitter accounts, or “resurgent accounts” for old ones after deletion are frequently promoted via Telegram. These new accounts with sometimes innocuous or randomly generated profiles or usernames succeed (despite a limited time frame) to circulate current ISIS content and on occasion to list a new “exclusive” Telegram channel in the bio, at times a key that doesn’t not appear elsewhere (screengrab 7). Turnkey tweets may be provided by Telegram so that sympathizers just have to copy-paste them on Twitter.

The same resurgence process also appears on Facebook with slower censorship up until now, providing further opportunities to chat and share links or contents.

Screengrab 8: Announcement of the return of a previously suspended account on Twitter via Telegram (June 2017): “Once again suspended, once again back — Hello Twitter”

In order to minimize the risk of deletion, we have observed referrals from one Telegram channel to a third-party network explicitly with the aim of obtaining a link towards a new channel. ISIS media outlets have thus preceeded on several occasions, referring to their Google+ group to get first notice of its next Telegram channel key.

It should be noted that their penetration into social networks goes beyond the aforementioned platforms. ISIS regularly sets up shop with Instagram, Snapchat, and emerging new apps. Recently, the new social media startup Baaz endured significant infiltration by ISIS sympathizers who stepped into the control breaches of a small and still inexperienced team, by creating public accounts and groups en masse (screengrab n.9).

Branding and resurgence

Within a single platform, ISIS deploys several methods to relay channels or accounts at risk of being censored.

In Telegram, channels are created in advance of their ‘deployment’ or activation date. Clones of existing channels or anonymous ones are created as backup and later renamed. The first key links may only last several hours to limit infiltration by intel services, researchers, journalists, requiring cyber-intelligence teams to maintain a near constant watch to keep pace. Some channels, known for their credibility, attract a large audience due to branding recognition (for instance the acronym of the channel’s name, or an iconic logo) even before the release of the channel’s first message.

Screengrab 10: Announcement that a relay link to Telegram channel will be provided via Google+ (July 2017): “in case of censorship of our Telegram channel, new links will be posted [on our Google+ group] incha Allah”

Screengrab 11: Example of the short life expectancy of a key link on Telegram to limit infiltration (June 2017)

Similar branding phenomenon takes place on Facebook where an evidently ISIS-linked account includes a similar looking “duplicate” account as a “friend” often with an identical or similar profile picture, name or bio, relaying the duplicate account ahead of the former’s removal. Dozens of twin profiles have been identified in the past few months, with a life expectancy of several days each. Branding is crucial and permits immediate recognition of the new account.

Conclusion: A holistic and inclusive approach is necessary

Despite an increased alertness of authorities and social network companies, ISIS has shown a significant resilience due to its flexibility, its modular approach and adaptability towards online removal of jihadist content. It has succeeded in maintaining constant distribution of its propaganda to reach its recruitment pool and beyond. Additionally, its broadcasting entails a form of normalization of extreme violence, increasing our tolerance of “acceptable levels of violence”. Indeed, certain audio and video messages from rival jihadist groups like al-Qaeda that equally incite jihad or committing terror attacks, but lacking perhaps in extreme graphic content, have remained online for several months, being considered as less dangerous than those of ISIS.

The targeting of this distribution must remain one of the priorities of counter-terrorism authorities and social media companies, whose holistic approach is crucial: the thorough understanding of flows, relays, exchanges, rebounds and bridges between platforms and within platforms will allow for an improvement of this targeting. It will also allow the relevant authorities to more easily identify the nodes, breaches and relevant rooms to inject counter or alter-narratives, or redirect tools. In addition, CT teams must follow these flows constantly to keep pace of the most recent accounts, releases and channels. Last but not least, the joint collaboration of main social networks has to extend to smaller and younger players, often less equipped technologically, legally and financially, and overwhelmed by the mass of jihadist content invading their platforms, as recently underlined by Mariusz Zurawek, founder of Justpaste.it.

If global action is not undertaken in the near future, we are at risk of witnessing – in addition to the survival and expansion of the jihadist message – a surge in the use of content aimed at operational use. This is evidenced by the recent cases of Khalid Masood (Westminster attack – 6 dead, 44 wounded) and of Salman Abedi (Manchester Arena – 22 dead, 116 wounded), both of whom had previously watched or downloaded manuals or tutorial via social media.

Laurence Bindner is the former Director of Development of the Center for the Analysis of Terrorism (CAT) in Paris. Her work covers analysis in terrorism financing (see ISIS financing), the links between terrorism financing and illicit trade and the quantification of jihadist networks in France and the EU. She developed an expertise on jihadist rhetoric online.

Raphael Gluck is an independent researcher and analyst focusing on the spread of terrorism online via the web, social media and the deep and dark web. His findings have been reported in dozens of media outlets and he is frequently consulted by experts at think tanks and governments’ organizations. He can be found on Twitter at @einfal.