From Crimea to Iran: Two More Ships Join Russia’s Grain-Smuggling Fleet

You can read the version of this article published on Lloyd’s List here.

Last year Bellingcat revealed that Russian ships were making calls to the Port of Sevastopol in Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, transporting grain from other occupied parts of the country. The quantity of grain exported from occupied Crimea has reportedly massively increased since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and its seizure of Ukrainian territory.

Ships involved in the scheme are violating international maritime guidelines by turning off location trackers in an attempt to hide their whereabouts — an act known as ‘going dark’. As previously reported by Bellingcat, two ships, the Mikhail Nenashev and Matros Shevchenko, sailed from Sevastopol directly to Iran.

Bellingcat can now reveal that in recent months, the bulk cargo ships Zafar and Zaid have also joined the grain-plundering fleet, sailing under the Russian flag.

These ships are operated by a different company, but they serve a similar route — they transport grain from the Russian-occupied port of Sevastopol and export it through the Bosphorus and beyond.

The Zafar and Zaid were observed making the trip from Sevastopol to Iran last year and to Syria this year. Since last year they have been operated by the Astrakhan-based Salmi Shipmanagement.

Some of these previously unreported voyages could be seen through open sources. Bellingcat has obtained satellite images showing the Zafar and the Zaid docked at a grain terminal in Sevastopol and several weeks later docked at Bandar-e Emam Khomeini, a major port in Iran on the Persian Gulf. AIS data provided by Lloyd’s List Intelligence allowed us to monitor the position of the vessels on their voyages to Iran, allowing us to obtain photographs of both vessels passing the Bosphorus fully laden. Data from Lloyd’s List on the change of the ships’ draught indicates that they unloaded cargo at the Iranian port. This is the same route taken by the Mikhail Nenashev and Matros Shevchenko in July 2023.

Bellingcat also used satellite images to establish that the Zafar docked at the same Sevastopol grain terminal in January and February this year. These images, as well as AIS data, appear to corroborate elements of Russian state documents published by a Ukrainian website which claims that both ships have also exported grain to Syria.

These revelations come at a time of enhanced scrutiny towards Moscow’s relationship with Tehran. Bellingcat also discovered that a senior figure at the stevedoring company of this Sevastopol terminal has made visits to Iran where he met state officials involved in transport.

On March 29, Ukraine’s Prosecutor for Crimea announced that the captains of the Zafar and Mikhail Nenashev were wanted by Ukraine on suspicion of illegal exit from and entry to Ukraine, referring to their voyages from the occupied peninsula. On April 24 the prosecutor announced that the captain of the Zaid was wanted on suspicion of the same crime.

The Zafar Sets Sail for Iran

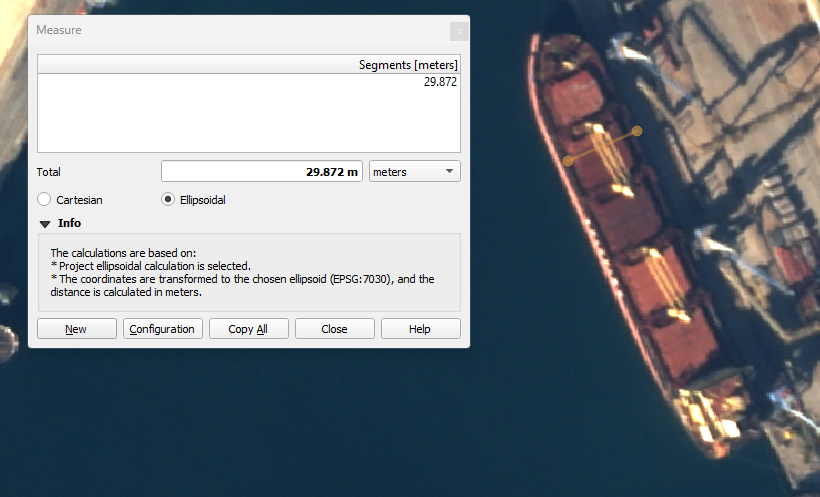

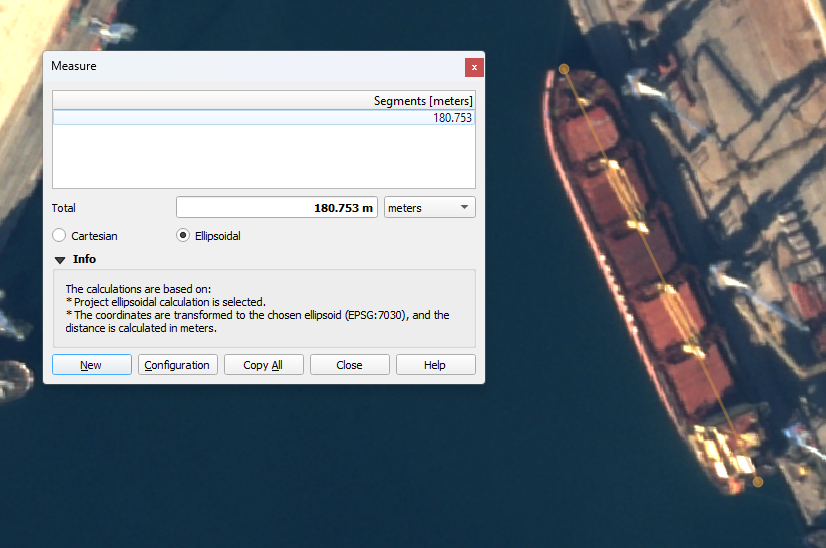

The Zafar, a 37,300 deadweight ton (DWT) bulker, has a few recognisable features. According to websites such as VesselFinder and SeaSearcher, it is 180 metres long and 30 metres wide.

The Zafar is distinguished from the Zaid by its four cranes, as well as its accommodation block with the bridge. All of these are of a faint yellow colour. Both features are easily spotted in satellite images.

Bellingcat used open sources to tracked the Zafar’s clandestine voyage to Iran last October. Here’s what we found.

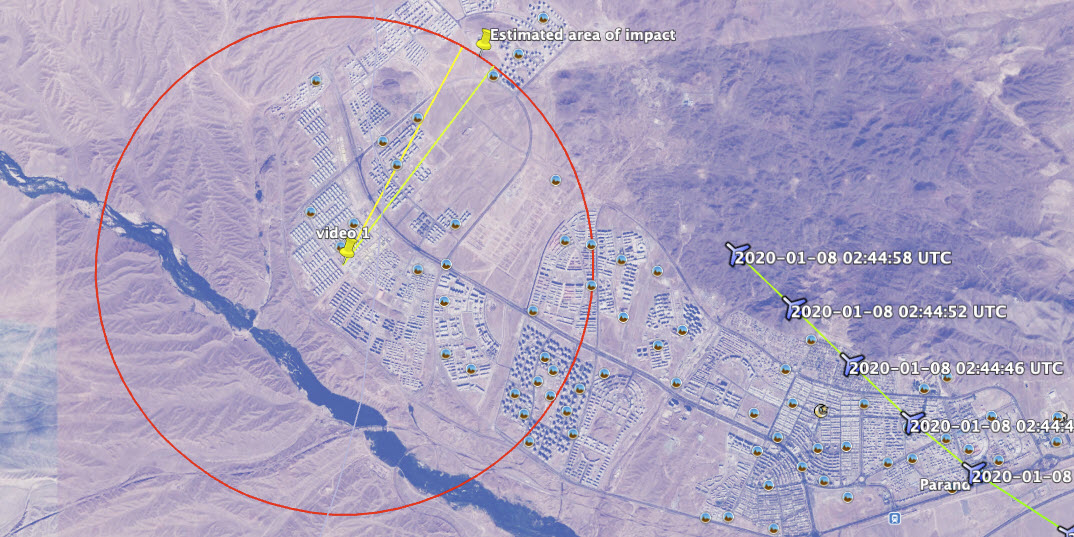

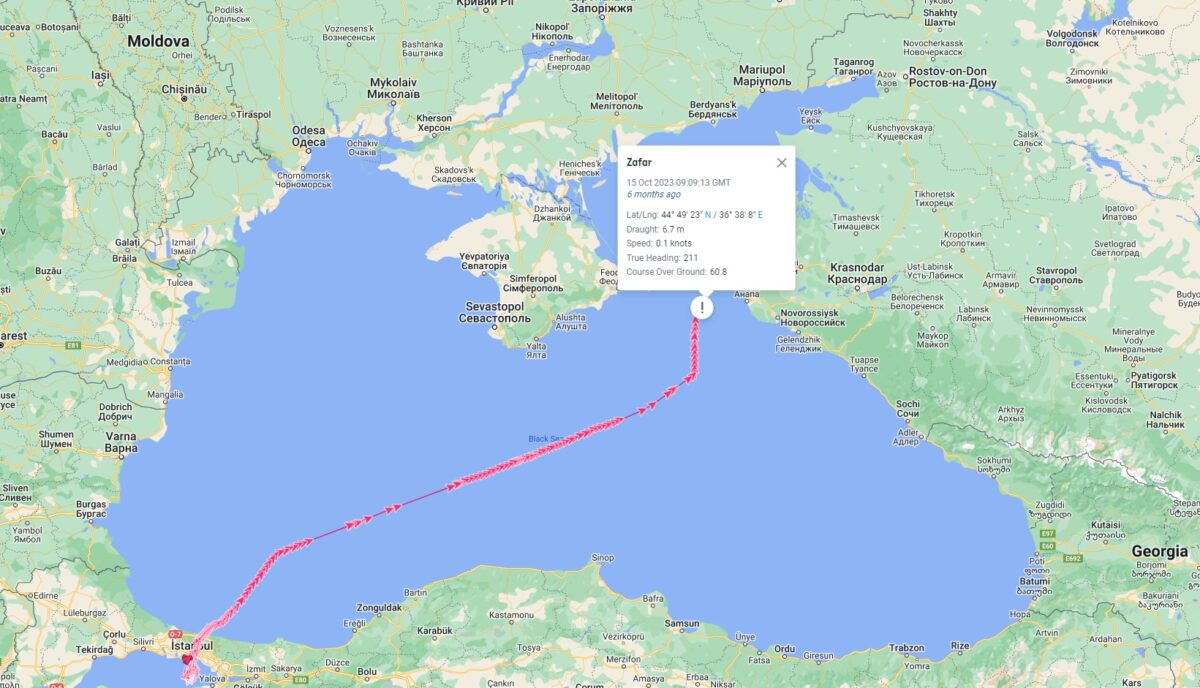

As is common for vessels involved in Russia’s grain plundering operation, the Zafar ‘went dark’ in the Black Sea on October 15 after transiting the Bosphorus on October 13. Going dark is a maritime industry term used for vessels that deliberately hide their whereabouts by turning off Automated Identification Systems (AIS), in violation of the International Maritime Organisation’s best practices guidance.

Automated Identification Systems (AIS) provide open source information on the positioning and movement of ships. The deliberate disabling of AIS without legitimate cause is considered a deceptive shipping practice.

The Zafar transmitted a signal on October 15, 2023 at the coordinates (44.82294333, 36.63565333) on its approach to the Kerch Strait, which connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Azov.

As previously reported by Bellingcat, the Kerch Strait has played a role in maritime grain plundering as the site of ship-to-ship transfers during which smaller ships sail to open seas to transfer cargo to bigger vessels.

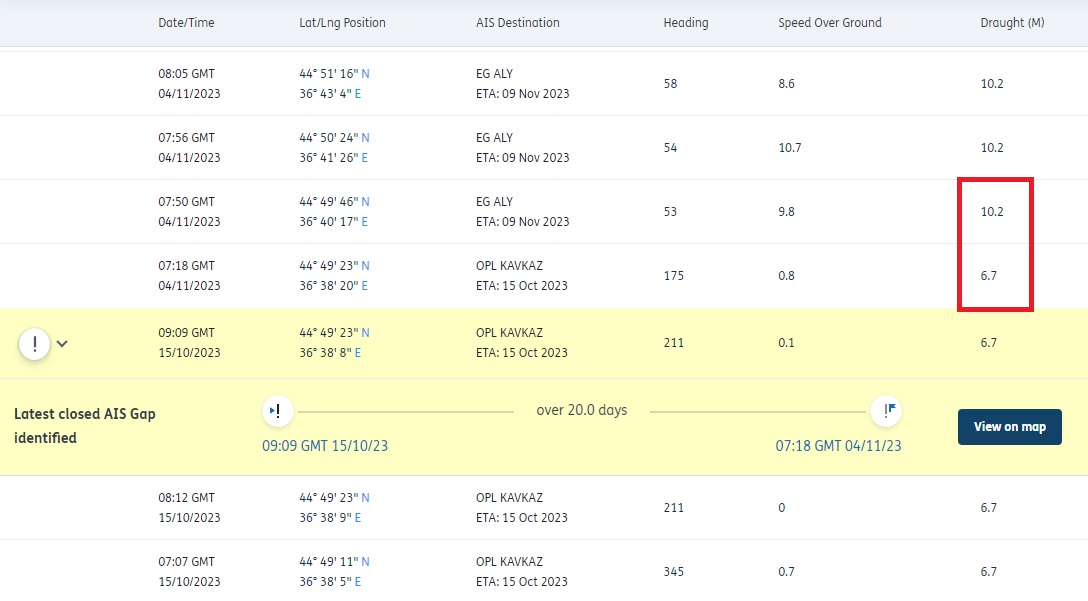

The screenshot below from Lloyd’s List Intelligence platform SeaSearcher shows the ‘AIS GAP’ — the point at which the Zafar stopped transmitting its coordinates.

Although it had turned off its AIS system, open sources can tell us about Zafar’s next movements. On October 17, a ship with the same dimensions, features and colour as the Zafar appeared at Sevastopol’s Avlita Grain Terminal – about a day’s sailing time from the Kerch Strait. This is the same terminal at which Bellingcat found that the Mikhail Nenashev had loaded grain in June 2023.

The ship seen in this satellite imagery is distinctive. Note its yellow cranes and the shape of its bridge, which all match those seen in photographs of the Zafar.

Furthermore, the angling of the satellite imagery means that markings are visible on the hull of the vessel. While the word itself is not fully legible, we can count eight letters on the hull — the same number as in the word ‘shipping’, seen in higher-resolution photos of the Zafar.

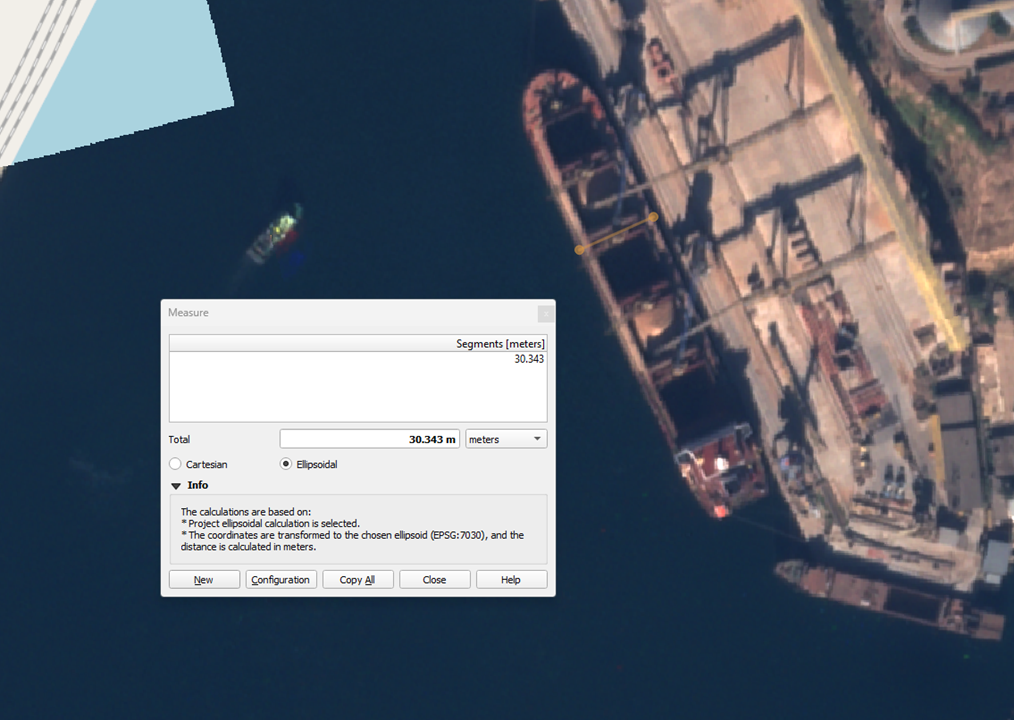

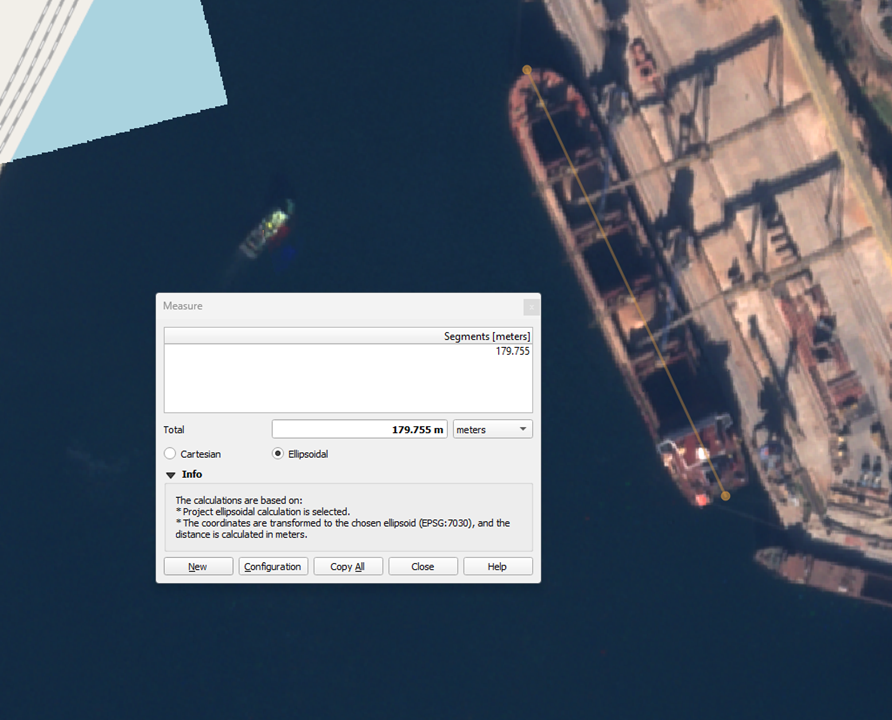

By using QGIS software, we can measure the the dimensions of the vessel in the satellite imagery. It is 180 metres long and 30 metres wide — just like the Zafar.

Multiple images of the vessel uploaded to MarineTraffic show that the Zafar’s hull is painted red below the waterline. Fortunately, the angling of the satellite which took this photograph allows us to see that this red paint on its hull is above the waterline.

This indicates that the Zafar had not yet been fully loaded with cargo when the image was taken.

Two days later, the ship’s hatches opened. Satellite imagery taken on October 19 shows that the Zafar was being loaded with a substance matching the colour of grain.

The Zafar had its AIS transponder off for 20 days (from October 15 to November 4). Lloyd’s List Intelligence data shows the ship’s draught was 6.7 metres prior to its Sevastopol port call.

The draught is the vertical distance from the waterline to the baseline; a change in the draught generally means a change in the ship’s weight and cargo. According to Lloyd’s List, as draught data is a manual input done aboard a ship it is not always a reliable source of information. However, there are certain instances where draught data must be accurate for safety reasons, such as passing through major chokepoints. Therefore, it can be used as supporting evidence when drawing conclusions in conjunction with other information — such as the depth of the hull in our photographs of these vessels transiting through the Bosphorus.

New draught information appears to have been inputted during the Zafar’s stay at the Avlita terminal.

When the ship resumed transmitting its coordinates (at 44.88906333, 36.79853333) after visiting Sevastopol, its draught was at 10.2 metres. This suggests that the ship was loaded with a significant quantity of cargo.

On November 11 it headed south and transited the Bosphorus strait, where it was photographed fully laden by co-author Yörük Işık.

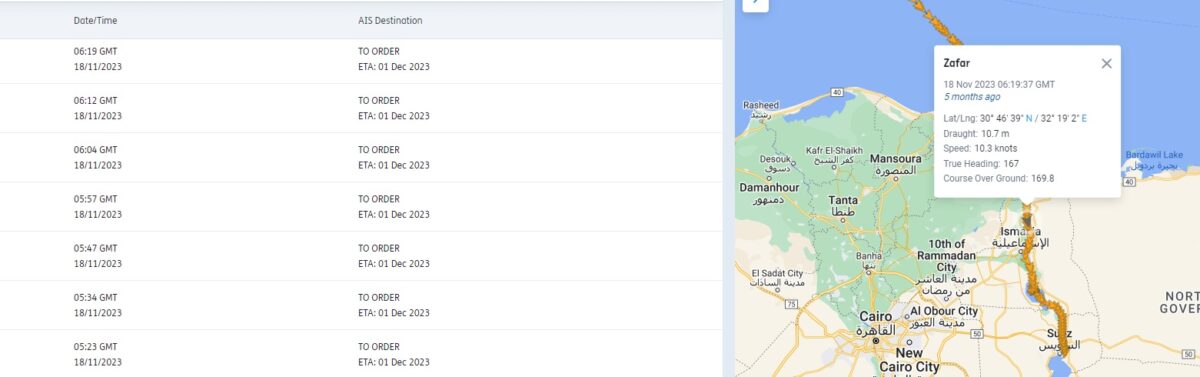

According to AIS data obtained from Lloyd’s List Intelligence, the Zafar transited the Suez Canal on November 18 towards the Red Sea. At the time it was using the destination field within the AIS data to indicate “TO ORDER”, rather than stating a next port of call.

The Zafar anchored off the coast of Iran in early December. On December 12, it finally docked at the Bandar-e Emam Khomeini terminal. AIS data shows that the Zafar was docked at 30.43933333, 49.04966.

In the immediate vicinity there was only one ship with the same dimensions. The other features, such as the yellow cranes, also stand out.

Data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence shows that the ship’s draught dropped considerably from 10.7 metres to 6.7 before it left on December 18. As the maximum draught of the Zafar is 10.67 metres, this suggests that the ship was operating at full capacity and had unloaded a large quantity of the substance seen in the satellite images from Sevastopol.

The Zaid Heads to Iran

The Zaid, a 37,349 DWT bulker, made the same trip just a few weeks before the Zafar. According to VesselFinder, the Zaid and the Zafar’s dimensions are virtually the same (180/30 metres).

The main visible difference between the two ships, at least currently, is the colour of their cabins. Where the Zafar’s cabin is yellow (except for the lower part of the cabin), just like its cranes, the Zaid’s cabin is almost completely white.

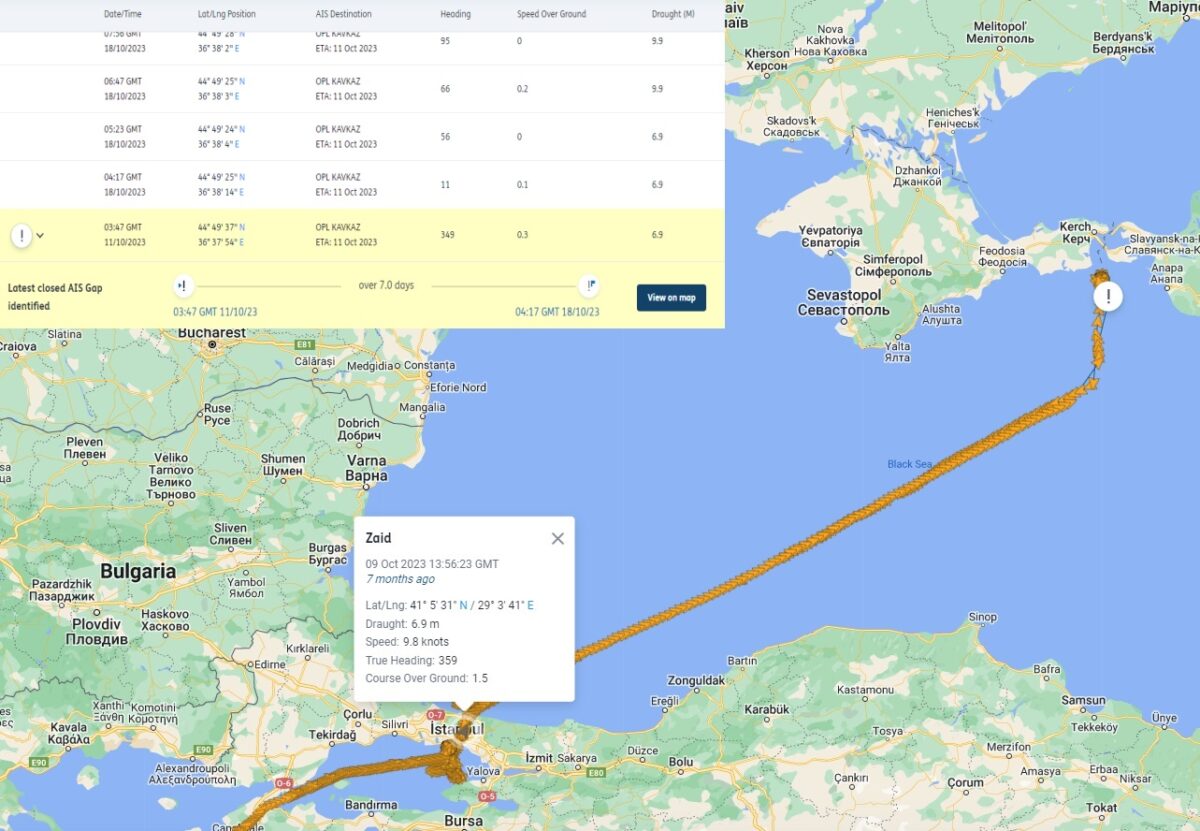

On October 9, 2023, the Zaid transited the Bosphorus in Istanbul, sailing onto the Black Sea. The ship then travelled to an area near the Kerch Strait and its AIS ‘went dark’ after October 11.

On October 13, Planet Labs satellite images captured the ship at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol.

Let’s take a closer look at this satellite image.

In the GIF image below, the yellow boxes highlight the Zaid’s four yellow cranes, the blue boxes its cargo compartments, the orange its the antenna and the red the chimney.

Later, the magnifications shown in the circles to the left highlight the brown substance being loaded into the cargo compartment.

We can compare all these features to a photo of the Zaid taken by co-author Yörük Işık on October 30, 2023. The cranes are shown in the yellow boxes. The blue arrows show the cargo compartments. The orange box shows the antenna and the red box shows the chimney.

For further verification we can again measure the ship using QGIS. The dimensions match those of the Zaid — 180 metres long and 30 metres wide.

By October 14, Planet satellite imagery showed that the remaining compartments had been filled with the same substance.

The ship began transmitting AIS positions again on October 18 near the Kerch Strait (44.82354333, 36.63712667), according to Lloyd’s List Intelligence data shown in the map earlier in this section.

On October 30, Yörük Işık photographed the Zaid transiting the Bosphorus, this time headed in the direction of the Mediterranean.

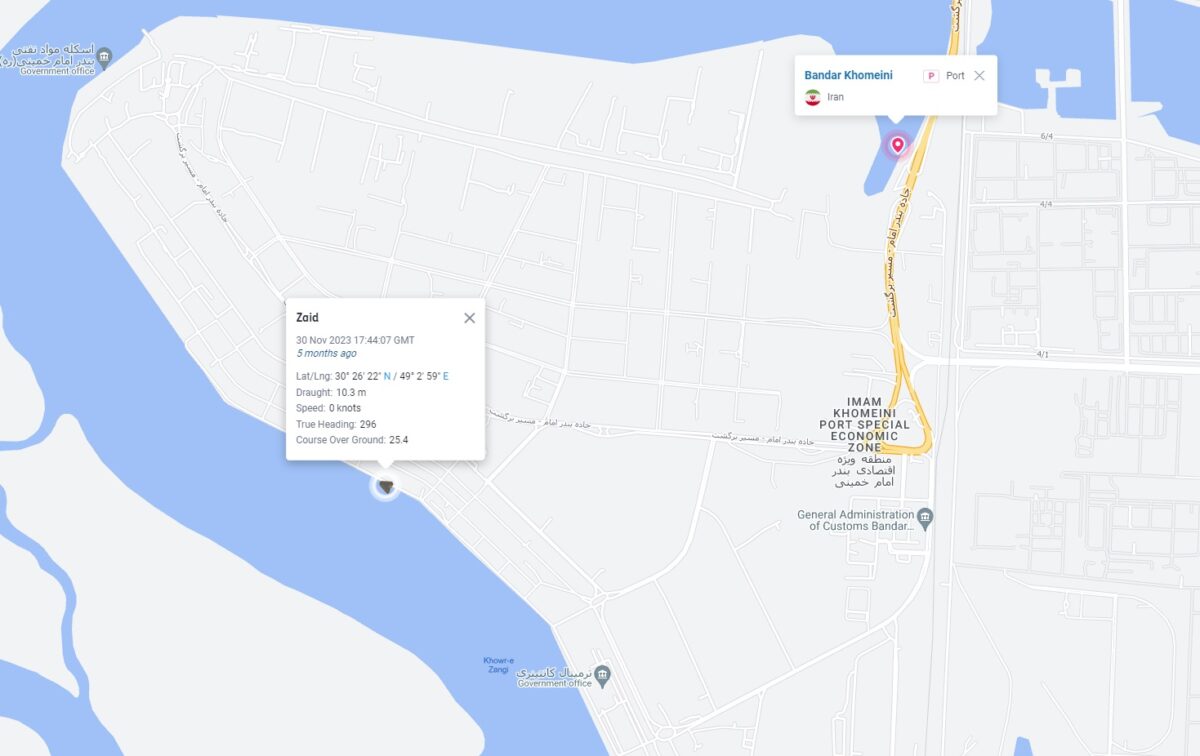

It would take until November 28 for the ship to berth at the dock in Bandar-e Emam Khomeini, where AIS data shows that it stopped at 11:30 am UTC.

Although commercial satellites did capture this area on the same day, they did so prior to the Zaid’s arrival.

Bellingcat was unable to obtain satellite imagery of the port on November 29, but on November 30 AIS data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence shows that the Zaid was docked at 30.43954333, 49.04959333 in front of a row of warehouses in Bandar-e Emam Khomeini. This is approximately same location where the Zafar was moored.

On December 2, the ship’s draught went from 10.3 metres to 6.6 metres according to Lloyd’s List Intelligence data, suggesting it unloaded a considerable amount of cargo.

According to Lloyd’s List data, the ship stayed in the same position until December 3 when it then re-berthed towards the northwest and then departed the port on December 4.

There are no bills of lading (i.e. documents acknowledging the receipt of cargo for transportation) for the Zaid’s and Zafar’s shipments to Bandar-e Emam Khomeini.

These would be needed to establish the sender and the receiver of the shipments and to ascertain the type of cargo that was transported with more certainty.

Owners and Operators

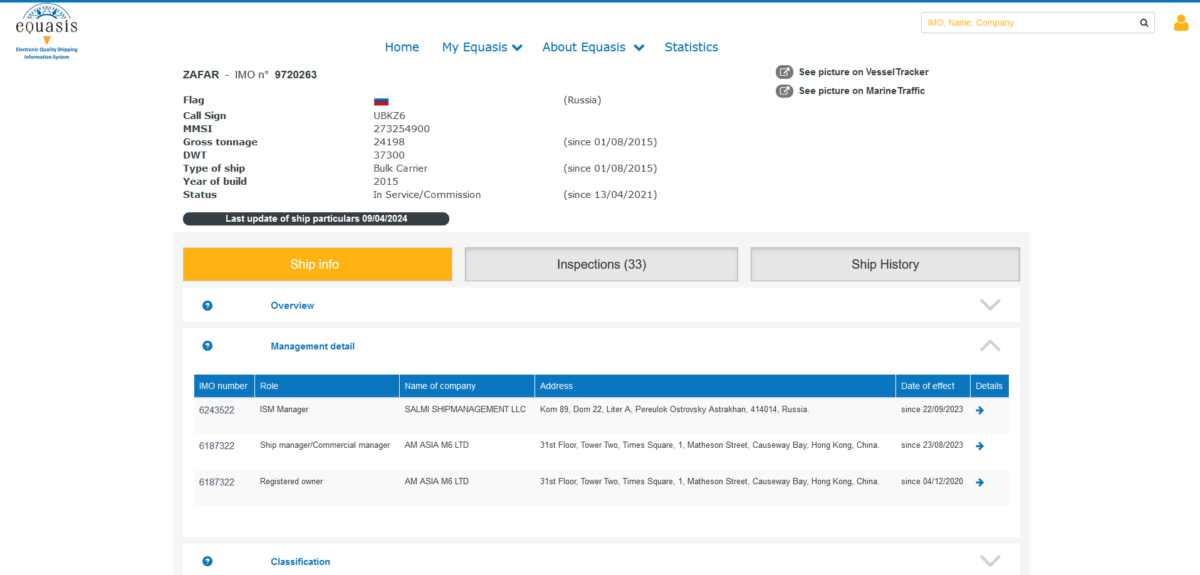

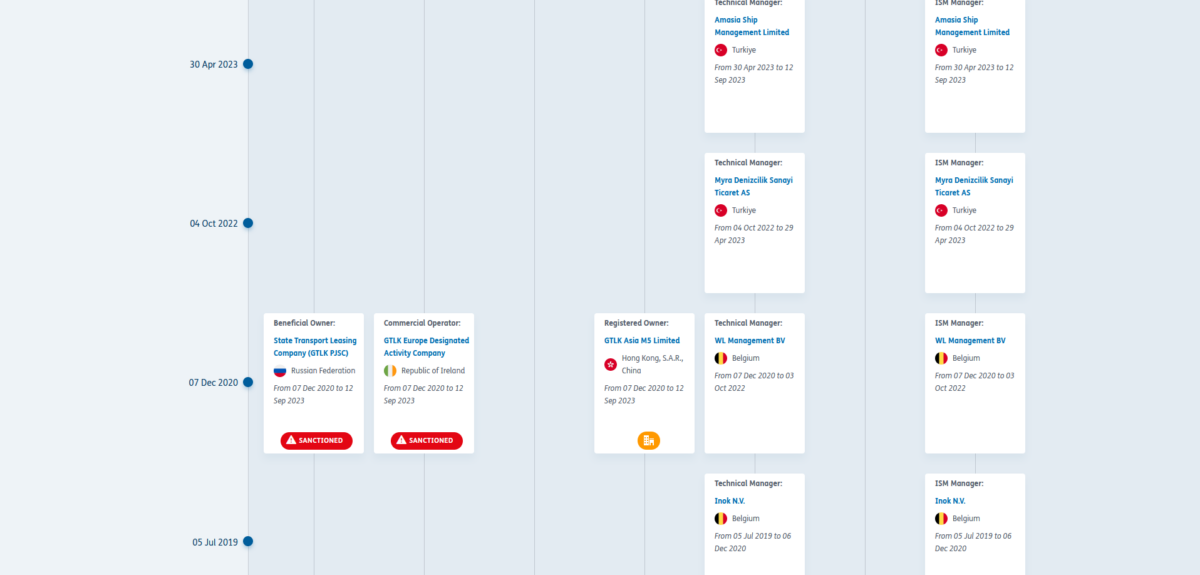

According to open source shipping data, Zafar and Zaid’s owners have at times been associated with the GTLK group, Russia’s State Transport Leasing Company.

The vessel ownership tracking database Equasis lists Zafar’s owner as AM Asia M6 Ltd. since August 2023.

The summary of a UK commercial court ruling from that January states that AM Asia M6 was part of the GTLK group, which is owned or controlled by Russia’s Ministry of Transport.

AM Asia M6 is mentioned in a list of companies which have changed their names published by the Hong Kong Companies Registry in November 2022. When inputting the corresponding company code from this list, the company appears under the name GTLK Asia M6.

GTLK was sanctioned by the UK government in April 2022. Its entry in the UK Treasury’s list of financial sanctions targets describes GTLK Asia as an ‘associated entity’.

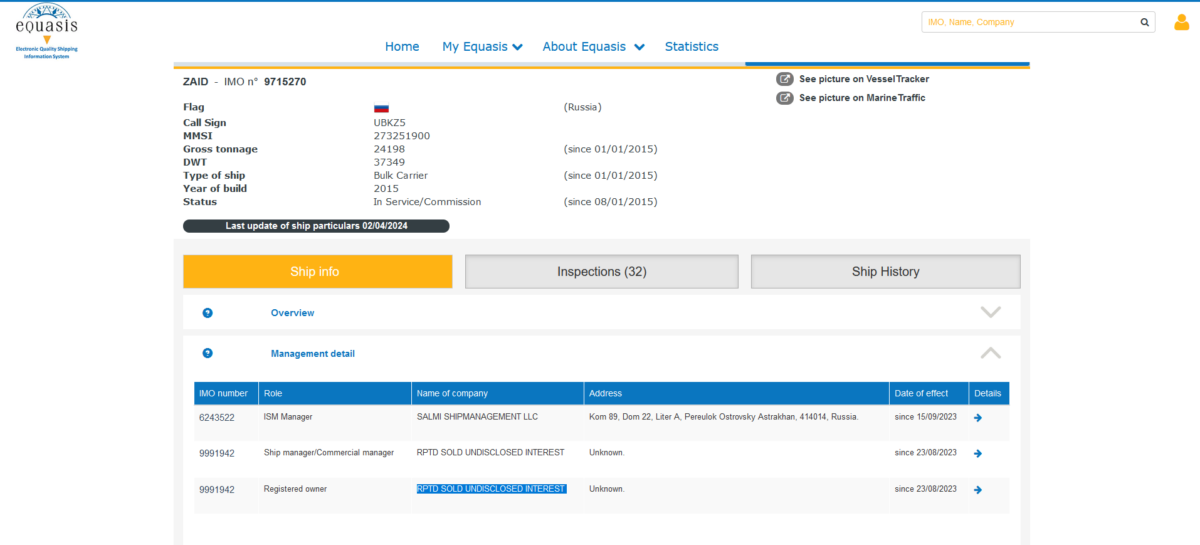

Equasis does not list Zaid’s current owner. The ‘registered owner’ field reads “RPTD SOLD UNDISCLOSED INTEREST”.

Maritime data website Lloyd’s List Intelligence, however, keeps track of vessels’ ownership history. The Zaid’s last known registered owner was GTLK Asia M5 Ltd, a Hong Kong-based company.

Over the same period of Zaid’s ownership by GTLK Asia M5 (i.e. from December 7, 2020 until September 12, 2023), its beneficial owner was listed as the Russian state-owned parent organisation GTLK PJSC.

OpenCorporates’ page for GTLK Asia M5 provides a company registry number. This number also appears in the aforementioned list published by the Hong Kong Companies Registry, where it refers to the company AM Asia M5.

The current beneficial owner of both vessels is not known.

Equasis also shows the Astrakhan-based Salmi Shipmanagement as the International Safety Management (ISM) manager for both ships — since September 22, 2023 for the Zafar and since May 15, 2023 for the Zaid.

The ISM manager plays an important role in the practical operation of a ship, explained Salvatore Mercogliano, a maritime historian at Campbell University in the US. “In contrast to its owner, a ship’s manager handles the crewing, husbanding, fuelling, and day-to-day operations of the vessel for the owner and potential charterer”, Mercogliano told Bellingcat.

New Year’s Voyages to the South

Iran may not have been the only destination for these two ships. The Ukrainian activist websites Myrotvorets and Kiborg News claim that both the Zaid and the Zafar sailed to Syria twice in January and February of this year.

As Bellingcat previously reported evidence of a link between the Avlita Grain Terminal and Syria, we sought to investigate the websites’ claims using open sources.

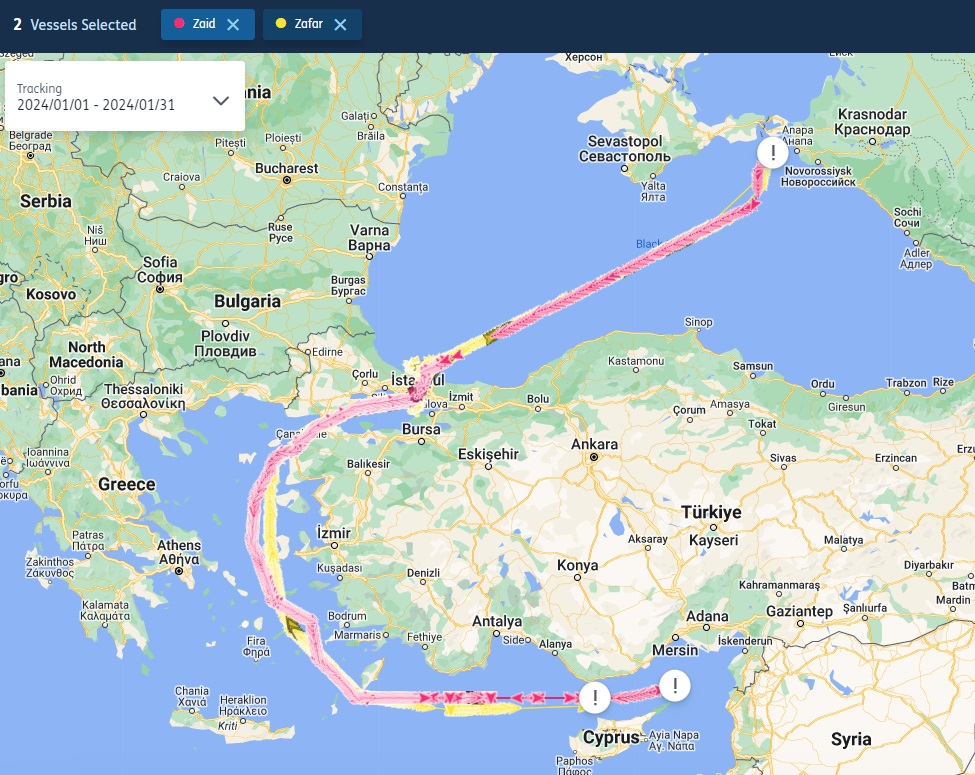

Lloyd’s List Intelligence AIS data shows that on December 28, 2023 the Zaid ‘went dark’ near the Kerch Strait. The vessel would only reappear on AIS tracking websites on January 5, 2024, in the same area.

The red arrows on the map below represent the known AIS coordinates of the Zaid in January 2024. Exclamation marks represent ‘AIS gaps’.

Once again, we looked for signs of the Zaid at the Avlita terminal during this period.

Planet Labs satellites captured the Zaid on January 1 docked at the Avlita terminal. The length and the breadth of the ship correspond with the Zaid’s as well, for reference see this tweet by MT Anderson.

The Zaid’s AIS signals resurfaced in the Black Sea on January 5. Once again the Zaid ‘went dark’, this time north of Cyprus on January 10.

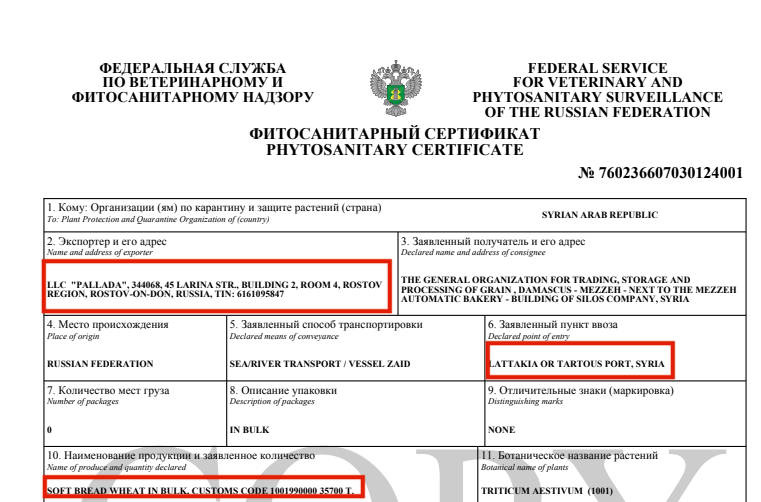

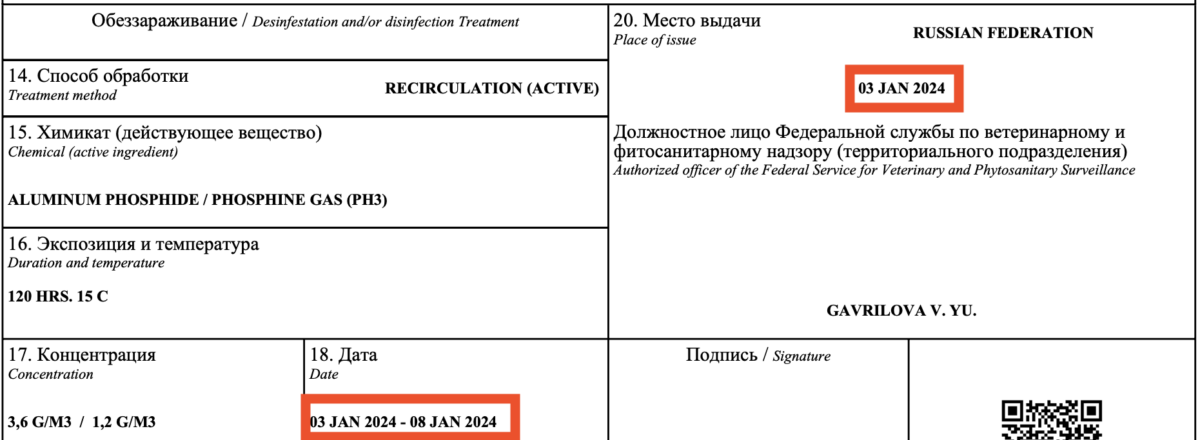

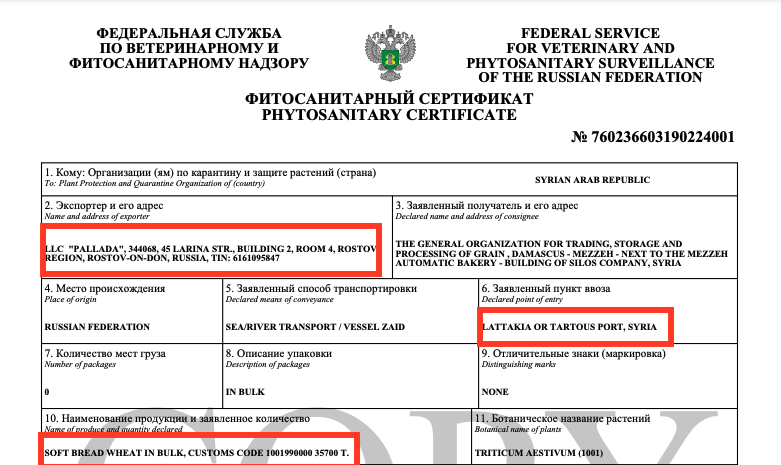

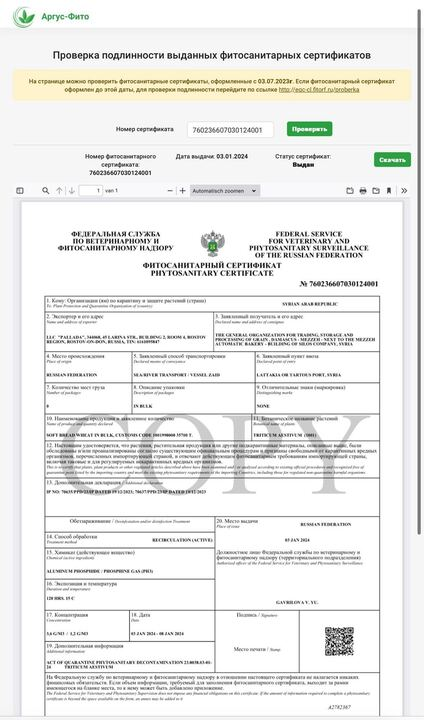

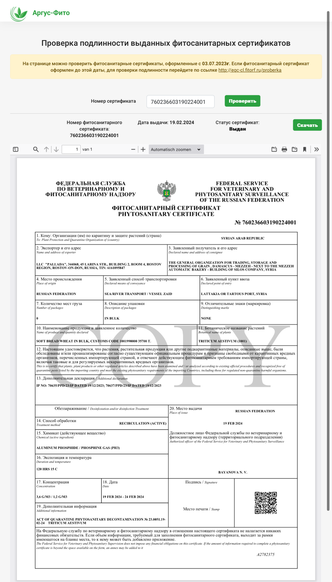

In their articles about the Zaid and Zafar, Myrotvorets and Kiborg News published four certificates from Russia’s Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Surveillance. This state watchdog, usually known as Rosselkhoznadzor, is responsible for checking agricultural products and livestock — including those sent by Russian companies for export.

This certificate published by Myrotvorets concern a shipment of ‘soft bread wheat in bulk’ aboard the Zaid destined for Syria, specifying the point of entry as either Latakia or Tartous.

This document’s date of issue is given as January 3, 2024 — two days after satellite imagery showed the Zaid at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol and two days before its AIS signal resurfaced in the Black Sea.

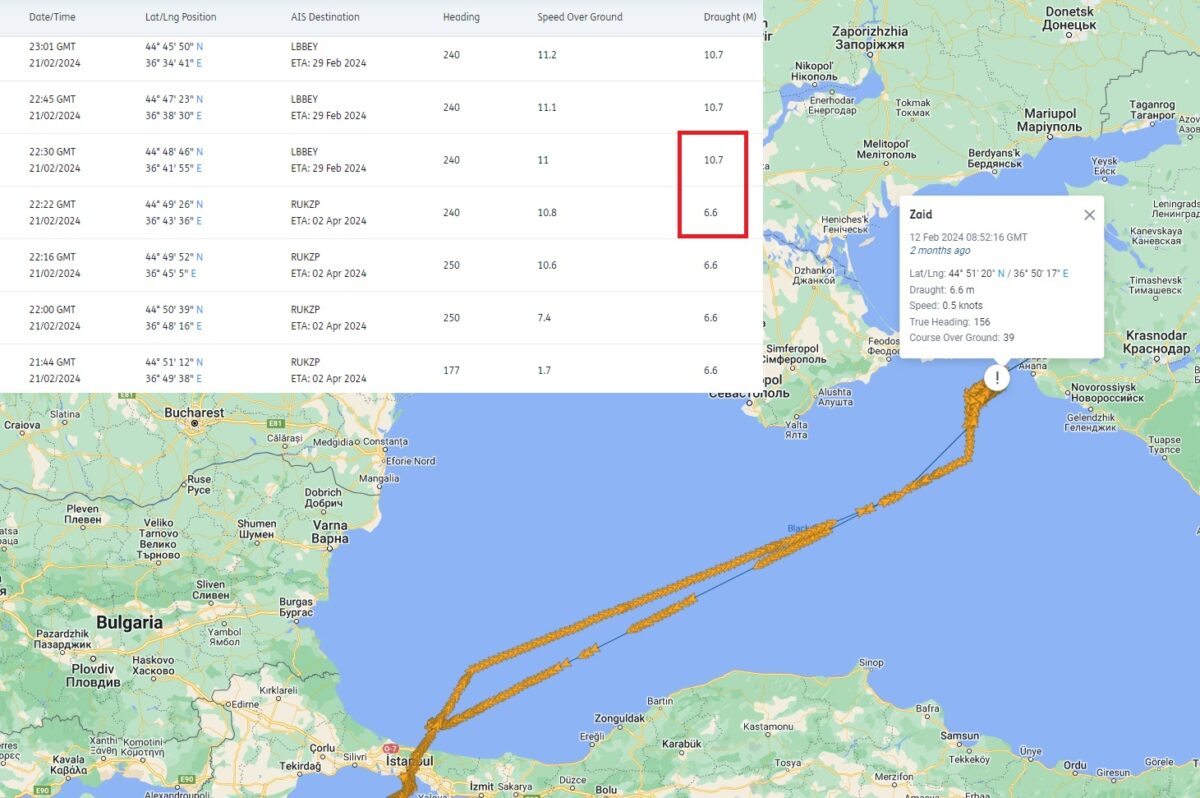

This process would repeat itself in February. Lloyd’s List Intelligence data shows that the Zaid went dark on February 12, again near the Kerch Strait.

Yet again, Planet Labs satellite imagery would capture the Zaid docked at the Avlita terminal during the period of its absence from AIS systems, on February 16.

The Zaid reemerged on February 21 near the place where it disappeared in the Black Sea. This ‘AIS GAP’ is represented by an explanation mark in the map below.

Lloyd’s List data also shows that the Zaid’s draft changed from 6.6 to 10.7 on February 21.

The Zaid went ‘dark’ again after March 1, when it was last seen north of Cyprus.

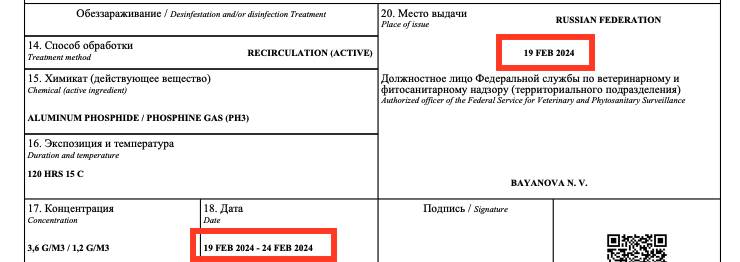

Once again, a document published by Myrotvorets concerning the Zaid’s activities in February gives the same details: it was carrying ‘soft bread wheat’ destined for Latakia or Tartous in Syria.

This document’s date of issue is given as February 19, 2024 — three days after satellite imagery showed the Zaid at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol and two days before its AIS signal resurfaced in the Black Sea.

When scanned, the QR code included in the bottom right-hand corner of these documents brought up a page on Argus-Fito, a Rosselkhoznadzor service for monitoring and issuing certificates issued by the institution. This page loaded the same PDF certificates published by Myrotvorets; all details were identical. The status of these two certificates is given as ‘issued’, which appears to indicate that they are authentic.

In both cases, satellite imagery confirms that the Zaid was berthed at Avlita a few days before these certificates were issued but not before it had again switched on its AIS systems. The documents do not refer to Avlita or Sevastopol, naming simply the ‘Russian Federation’ as the point of origin of the shipments.

However, open source information indicates that Pallada has at times played a role in supply chains involving the Avlita grain terminal in Sevastopol.

A December 18, 2023 court document from the Arbitration Court of Rostov Oblast names Pallada as a third party alongside Aval, the company which oversees operations at the Avlita terminal. The case concerned two Crimea-based companies and an allegation that one had delivered substandard grain. Both Aval and Pallada testified as to the quality of the grain, claiming that it had been returned to the provider.

The document does not mention Pallada’s customers nor where the grain was destined. However it does give the address of a Pallada warehouse in Sevastopol at 2 Primorsky Street — the same address as the Avlita terminal.

We cannot say for sure whether the Zaid reached Syria or if that was indeed its final destination, as satellite imagery for Tartous and Latakia ports for the dates after it ‘went dark’ in the Eastern Mediterranean is either unavailable or too cloudy.

Lloyd’s List also provided AIS data showing that the Zafar took a similar route to the Zaid twice during the same timeframe, ‘going dark’ in roughly the same locations. Myrotvorets also published two documents from Rosselkhoznadzor concerning the Zafar. However, Bellingcat was not able to corroborate the end points of the Zafar’s purported journey with satellite imagery — neither in Crimea nor in Syria.

Iranian Escapades

As mentioned earlier, bills of lading and similar documents are not available for the Zaid and Zafar’s trips to the Iranian port of Bandar-e Emam Khomeini. However, these voyages take place in a context of ambitious plans for deeper economic and transport ties between Russia and Iran.

The ships’ ISM is a small part of this picture. Salmi Shipmanagement was established in 2019 and its director is a man called Nikolay Yegorochkin. Russian business websites indicate that Yegorochkin was associated with other shipping companies, including a role as a director at Stal-Flot, a maritime shipping firm based in Astrakhan, Russia.

Astrakhan is a major port on the Caspian Sea which plays an important role in Russian trade with Iran — it is a much shorter option than transiting the Bosphorus and Suez to the Persian Gulf. Salmi has some prior involvement in Russian trade with Iran via this route.

Bellingcat found a document from the Russian Caspian Sea Ports Administration with a list of ships that requested ice-breaking services in January 2024. It shows that Salmi ships have also been active between Astrakhan and Bandar-e Anzali on Iran’s northern coast.

The ships belonging to Salmi were all empty when returning from Iran and loaded on their way there. While the document does not specify what the ships were carrying, they are listed as bulk carriers or dry cargo ships (Сухогруз in Russian), indicating a likelihood that the cargo on board was a raw or bulk commodity of some sort.

Russian firms also use Astrakhan’s port to export grain. Last October, Astrakhan’s governor announced that freight turnover for grain transshipment from the port had risen two and a half times compared to the previous year.

Why then would Russia have not sent the Zafar and Zaid’s 2023 shipments across the Caspian Sea? According to Nicole Grajewski, a Nuclear Security Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the longer route taken by the Zafar and Zaid is more logical. The port facilities on the Caspian Sea are “unable to handle larger types of ships and larger transfers of goods, whereas Bandar Khomeini is a large port which can handle container ships”, she explained. “It’s also probably more convenient because Russia has already taken these routes, stopping off at Turkey and Syria”, said Grajewski, who is the author of a forthcoming book on Russian-Iranian relations.

“Since the war in Ukraine, Iran and Russia have really ratcheted up their efforts at economic coordination”, said Nicole Grajewski, the Carnegie Endowment expert. “In general their trade ties have been weak, but there has been a consistent relationship when it comes to grain. Iran has been a major importer of Russian cereals”.

Bellingcat also discovered several visits to Iran made by Igor Rudetsky, whom Russian corporate registries describe as one of the founders of the Aval company whose Sevastopol-based branch conducts operations at the Avlita grain terminal. Rudetsky apparently holds or has held leading roles in a number of maritime companies including Sea Maker and PLC Caspy, which according to Russian state media is involved in port infrastructure in Astrakhan.

Rudetsky’s accounts on Instagram and Russian social network VK include several photos with Savchenko, a member of the Russian State Duma who is sanctioned by the US government (Rudetsky has also been quoted by Russian media in the capacity of Savchenko’s assistant). These photos also show that Rudetsky and Savchenko visited Iran together.

On October 26, 2023, Rudetsky shared a picture of the two of them on his Instagram page, with the caption ‘archive 2021’.

The men are standing in front of a replica of an ancient Persian statue inside a building. Two weeks before, he had shared another picture of a similar statue.

Matching features in the lobby allowed Bellingcat to geolocate the two images to the Espinas Hotel in central Tehran. These features are highlighted in the two screenshots below, taken from Google Maps’ Street View service.

This was evidently not the first visit. Rudetsky’s account on Russian social network VK is full of photos of business meetings with Iranian officials, Tehran street scenes, and videos and photos at meetings in the Mazandaran province, on the shores of the Caspian Sea.

On October 9, 2023, Rudetsky shared pictures taken at the port of Amirabad on Iran’s Caspian coast. He also posted photos in front of the office of Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Line Group (IRISL) in Tehran (35.799205, 51.474973).

Rudetsky also posted pictures of himself at business meetings.

The man standing on the right in the image to the left bears a striking similarity to Mohammed Reza Emami, an Iranian transport infrastructure official. In 2021 news website Purson.ir referred to Emami as the former Vice President of Development of Iran’s Ports and Maritime Organisation (PMO). Ten years ago the Bandar-e Anzhali and Chabahar ports also referred to him in that capacity. In 2018 Iran’s Ministry of Urban Development referred Emami as an official at the state air navigation company.

A number of clues in this series of photos posted by Rudetsky — namely a sugar pot and a view of a mosque — allowed Bellingcat to geolocate the meeting to the offices of Mostazafan Foundation in Tehran (35.740714, 51.420887).

The aforementioned Purson.ir reported that Emami was a member of the Board of Directors of the Mostazafan Foundation, using its full name: the Foundation of the Oppressed and Veterans of the Islamic Revolution. In 2020 the US Treasury sanctioned the foundation, describing it as an “ostensible charitable organization” serving the interests of Iran’s leaders.

“The Mostazafan Foundation operates as a financial conglomerate controlled by the IRGC”, said Afshon Ostovar, a professor at the US Naval Postgraduate School in California and an expert on Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). “[It] is involved in myriad schemes and business, invests in domestic and foreign ventures, and plays an obscure role in the importation of various products and services from abroad. It’s entirely unsurprising for directors with MF to meet with foreign counterparts, especially Russian. The IRGC does extensive business with Russia already, and one could imagine that there’s deep interest in both sides for expanding that relationship”, wrote Professor Ostovar in an email to Bellingcat.

We do not know what was discussed at these meetings nor if it had any connection to grain exports.

When asked about this meeting in a VK message from Bellingcat, Rudetsky told us that the meeting was part of a delegation led by the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs including about 40 people from “shareholders and managers of the Caspian, Black Sea and Baltic Ports”. He continued that delegation visited multiple organisations and was shown ports and management facilities by the Iranian side. The meeting “was neither of an intergovernmental nor of a state nature”, Rudetsky said.

A Growing Ghost Fleet

Cargo ships continue to appear at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol, usually after the deceptive practice of ‘going dark’ somewhere nearby in the Black Sea.

“What can this tell us? Only that the Russians have started to steal grain in large quantities from newly-occupied territories”, said Ukraine’s Prosecutor for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea Ihor Ponochovnyi when asked about the appearance of more ships at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol.

“Before the full-scale invasion the harvests in Crimea were not large… But after the full-scale invasion and the occupation of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions, the amount of grain supposedly produced in Crimea grew to an unrealistic amount. It’s understood that this is not Crimean grain. It physically can’t be in such volumes”, said Ponochovnyi in an interview with Bellingcat at his office in Kyiv. Ponochovnyi also claimed that Sevastopol’s port and the Avlita Terminal were on the verge of closure before February 2022.

When approached by Bellingcat for comment in a message on VK, Igor Rudetsky said that Aval has no relationship to the grain trade nor to any financial transactions concerning the transfer of grain overseas. He asked us to direct our questions about the shipments detailed in this article to the companies or ship owners responsible for purchasing grain.

“Aval only loads grain, provides stevedoring services and nothing more and there have been court cases where we have proven that we are not responsible for the quality of grain, which grain was brought to us or which grain we offloaded”, continued Rudetsky.

When asked whether he knew the origin of the grain loaded at the Avlita terminal, Rudetsky responded:

“No. Any trader who is interested in this or that quality of grain mixes different batches. Therefore a laboratory can’t determine its origin. It is profitable to transport grain by road up to distances of 1,200-1,400 kilometres. Draw a circle and you’ll understand that includes Astrakhan, Samara, Lipetsk. Along the Crimean bridge by railway to Altai and Orenburg. All these are grain producing regions with a surplus of about 30 million tonnes of grain for export. It’s hard to comment”.

Bellingcat also reached out to Salmi Shipmanagement, the director of Pallada Ltd., GTLK, the Mostazafan Foundation, the Iranian Ports Authority and Aval’s Moscow office but did not receive replies by the time of publication.

Youri van der Weide, Yöruk Işık and Maxim Edwards contributed to this report alongside Bridget Diakun of Lloyd’s List Intelligence. With thanks to Ross Higgins, Michael Sheldon and Annique Mossou.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.