More Europol’s “Stop Child Abuse” Photographs Geolocated

In November 2018, Bellingcat wrote about two photographs related to child abuse crimes – photographs which were geolocated to Shenzhen in China.

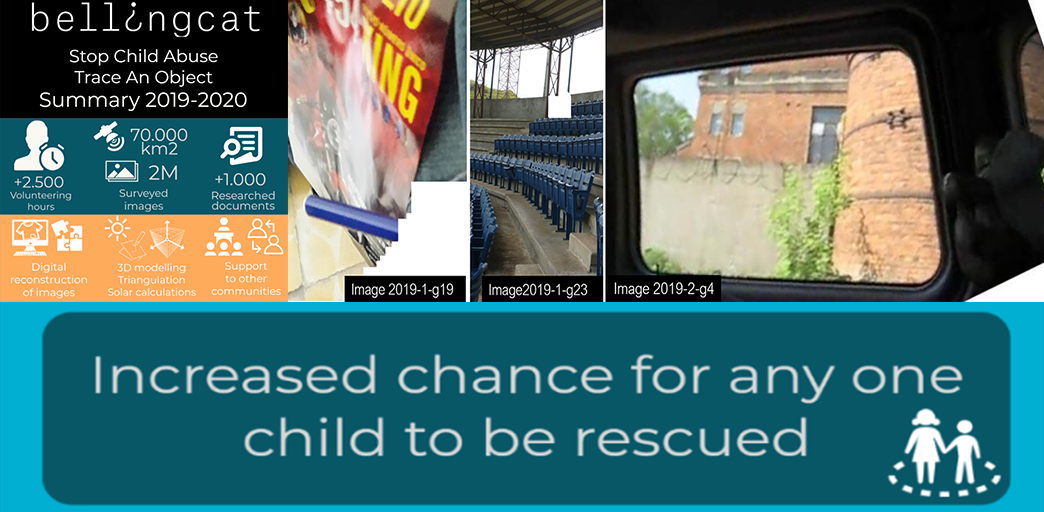

This investigation was crowdsourced by Europol as part of their Stop Child Abuse campaign that has been running since 2017. Images are shared on their website with the goal to identify the objects in them, their country of origin, and/or the location where they were taken. Europol also shares these images on their Twitter and Facebook accounts. Sites like Reddit and Websleuths will also share these images with the purpose of discovering their origin.

Both the campaign and the crowdsourcing efforts around it have not gone unnoticed by the media. The Guardian, for example, has written about Bellingcat’s involvement in this campaign. BBC News broadcast an interview with Finnish architect Olli Enne, who geolocated the two photographs from a city in East Asia, originally shared by Europol in October 2018.

On 1 February 2019, Europol shared new photos. Two of these photos were shared in a separate tweet. Just 23 minutes later, a Dutch citizen named Maarten Kaskens posted a reply with a photograph of the same place and mentioned the exact location, a cluster of summer homes between Moscow and Dmitrov, in a later tweet.

Soon, these photographs were removed from Europol’s website, likely because the right location was found, but also because the photographs directly led to the person who uploaded them. An account with geotagged photographs uploaded by this individual, taken in the same area, was deleted soon after Europol’s publication. The Bellingcat team investigated the photographs and the individual who uploaded them. We submitted details about the individual in question to Europol, but because of the ongoing criminal investigation into this suspect, we cannot reveal these details and can only discuss the photographs themselves.

Europol shared another photograph from their 1 February 2019 publication in a separate tweet on 22 February 2019, asking if anyone was able to recognize the city visible in the background. Shortly thereafter, an Italian citizen named Lorenzo Romani wrote that he recognized the city as St. Petersburg in Russia and uploaded a skyline photograph with a bridge that roughly matches the skyline visible in Europol’s photograph. Bellingcat found the exact location of the photograph, taken from a beach area near St. Petersburg.

Europol’s photographs from 1 February 2019 were also shared by Bellingcat. On the same day, several people responded to a photograph taken presumably in an East Asian city and recognized the writing on the building as Chinese and mentioned South China as a possible location because of palm trees visible in the photograph. Only the text on two billboards was clear enough for native Chinese speakers to read because of the photograph’s resolution. These billboards mentioned used car information and a brand of motorcycles from China. Further reactions to the tweet mentioned the island Hainan, Zhuhai, Shenzhen, Zhongshan and Jiangmen as possible locations. After searching in several cities in Southern China for streets with the same road lay out, street lanterns and palm trees, Bellingcat managed to find the exact location where the photograph was taken – in Jiangmen, China.

What follows below is a recap of how these aforementioned photographs were geolocated.

Location One: “Sunny Glade”, Yazikovo, Dmitrovsky district, Russia

The photograph presumably taken between Moscow and Dmitrov shows small houses and a pond in a rural area. Photographs uploaded to a website in 2003, show several similar houses and a pond – it obviously is the same area. One of these photographs, as tweeted by Maarten Kaskens, shows rocks with exactly the same paint marks as visible in one of Europol’s photos. During our research it became clear the photographs very likely were uploaded by the suspect in Europol’s case.

After comparing the photographs in the album to Europol’s website and first tweet from 1 February, it became clear that another photograph shared by Europol is from the same area. The small houses visible in the photographs are Russian summer houses (commonly referred to as “dachas”). Bellingcat discovered that the person who uploaded the 2003 photo album was registered to an address in Moscow in 2012, but also noticed an address of this person in Dmitrov mentioned in a discussion forum.

Left: Houses and a pond in a rural area, from Europol’s website and separate 1 February tweet.

Right: Another photograph from Europol’s website and a first 1 February tweet.

Left: Photograph from the 2003 photo album, showing stones with the same paint marks as one of Europol’s photographs.

Right: Another photograph from the 2003 photo album, showing the same houses as another Europol photograph.

Bellingcat also found a 2014 video, showing the same houses near the pond, as visible in the second photograph of Europol’s separate tweet from 1 February. Two individuals, who do not have anything to do with Europol’s case, and visible in this video have been cut out from the following screenshot.

Screenshot of the 2014 video (we left out the two people pictured), matching the second photograph of Europol’s separate tweet.

To confirm the exact location of these summer houses, we searched for additional evidence that supports the location of the deleted geotagged photographs. That evidence was found in a YouTube video, filmed from a car that drove from Moscow in the direction of Dmitrov, showing the route to the summer house area.

At one point in the video, when the car leaves the main road, a store named “minimarket Olgovo” is visible – its location is visible on Yandex street view. Apparently, a part of the video was cut out from that moment on, as a few seconds later a small old church is visible. This church was be geolocated to a village named Yazykovo, a short distance from Olgovo.

Following the road further south, the same road as is visible in the video eventually brings us to a cluster of summer houses named Solnechnaya Polyana (literally: “Sunny Glade”), owned by an organisation named SNT Solnechnaya Polyana, which runs many similar summer house communities mainly near Moscow.

Two screenshots from a video that shows the route from Moscow to the summer house community from Europol’s photographs.

Left: The church and houses in Yazykovo, near Olgovo in Dmitrovsky district.

Right: The entrance of the Solnechnaya Polyana summer house community near Yazykovo.

Eventually, the video also shows the exact location of the summer house of the suspect. This house matches with the 2003 photographs of the summer house. Bellingcat found the exact location of the summer house on satellite imagery and sent these details to Europol, but has chosen to refrain from publishing the exact location, due to the sensitivity of this criminal investigation.

Location Two: Olgino, Primorsky District, St. Petersburg Region, Russia

We first added more contrast to the photograph, which presumably was taken in St. Petersburg, so the skyline would be more visible. This enhanced version shows four pylons on the left side of the photograph, by which Lorenzo Romani recognized the skyline of St. Petersburg. Although we found many photographs with matching skylines, we noticed something was not completely right.

The most similar view we first found on Yandex streetview shows a different bridge on the left side of buildings similar to the buildings in Europol’s photograph, but that bridge has only two pylons, while in Europol’s photograph there are or there seem to be four pylons visible. The bridge with four pylons, as visible in Lorenzo’s tweet, is to the right side of these buildings. Also, the distance from the four pylons to the matching buildings in Europol’s photograph is bigger than in Yandex street view. Some of the buildings on Yandex street view are not visible on Europol’s photograph.

Then, we realized two things: Europol’s photograph was likely taken from a different direction; also, the photograph was a few years old and the skyline has changed during these years. Searching through older photographs and satellite imagery to check if the bridge might have been renovated, we found out that the bridge was built from 2014 to 2016 and the two pylons were constructed in 2015.

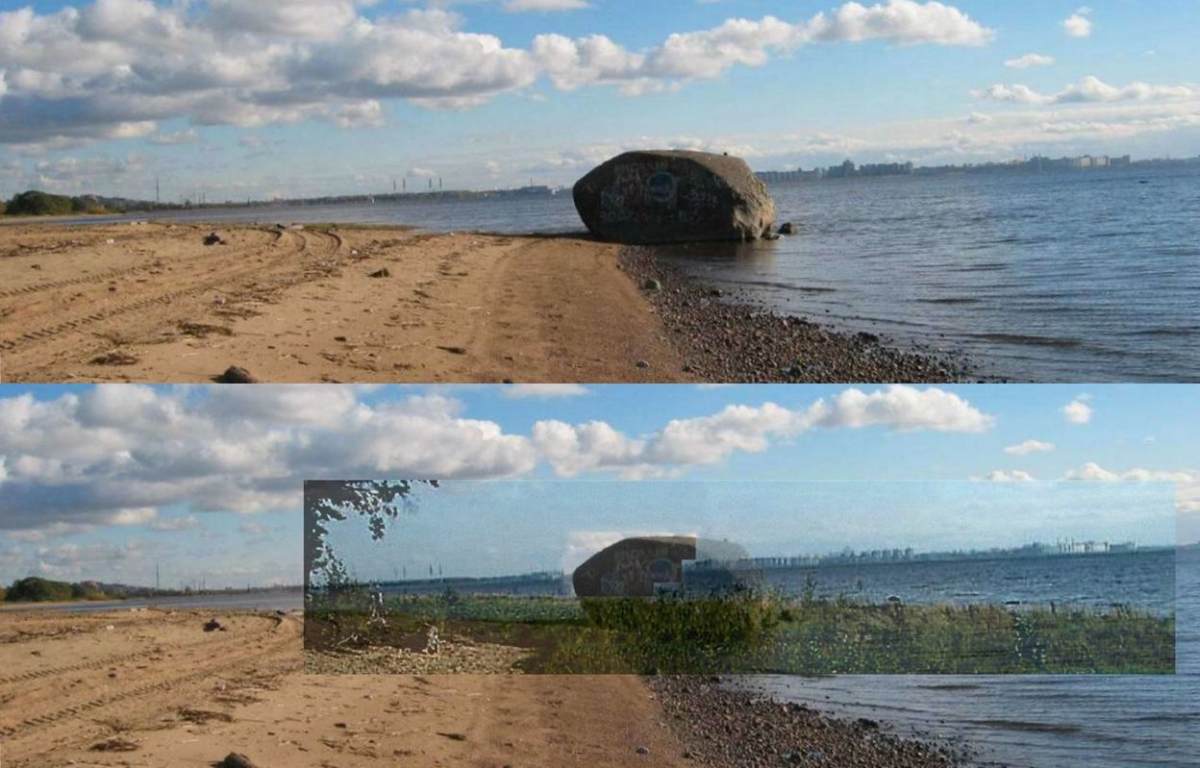

Enhanced version with more contrast of Europol’s photograph.

Comparing the skyline in Europol’s photograph to Yandex streetview shows similarities, but also a few differences. The four pylons in Europol’s photograph are further away from the buildings than the bridge and some buildings seem to be missing in Europol’s photograph.

Older photographs of the area show the same skyline without the bridge and several other photographs. Also, Yandex street view shows a soccer stadium to the left side of the bridge with several light poles.

However, satellite imagery shows the stadium has eight light poles instead of four and the light poles stand skew instead of straight as in Europol’s photograph. Older satellite imagery makes clear that construction of the current stadium, named Gazprom Arena or Krestovsky Stadium, started in 2009 at the location of the former Kirov Stadium, which was demolished in September 2006. The Kirov Stadium had four straight light poles, matching the four poles visible in Europol’s photograph.

Top: Skyline from 2010 without bridge and construction work to the left.

Middle: Skyline from 2007 that closely matches Europol’s photograph skyline.

Bottom: Skyline from 2018 with bridge and soccer stadium.

Photographs taken from the beach area around the Thunder Stone (“Гром Камень” in Russian), a large megalith used in the 18th century as pedestal for the Bronze Horseman in St.Petersburg, seem to have the best matching skyline. In a photo album connected to a 2004 article about the Thunder Stone, a photograph that was uploaded in October 2004 shows almost the same skyline as visible in Europol’s photograph, including the four light poles of the old soccer stadium. An overlay of Europol’s photograph over the 2004 photograph shows the striking similarity of the skyline.

Top: 2004 photograph of the “Thunder Stone” beach area showing a very similar skyline as Europol’s photograph.

Bottom: Overlay of Europol’s photograph over the 2004 Thunder Stone beach area photograph.

In Europol’s photograph it seems a few taller buildings are visible that are not visible in the 2004 Thunder Stone beach area photograph. This can be explained because construction of a residential complex named Morskoy Kaskad (literally: “Sea Cascade” in Russian) started in 2003 and was finished in 2005. Therefore, Europol’s photograph very likely was taken between spring and autumn 2005, or in the spring or summer of 2006.

Location Three: Jiangmen, Xinhui district, Guangdong province, China

One of the locations published by Europol on 1 February, which was not tweeted about separately, is accompanied by the question, “Do you recognize this building in Asia?”

In response to this tweet, as well as to Bellingcat’s tweet, several people responded by saying that they recognize the text displayed on several billboards on the building as Chinese and that the location was very likely to be in South China, because of the palm trees visible in the photograph. Only the text on two billboards is clear enough for Chinese speakers to read because of the photograph’s low resolution. The billboards mention used cars and a brand of motorcycles from China. As previously mentioned, further reactions to the tweets specifically mention the island Hainan, Zhuhai, Shenzhen, Zhongshan and Jiangmen as possible locations in South China.

Building in South China with two readable billboards, displaying the name of a brand of motorcycles from China (bottom left) and “used car information” (bottom right). The image obviously has been edited/censored by Europol, because very likely a child was visible in the original image.

Twitter user Ben Lokshin, among others, deciphered the motorcycle brand billboard as “中裕摩托“, written in simplified Chinese characters and translated as Zhongyu Motorcycles. Another Twitter user named Konrad Iturbe pointed out this brand is sold all over China, but also mentioned that only Jiangmen would have this kind of architecture, road layout, and palm trees.

A Twitter user named James noticed a photograph of a different building with the same first four Chinese characters displayed on a billboard – a logo for a motorcycle repair service department. That repair service deparment, however, is on Taoyuan west road 35 in Mabazhen in the Qujiang district, Shaoguan, Guangdong province, more than 100 kilometers north of the other aforementioned cities in Southern China. Both Google as Baidu, showing yet another building with the same four Chinese characters on a billboard, give Hiuanshi 3rd road, Penjiang district in Jiangmen city, Guangdong province in Southern China as the first search result first “中裕摩托” (Zhongyu motorcycles).

Nathan Ruser from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, among others, recognized the text on the second billboard as simplified Chinese characters “二手车信息”, translated as “used car information.”

Zhongyu motorcycle repair service department in Mabazhen, Qujiang district, Shaoguan, Guangdong province, China (left),

Zhongyu motorcycle accessories in Penjiang district, Jiangmen, China (right).

Further research into the brand name “Zhongyu motorcycles” made clear the company that produced these motorcycles went bankrupt in 2006 and the owner fled China, despite being ranked first in 2005 as motorcycle production in China and that everyone in Jiangmen knew the factory closed down.

The location of the factory, which is only correctly displayed on the Chinese version of Google maps, was on Jinlu Road in the Jianghai District of Jiangmen City. The Zhongyu motorcycle group was established in 1994 and produced 600,000 motorcycles a year on the 420-acre industrial park in Jiangmen. A 2002 archived version of Zhongyu motorcycles’ website mentions the engines were produced in the Wuhe indsutrial zone in Daze town in the Xinhui district of Jiangmen.

Because Zhongyu went bankrupt in 2006, we suspected the Europol photograph to be at least ten years old, as after 2006 very likely no new advertisements of this motorcycle brand would appear anymore on billboards. Since these motorcycles were produced in Jiangmen, we knew there was a chance that Europol’s photograph was taken in Jiangmen, despite that these motorcycles likely were sold everywhere in China – or at least everywhere in South China. Our research started in various cities in South China and we especially focused to the layout of the road visible in the photograph: a two-way road with three lanes each, separated by a centre median strip with palm trees and lamp posts with four lights.

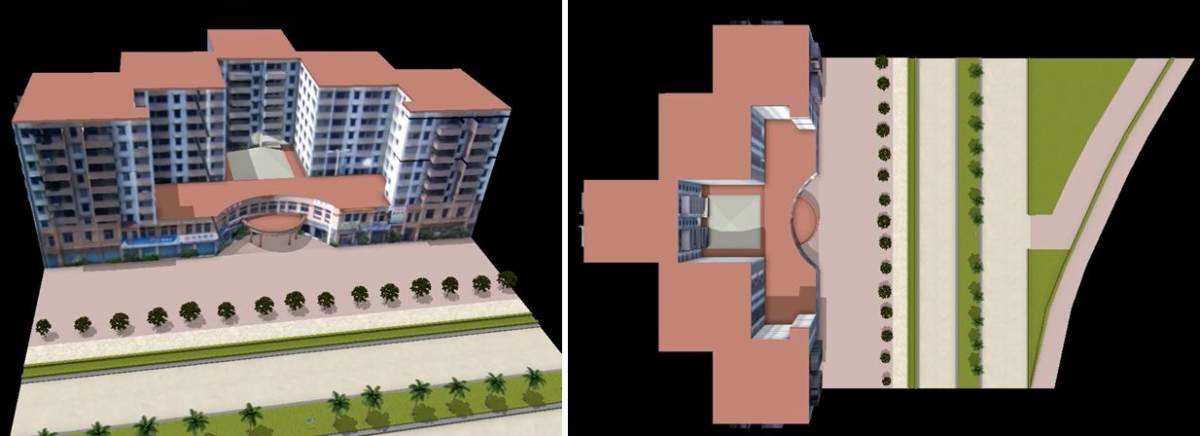

After an intensive research, we finally found such a road and a similar building in the Xinhui district of Jiangmen, named Sanhe Avenue. However, the building from Europol’s photograph was not found along this road. As satellite imagery in Jiangmen doesn’t go back further in history than 2008 and Europol’s photograph was likely taken in or before 2006, we realized there was a chance the building was demolished before 2008. As we expected to find the building along this north-south road, on the west side of the road based on the direction of the sunlight, Timmi Allen of our Bellingcat team created a 3D model of the building to understand how the building would look like on satellite imagery.

3D reconstruction model of Europol’s Asian city photograph, showing recognizable features of the building.

Via this reconstruction model we eventually found the building on Ganzhou Avenue East 88 in the Xinhui district of Jiangmen, China. According to geotags on Baidu and Google, the building houses, among other businesses, a used car information center and a business hotel, showing the same entrance on the hotel website as Europol’s photograph.

Baidu’s street view from 2015 even shows the exact same lam post and blue one-way traffic sign on the centre median strip with palm trees. Examination of satellite imagery clearly shows Europol’s photograph was taken before 2014, as a building to the right of Europol’s building has been demolished before 2014 and a new building to the left was built before 2014. Also the height of the trees visible in Europol’s photograph fit the 2008 satellite imagery.

The building from Europol’s Asian city photograph on Google Earth satellite imagery of 2018 (top left) and satellite imagery from 2008 (top right). Baidu’s street view from 2015 of the same building and road visible in Europol’s photograph.

The photograph that Europol published was taken from behind a window of the building on the opposite side of the street. Europol’s photograph shows a black fence, big windows and two white pillars on the other side of the window. Also a white roof is visible on the bottom side of the photograph. The photograph clearly shows this part of the building has a round shape. A white cross and a car on the left side are visible outside in the area which seems a parking place. Baidu’s streetview shows a part of the building with a round shape and a roof above the entrance. On the second floor of this part of the building, a fence is visible behind the only window that is not covered by a curtain.

The street view to the third floor of the other side of this building shows a black fence with exactly the same shape as in Europol’s photograph. However, since a large part of the roof above the entrance is visible, it’s more likely the photograph has been taken from the second floor, from one of the rooms that, on street view, has its windows covered by curtains. Photographs taken in meeting rooms of the building, which in the meantime have been deleted, also show the exact same type of fence.

The building where Europol’s photograph was taken. A similar fence is visible on the second floor (left)

and the exact type of fence on the third floor (right). Large windows, white pillars and a white roof above the entrance are similar to Europol’s photograph.

Photographs taken from meeting rooms in the building where Europol’s photograph was taken

show the exact same type of black fence as in Europol’s photograph.

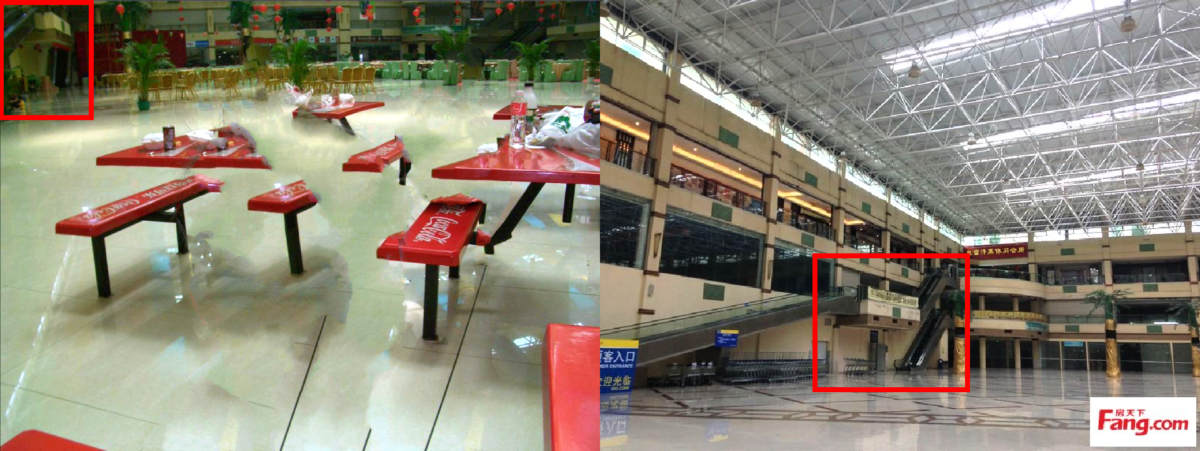

Further investigation into the building where Europol’s photograph was taken, led to the surprising conclusion that another photograph, published by Europol on 1 February 2019, was taken inside that same building. This photograph, showing a hall of what looks like a shopping center and several red tables and benches with “Coca Cola” written on them, is accompanied by the question “Do you know where this food court is located?”

An article about the Jianghui Times City (archived here), published in July 2013, shows a photograph of a central hall of this shopping mall, which shows many similarities to Europol’s food court photograph. Another article about the same shopping center published in 2014 (archived here), confirms the location.

Another photograph published by Europol on February 1, 2019 shows a hall inside what looks like a shopping mall, with several red tables and benches visible in the photograph with the Coca Cola logo displayed on them (left). Photograph of the hall of the Jianghui Times City shopping mall, the building from where Europol’s Asian city photograph had been taken from (right).

Comparison between another photograph of the main hall of the Jianghui Times City shopping mall

to Europol’s food court photograph of 1 February 2019.

Conclusion And Recommendations To Europol

This analysis demonstrates that Europol’s “Stop Child Abuse” online crowdsourcing campaign is quite succesful. It’s not only that objects in photographs get recognized often, so that they can be linked to an origin country making it possible for Europol to inform law enforcement of said country in order to further investigate the case. Sometimes, often after intensive research, locations of photographs eventually get geolocated precisely, possibly increasing the likelihood that such a case can be solved.

However, we have a few recommendations to Europol in their crowdsourcing campaign. The first recommendation is to be careful with sharing photographs that can be easily found with reverse image search, as this could immediately lead to a victim or even a potential suspect. The risk for vigilante justice can be high, particularly if a social media profile belonging to a potential suspect or person of interest is uncovered. When it came to Location One, it was relatively easy to find one of the photographs with reverse image search, which happened just less than half an hour after one of the photographs was tweeted by Europol.

The second recommendation is this: If several photographs from the same case are displayed on Europol’s website and Europol is aware of these photographs as being linked, it can help to make the connection between the photographs clear. Both in the case of Location One and Location Three it became clear Europol uploaded two different photographs that are part of the same case, without specifying it. It’s possible that this information could help solve the case possibly even quicker.

Our final recommendation: Before a photograph is shared, it would be good to be realistic about the chances for recognition. Sometimes the quality of the photographs of objects seems too low to be able to be recognized and sometimes the location seems as if it could really be anywhere and could not be geolocated without any background information. This is why we recommend sharing as much information about a certain location as possible, in case that information is available. Our next article in the series of Europol’s “Stop Child Abuse” will show an example of a photograph that like would never have been geolocated if no additional information was found about the image.

Research by Daniel Romein, Timmi Allen, Klement Anders, Noor Nahas and “Bo”, review/editing by Natalia Antonova.