Nefarious Negligence: Post-Conflict Oil Pollution in Eastern Syria

Since the so-called Islamic State lost most of its control over oil resources in northeast Syria, various groups have replaced them to take control over the oil infrastructure–or, at least, what is left of it. In the recent Bellingcat article, Hazardous Legacies, an overview was provided of the damaged oil industrial sites and clusters of artisanal oil refineries across the landscape of the Deir az Zor, Hasakah and Raqqa governorates.

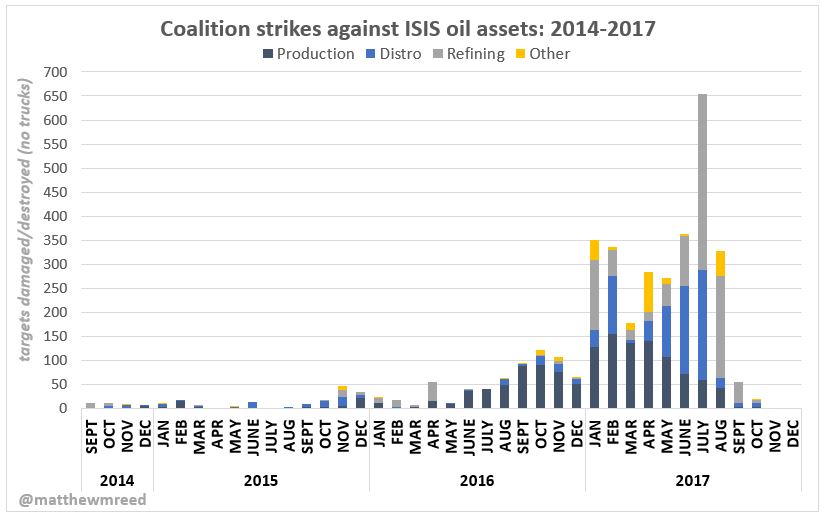

Years of bombing by the US-led Coalition and Russian Air Force, combined with fighting around and attacks on oil refineries, have resulted a severely damaged oil industry. A recent analysis of Coalition airstrikes demonstrates the magnitude of targeting oil infrastructure that caused widespread localised environmental pollution.

The practice of artisanal oil refining is already taking a toll on the health of many Syrian civilians, including children, who work in these toxic conditions to make a living. The real long-term environment and health impact is yet to be determined, though going by what open-source data tells us, this pollution legacy will require significant research, clean-up and remediation work. This article will use open-source imagery from Planet Labs and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel 2 to look at recent oil spills incidents in Deir az Zor. A series of serious incidents cause kilometres-long oil spills in the wake of the conflict, causing long rivers and lakes of crude oil. This happened both in areas retaken by the Russian-backed Syrian Arab Army, and in territories controlled by the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). This article will also, in line with United Nations Environmental Assembly Resolution EA/3/Res. 1 [PDF] on Conflict Pollution, outline routes for implementation of this resolution to deal with potential acute and chronic environmental health risks to workers and nearby communities.

Our main findings:

- The absence of expertise at several oil industry locations, combined with air strikes against oil infrastructure, resulted in the build-up of rudimentary crude oil storage in makeshift surface reservoirs since 2013.

- Oil spills have occurred at several of these reservoirs and nearby pipelines, resulting in localised environmental damage due to leaks or mismanagement.

- At three refineries retaken from IS, significant oil spills occurred in late 2017 and early 2018, resulting in kilometres-long oil spills that were visible on satellite imagery. The cause of these spills are unknown, but could be attributed to absence of relevant on-site expertise, safer alternatives, and an unfortunate combination with heavy rainfall causing spread of crude oil over larger areas.

Increase of rudimentary oil storage

As outlined in the previous article, due to an intense air campaign to target IS oil revenues, oil storage facilities have been seriously damaged. As an alternative to oil storage facilities, crude oil was still being pumped but instead stored in reservoirs, as seen in the below Google Earth image of a reservoir at the Isba oil field. These types of makeshift reservoir for crude oil storage can be found near most of the oil fields in Deir ez Zor and bring with them significant risks of localized pollution.

A good example of this practice is the reservoir we previously reported on where an oil spill occurred at an oil well near the Conoco Gas and Oil facility, currently controlled by the SDF. Various dams had to be build to stop the oil from flowing, while Google Earth satellite imagery also shows activity at the location, with tanker trucks loading crude oil.

At the time of writing this article, there is still an ongoing fire at this location, as shown on Sentinel 2 imagery dating March 31, 2018 (using Agriculture option Sentinel Hub to show heat signature)

Satellite imagery from the last 6 months revealed major oil spills at three locations which we will discuss below, and some additional concerns over the wider oil pollution caused by targeting of oil industry sites and the use of artisanal oil refineries.

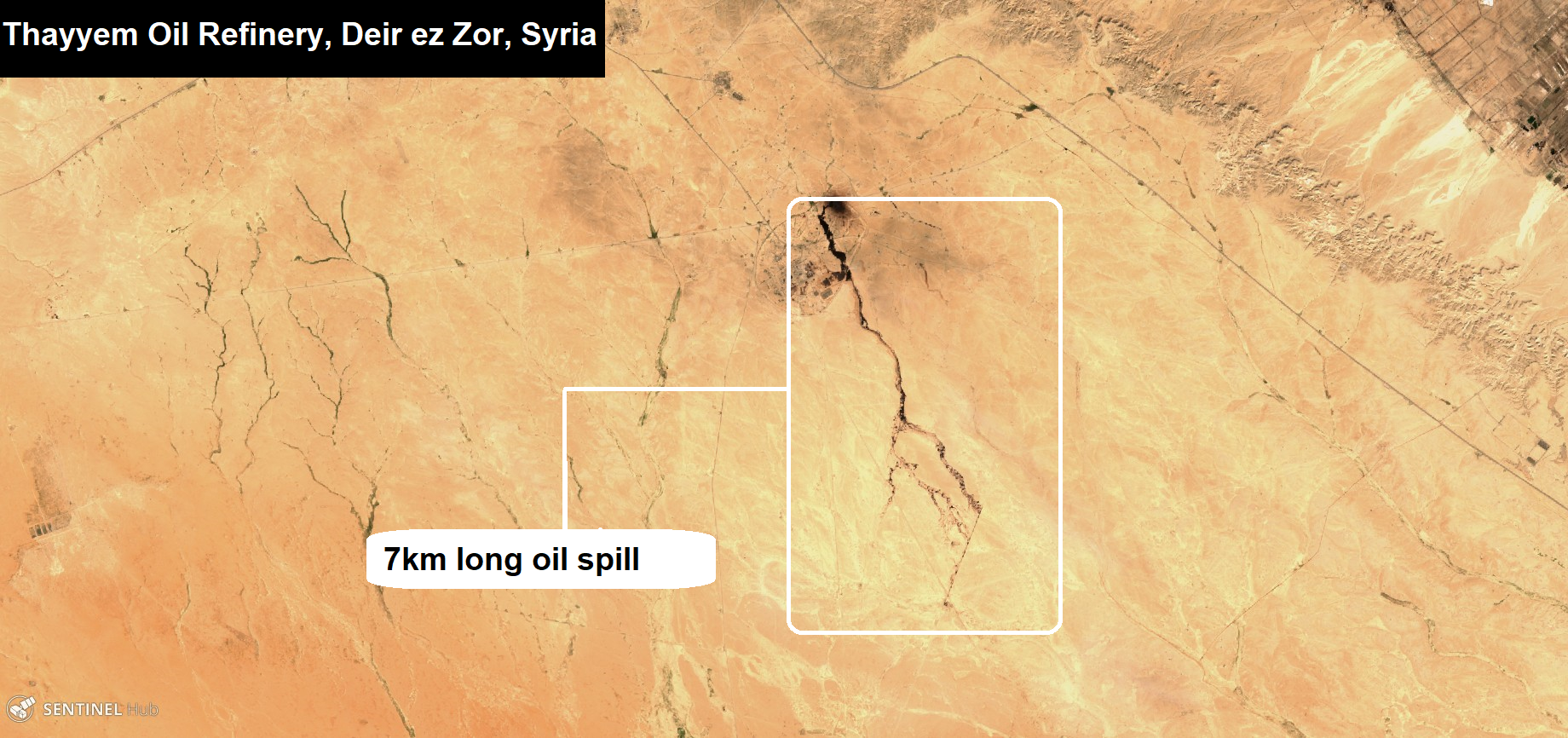

Thayyem oil refinery

This refinery south of Deir az Zor city was already bombed multiple times by the Russian Air Force in 2015, as shown by Twitter user @obretix’s geolocation of videos uploaded by the Russian Ministry of Defence.

RuAF Tu-22M airstrike near Deir Ezzor (Thayyem oil field) geolocated https://t.co/9EZaWYH12r https://t.co/tqWqR7lqaZ pic.twitter.com/ibkeMpUVRK

— Samir (@obretix) November 22, 2015

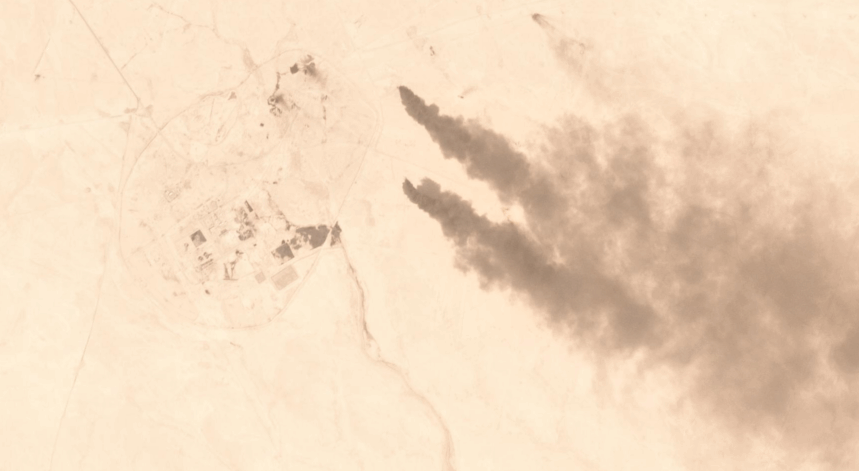

In September 2017, Russia-backed Syrian troops retook to the oil fields near the Thayyem refinery. In the course of the fighting, some oil wells were set on fire, as visible on satellite imagery from Planet Labs from September 10, 2017. The imagery can be corroborated with footage from the ground showing Syrian troops advancing towards the city, uploaded on September 16, 2017.

In the course of battle of the refinery, oil pipelines were damaged, creating a huge oil spill in the northern part of the site.

However, the situation got worse, as between February 19th and February 24, oil started to flow out from the refinery, causing a 7km long oil spill south-est of the refinery, visible on ESA Sentinel 2 imagery below. This was caused by mismanagement of local oil storage, and likely combined with heavy rainfall in that period, resulting in the dispersal of crude oil.

Abu Hardan oil field

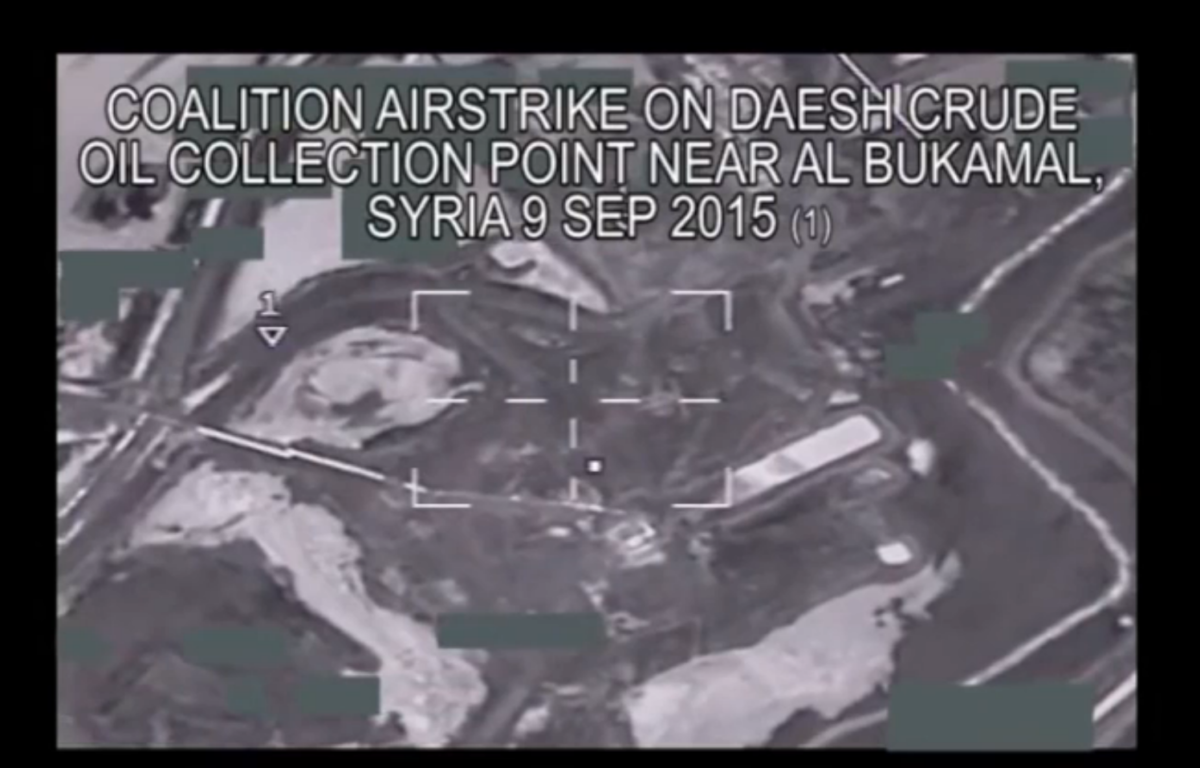

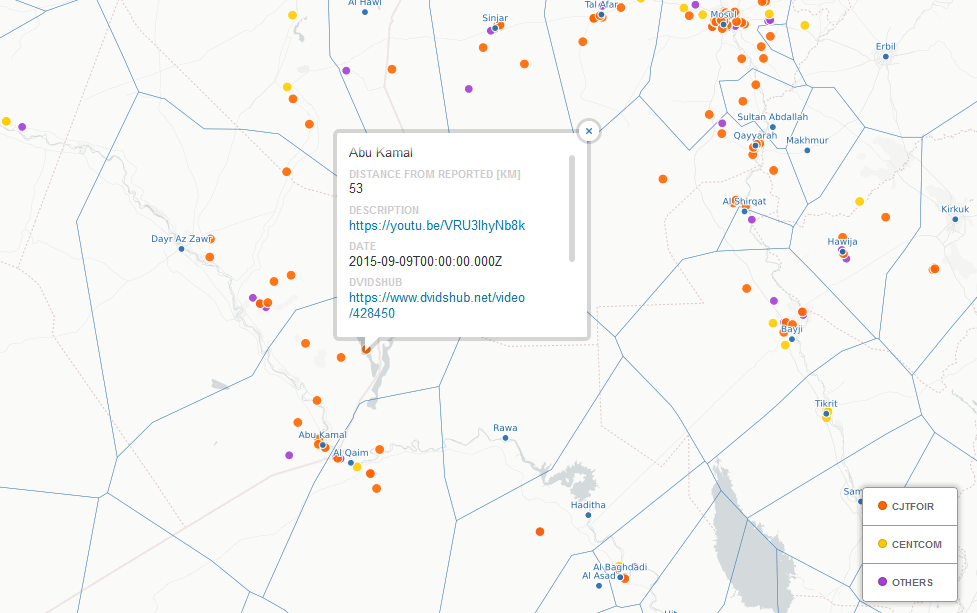

This oil field is located 45 kilometres northeast of Abu Kamal, on the border with Iraq. Several strikes took place at wellheads over the course of the last two years, leaving some small bomb impact footprints on wellheads at the location. This US DoD video shows one of the strikes at the wellhead on September 9, 2015, as geolocated by @Obretix.

Between March 5 and March 7, 2017, likely weather conditions and/or human error resulted in a wider spread of crude oil over larger area near one of the crude oil storage basins.

Source: Planet Labs

Jafra Central Processing Facility

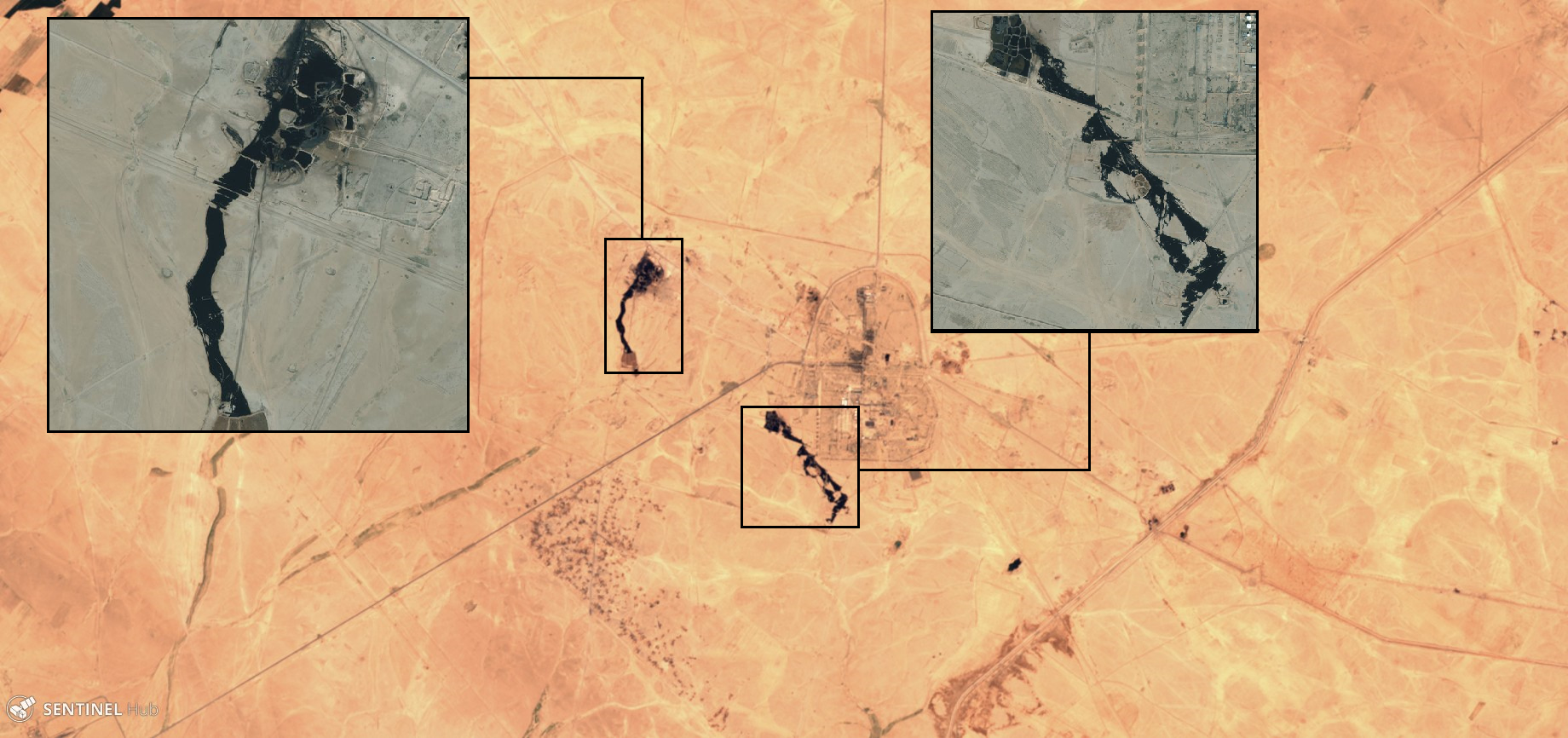

The Jafra Oil and Gas separation plant lies on the northern side of the Euphrates river, and the oil field itself was one of the first locations to be targeted by the US-led Coalition in Syria. In 2015, the Russian Air Force directly targeted the refinery, while nearby wells and collection points were repeatedly hit by Coalition strikes in the following years. The oil fields and Jafra CPF were retaken in late October 2017, and the fighting resulted in outbreak of oil well fires at nearby wells and crude oil reservoirs.

Latest update on oil pollution around Jafra oil facility in #SDF controlled areas #DeirEzzor based on #LANDSAT8 imagery Oct 21 pic.twitter.com/MPBv1CM7D7

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) October 23, 2017

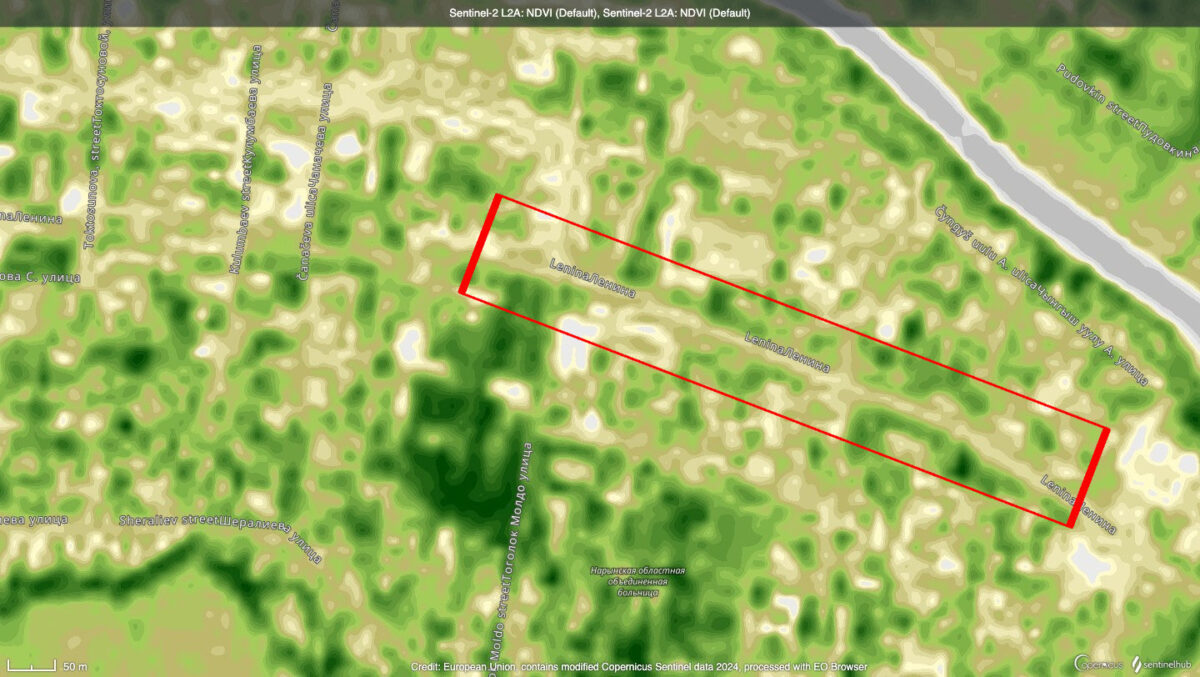

Over the past two years, a large number of the reservoirs storing crude oil from nearby wells have been built near the CPF. As these reservoirs were fairly rudimentary in nature, they were at risk of being seriously damaged. After the major hostilities ended near the Jafra CSP in late 2017, satellite imagery shows that for unknown reasons, oil started leaking from two major cluster of reservoirs west and south of the refinery, resulting in two oil leaks of (respectively) 800 meters and 1500 meters long.

Other oil spills

On February 19, 2018, a video appeared on Facebook, which was also posted by the pro-Assad online group Syria General, stating that an oil pipeline was hit by Syrian army troops while digging trenches near Abu Kamal. Unfortunately, we have not been able to geolocate this site. Available satellite imagery near Abu Kamal doesn’t showing any sign of an oil spill of that size.

So while #SAA were trying to dig trenches near Abu Kamal, oil suddenly started gushing out. pic.twitter.com/VIg5bNLHOy

— /sg/ SOURIA GENERAL (@SyriaGeneral) February 19, 2018

Various smaller size oil spills at well-heads and storage facilities can be found near almost all of Deir az Zor’s oil fields, most of them linked to directly targeted by air strikes, or mismanagement with oil loading after the ending of major hostilities.

Tankers trucks loading up crude oil at oil wells close to Tanak oil facilty. Oil well was targeted by @CJTFOIR strike in 2017, causing huge oil spill. Before and after image. pic.twitter.com/A6nebtpIjn

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) April 4, 2018

Various clusters of makeshift refinieries continue to be operated in the areas, compounding concerns over further toxic working conditions for children and the wider polluting practice of artisanal refining, that will likely to remain a major source of income for local communities.

Polluting practices of artisanal #oil refining continue under SDF control in Deir Az Zor. Recent Sentinel2 imagery from April 4, 2018 shows fire at makeshift cluster south of Jafra CSP (Agriculture band) pic.twitter.com/R7sxDkxvgQ

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) April 8, 2018

Pollution Mitigation? Avenues for tackling environmental health risks

In the aftermath of the defeat of IS in Deir az Zor, responsibility for dealing with conflict pollution was laid with the new authorities in both Syrian government and the SDF in areas they control. With significant damage to Syria’s oil industry and resulting unsafe storage and refining processes started by local actors, there is an urgent need for identification, clean-up and remediation of affected sites. Oil spills cause localized pollution and affect soil and groundwater, and these risks can be compounded with the practice of makeshift reservoirs, built to store crude oil. At the same time, hazardous working conditions associated with crude oil transporting or artisanal refining can cause serious health risks to workers at these locations, many of whom are children.

Addressing conflict-related environmental pollution was one of the major outcomes of the 3rd UN Environmental Assembly meeting that took place in Nairobi in December 2017. The resolution, titled “Pollution mitigation and control in areas affected by armed conflict of terrorism”, was the outcome of a long negotiation process, in which some States, who were also active in targeting Syria’s oil infrastructure, objected to specific language on target selection on pollution prevention.

Despite this, the resolution, adopted by consensus, expresses its concern regarding environmental damage and the depletion of natural resources in the territories affected by armed conflict or terrorism, while also “[n]oting the long-term social and economic consequences of the degradation of the environment and natural resources resulting from pollution caused by armed conflict or terrorism, which include, inter alia the loss of biodiversity, the loss of crops or livestock, and lack of access to clean water and agricultural land.” The resolution also notes how absence of environmental governance “can lead to inadequate waste management and dumping, while the loss of economic opportunity can compel affected communities to pursue unsustainable and polluting coping strategies.” Clearly, Syrian communities have been witnessing these polluting coping strategies, with likely thousands of children working in toxic conditions refining crude oil to make an income, while local experts warn of the serious risks of local surface and groundwater pollution due to the wider environmental damage.

The resolution calls for States to closely cooperate in preventing, minimizing and mitigating the negative impacts of armed conflict or terrorism on the environment and participate in preparing national plans and strategies or setting priorities for environmental assessment and remediation projects, including better data collection for identifying health outcomes and ensuring that the data is integrated into health registries and risk education programs.

Though helpful in acknowledging these concerns over conflict pollution and the wider environmental and related health risks, States should put their money where their mouth is, as currently there is no comprehensive work undertaken to identify this program. Over the course of the last three years, PAX has used open-source research to start identifying the most visible or reported problems on conflict pollution through our reports and our work with Bellingcat. However, this type of work of conflict pollution identification needs to be done thoroughly with all relevant expertise from toxicologists, geology and environmental expertise, medical experts, industrial know-how on chemicals and through the inclusion of communities in identifying pollution and setting priorities for reconstruction, as well as setting up wider risk education programs.

Rebuilding Syria should include a strong environmental component to prevent civilian exposure to toxic remnants of war. States could support the UN Environment’s Disasters and Conflict Branch with funding and expertise to undertake a post-conflict environmental assessment, and support relevant civil-society groups to provide input the process of identification of conflict pollution. Furthermore, timely acknowledgement of the role of control over natural resources in this area also could play a role in conflict resolution, as there has been past and ongoing disputes over access to oil fields. This would also need to have a strong environmental component, as the past six years have affected local agricultural lands, caused water pollution and exposed many civilians to hazardous substances. PAX and the Conflict & Environment Observatory provided list of recommendations to States for implementing the resolution, whichi is scheduled to be discussed at UNEA-4 early 2019.

This blog, and other blogs for Bellingcat on this topic of open-source research is only a small attempt to demonstrate that much more work can be undertaken to identify conflict pollution and improve humanitarian response and post-conflict reconstruction work. Bellingcat and PAX therefore have provided workshops and training to UN agencies and humanitarian organisations during the UN Environmental Emergencies Forum in Nairobi in 2017 and the Humanitarian Partnership and Network Week in Geneva in January 2018. As noted by Jesper Lund, Chief of UN OCHA’s Emergencies Branch, “We can learn from the possibilities of using open-source as they can be used in humanitarian and emergencies environment to understand what is there and what is the effect on the local communities, but more important is their [open-source researchers: WZ] drive. They can’t be on the ground but they are sitting in their house and make a difference from there”. Yet in the end, it’s a state responsibility for the way they wage wars, what they target, and how much effort they put in limiting the effects of conflict on the local environment and health, and the responsibility of the international community to ensure the environmental dimension is included in a wider humanitarian response to armed conflicts.

I would like to thank Twitter user @obretix and Matthew Reed @MatthewMreed for support with analysis of some of the imagery