A War of Flags Between Guyana and Venezuela

On December 3, Venezuela held a controversial referendum over a claim to the oil-rich Essequibo region controlled by Guyana. That same day, the Vice President of Venezuela, Delcy Rodríguez, shared a video on X, formerly Twitter, showing a group of Indigenous people lowering a Guyanese flag and hoisting a Venezuelan flag in its stead over the territory, which is also known as Guayana Esequiba. ‘Glory to the brave people!’ she wrote, which is the first line of the country’s national anthem.

The post came after Guyana’s president Irfaan Ali made his own on November 24, in this case featuring a video in which he is shown attending the raising of a Guyanese flag at a purported border site between Guyana and Venezuela. Bellingcat was first alerted to the posts by EsPaja, a Caracas-based fact checking outlet. You can read their analysis of the same incidents here, in Spanish.

Venezuela has claimed Essequibo, which comprises two-thirds of Guyana’s territory, since the 19th century and the country’s president, Nicolás Maduro, has been accused of inflaming the issue to garner popular support as he gears up for a reelection campaign next year. (The Venezuelan government has moved to ban opposition leaders from running against him).

Tensions have risen in recent weeks over Essequibo, with Brazil moving troops to its northern border and the US announcing joint military drills with Guyana. As the raising and lowering of flags can indicate changes in territorial control, claims and counterclaims about these two videos have circulated online.

A popular interpretation among some Venezuelan and Latin American social media users is that the people in the video Rodríguez posted had removed the same flag hoisted by the Guyanese President in November.

Bellingcat has been able to geolocate both videos in this remote jungle area of South America. They actually show two different flagpoles located some 185 kilometres apart. While a Guyanese flag was lowered by indigenous Venezuelans, this event took place some 80 kilometres away from the disputed border with Guyana and roughly 20 kilometres from Venezuela’s border with Brazil. Why a Guyanese flag was flying there in the first place remains unknown.

Raising the Guyanese Flag

In the video posted by Ali, the Guyanese president, he arrives by helicopter at a mountaintop in the jungle. A group of soldiers salute as the country’s standard, also known as the Golden Arrowhead, is raised atop the flagpole. The president shared this video, which we’ll refer to as Video One, on his Facebook page on November 24.

He added that the flag was raised ‘more than 2,200 feet above sea level on our border’. Some flat, distinctive mountain ridges can be seen in the distance behind him. These are the Tepuis, which is the name of the table-top mesas and mountains common in western Guyana and Venezuela in the language of the indigenous Pemón people.

While analysing claims about the location of these events, Bellingcat researchers came across the same video posted to the Facebook page of the People’s Progressive Party, which Ali represents. It appeared 39 minutes after the president shared the video and was captioned ‘the Golden Arrowhead was hoisted atop Pakarampa Mountain this morning’.

A still from this video, showing soldiers posing with a large Guyanese flag, was earlier this month uploaded to the Google Maps location for Pakarampa Mountain.

However, the actual location was not on Pakarampa Mountain itself but can instead be traced to a nearby vantage point at (6.35919,-61.13761). The flag was indeed raised just inside Guyanese territory, east of the Wenamu River which forms part of the border with Venezuela. The camera faced east, showing Guyana’s Essequibo region.

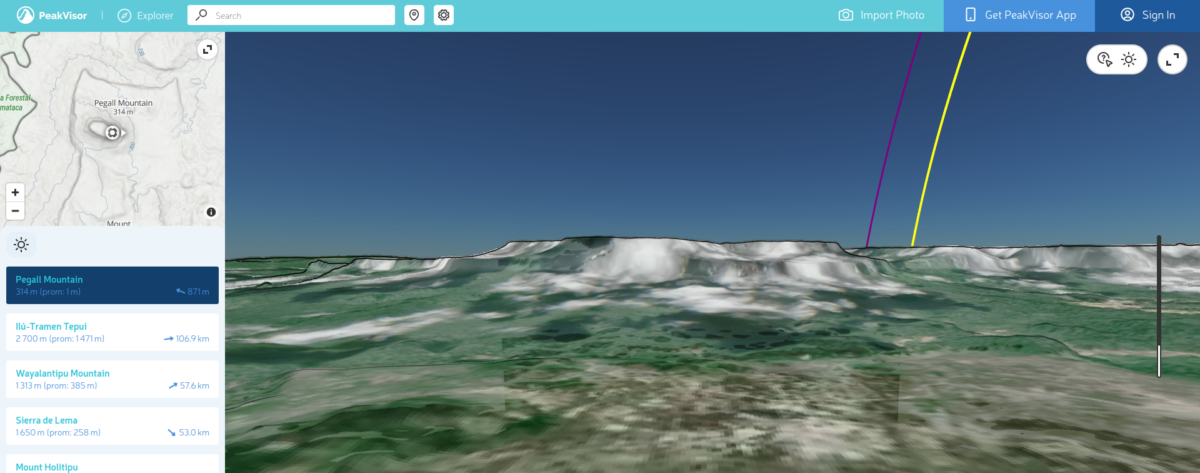

The scene of the soldiers posing with the flag is particularly useful given the mountain ridge in the background. Using a screenshot of the same scene – though not the same still as uploaded to Google Maps – yielded useful clues. The location was verified using PeakVisor, an app initially developed for mountaineers (you can read more about its usefulness for open source researchers here).

Here, PeakVisor displays the a virtual landscape of same mountain ridge as seen in Video One:

By overlaying the silhouettes of this mountain range to a still from Video One, we can see that they fit together. There are slight discrepancies due to difficulties matching the horizontal field of view (hfov) on the image overlay, but none significant enough to affect the match.

On December 11, journalists from AFP visited the village of Arau and reported that locals approved of Ali’s raising of the national flag over the nearby mountain, which the publication did not name.

Raising the Venezuelan Flag

A group of Indigenous people march toward a flagpole holding a large Venezuelan flag. In the following scene, a man declares the third of December ‘an historic day’ and that, in Essequibo, ‘this land is indivisible’.

Around him stand a group of people wearing T-shirts bearing an enlarged silhouette map of Venezuela including Guyana’s Essequibo region. While the text is not legible due to the poor quality of the video, the colours within the silhouette resemble the logo of the ‘Venezuela Toda!’ campaign which advocated for a ‘yes’ vote in the December 3 referendum.

This video, which we’ll refer to as Video Two, was shared on December 3 by Venezuelan vice president Rodríguez on X. El País reported that the video was released by the country’s Ministry of Communication — two Venezuelan cabinet ministers and the president of the national assembly posted the video on X, and all three posts were then retweeted by the ministry.

Geolocating Video Two was a greater challenge, due to the poor video quality and the size of the area which had to be covered in a manual search of satellite imagery for matching features. Starting with areas near the border between Venezuela and Guyana did not lead to a successful geolocation.

One Bellingcat Discord member suggested expanding our search area further, referring to a Telesur report which claimed that the flag-raising ceremony had been filmed in the Sierra da Paracaima mountain range and that the attendees were indigenous Pemón people from the area near the town of Santa Elena de Uairén.

The following X post also suggested that Video Two was filmed in the Paracaima mountains, although the user baselessly claims that the Guyanese President had raised a flag here.

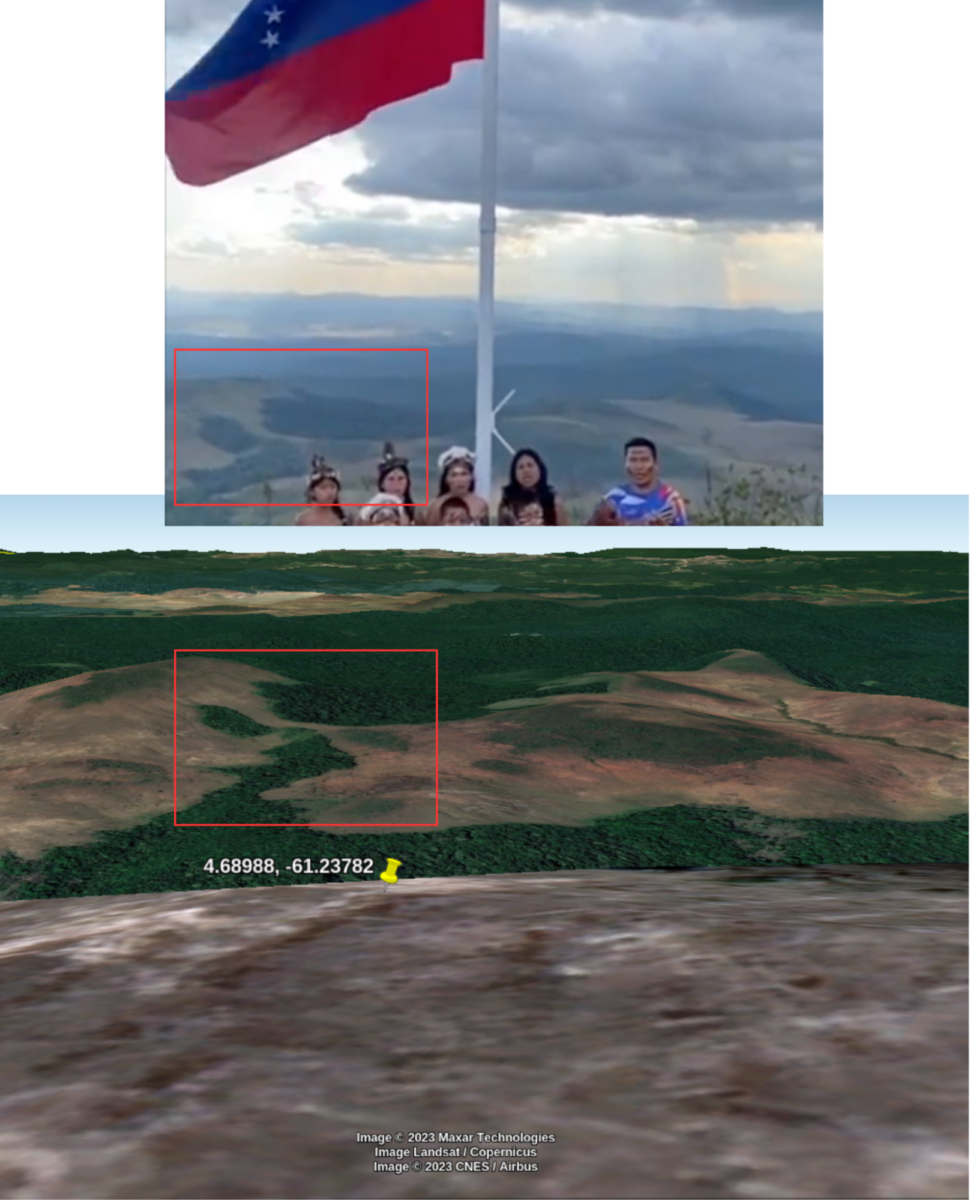

A search for matching features on satellite imagery near Santa Elena de Uairén yielded a match on Google Earth at (4.68988,-61.23782). A key detail was the shape of a patch of forested land in the distance. The camera faces south-west.

A Tale of Two Flagpoles

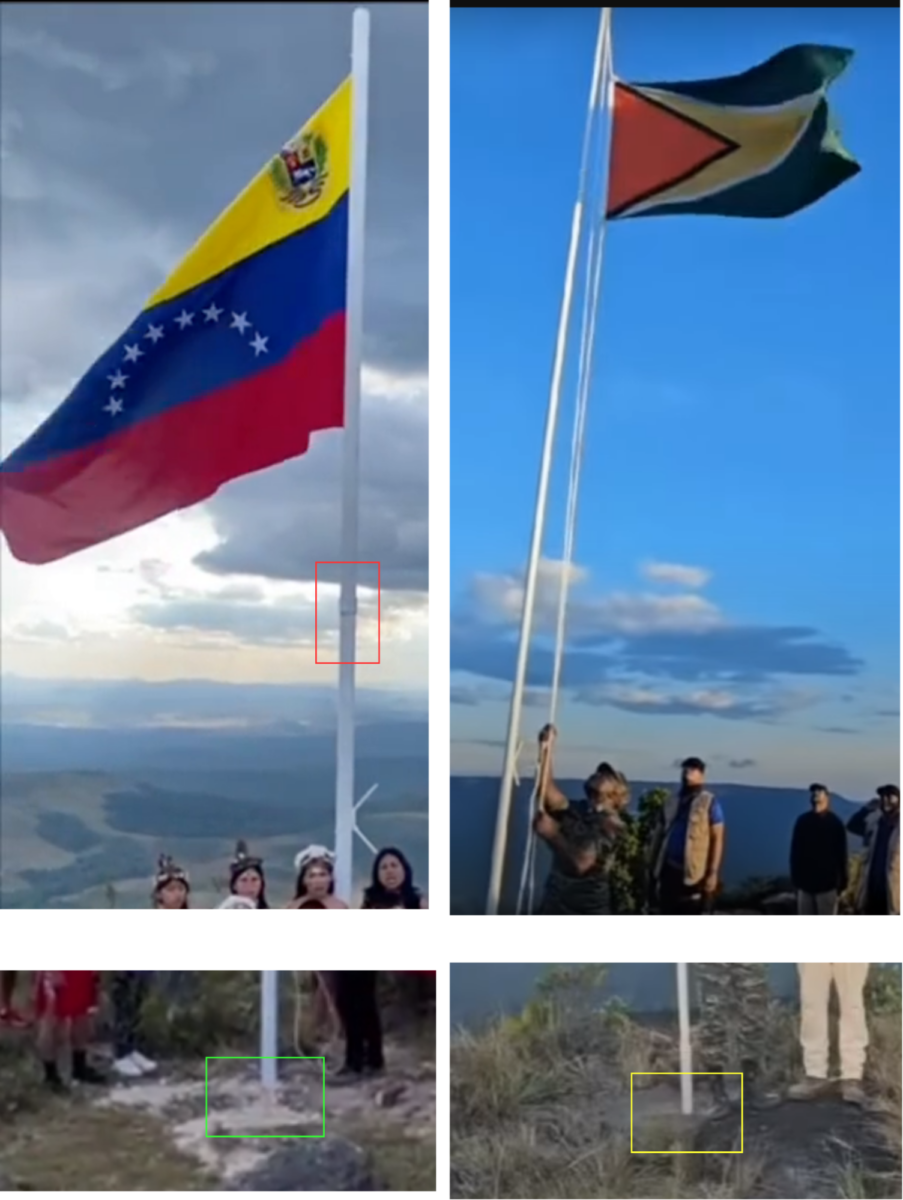

Despite similarities in the two videos, the claim that they show the same location does not accord with the available open source evidence. Not only are there differences in the surrounding landscape, but the flagpoles also appear distinct upon closer inspection.

For example, a joining element can be seen on the flagpole in Video Two. No such element can be seen on the flagpole in Video One. The Guyanese flagpole also appears taller and is affixed to a solid concrete base.

On December 3, the Guyanese news website Demerara Waves published an article on the flag controversy in which the Guyana Defence Forces (GDF) described the Tweet by Rodríguez and Video Two as “misinformation”.

The GDF also said following the flag raising ceremony attended by President Ali, a golden plaque had been installed at the site. Demerara Waves also published a photo of the plaque, whose text states that the Guyanese flag was raised on November 23 on Mount Arau. This plaque is one of several features which cannot be seen in Video Two, although it was filmed after Video One.

In sum, Video Two was filmed approximately 185 kilometres away from the raising of the Guyanese flag as seen in Video One. Video Two was actually filmed far closer to the border of Brazil (17 km) than that of Guyana (80 km).

This location is inside Venezuela itself, not the Essequibo area of Guyana which Venezuela claims.

Although a Guyanese flag can be seen in Video Two, it is clearly not the same flag as that raised in the presence of President Ali. The lingering question therefore is not only who instructed this smaller Guyanese flag to be removed but who put it up in the first place – particularly in a location near the Brazilian border with no obvious relevance to the current dispute.

Editor’s Note: This piece was updated on December 14, 2023 to credit EsPaja, who first alerted Bellingcat researchers to the videos in this story.

Annique Mossou, Youri van der Weide and Giancarlo Fiorella contributed research. Thanks also to members of Bellingcat’s Discord Server for their suggestions during the research process.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Instagram here, X here and Mastodon here.