The Sound of Bullets: The Killing of Colombian Journalist Abelardo Liz

WARNING: This report contains references to a fatal shooting and footage, images and audio of the shooting that some readers might find distressing.

When journalist Abelardo Liz was shot during a confrontation between soldiers and protesters at a land rights demonstration in Colombia in August 2020 he did not immediately drop his camera or stop filming; he held on to it as he fell to the ground and then handed it to someone else so the filming could continue.

The sound of the bullets recorded by Abelardo and by others at the scene provides new clues about the fatal shooting.

The shooting lasted 67 seconds and when it ended three people had been shot, two fatally-including Abelardo.

Bellingcat and Cerosetenta have analysed the audio and video evidence, combined with autopsy and ballistic reports and soldiers’ testimonies and uncovered significant inconsistencies in the army’s account of events.

Key Findings:

- The bullet that killed Abelardo appears to have come from the side of the road where Colombian soldiers and other security forces were located.

- The bullet found in Abelardo’s body was consistent with the bullets and type of weapons carried by the platoon of soldiers that day.

- Soldiers fired their weapons into the ground at close range to civilians.

- Soldiers appear to have started the shooting.

- Although an exchange of fire can’t be ruled out, at no point are soldiers seen ducking for cover.

- We found no evidence that the army came under fire from the mountains.

These findings contradict sworn testimonies by members of the Águila 1 platoon about the events of August 13, 2020. They claimed that they fired at armed dissidents in the mountains in response to an attack and did not fire dissuasive shots near civilians. The Águila 1 platoon is part of the High Mountain Battalion Number 8 of the Third Division Of the Colombian Army, the platoon was under the command of Sergeant (Sargento Viceprimero) Carlos Álvarez Rodríguez on that day, according to a sworn statement made by Álvarez Rodríguez. Another platoon was also present. In a statement released immediately after the incident Brigadier General Marco Mayorga, commander of the Third Division, said: “It should be noted that the soldiers from the Colombian Army never fired their weapons at the indigenous community.”

Bellingcat and Cerosetenta contacted the army several times and put our findings to them. In response the commander of the High Mountain Battalion No. 8, Lieutenant Colonel Jorge Armando Rojas told us that troops acted correctly and were supporting the national police and anti-riot squad when they were “interrupted by illegal armed groups, which, carrying out flagrant violations against International Humanitarian Law and human rights they shot against the troops present and the civilian population.” He said they were unable to share operational details about any alleged militants involved in the shooting. He said a disciplinary investigation into what happened that day had been carried out by the battalion and closed after it found no evidence of disciplinary offences by any of the soldiers.

Watch Cerosetenta’s video on Abelardo’s case and read more about the background and audio analysis below.

Colombia, Cauca and the Nasa Indigenous People

Abelardo joins a list of at least fifty two journalists killed in Colombia since 1993 according to Unesco’s Observatory of Killed Journalists. Abelardo was an indigenous journalist working for radio station Nación Nasa Estéreo and belonged to the Communications Network of the Indigenous Council of Corinto when he was shot.

The Nasa indigenous people have been engaging in what they call “Liberación de la Madre Tierra” – a process through which Nasa people are occupying territory which they say have been taken away from them since Spanish colonisation.

Typically, land in the Cauca region has been concentrated in the hands of agribusinesses. As a consequence, Nasa people have been historically displaced to areas not ideal for agriculture, limiting their ability to sustain themselves.

According to a report in Revista Estudios Socio-Jurídicos journal, this has pushed their tactics to occupy land to debatable legal limits which has created tensions in the region.

Nasa community members have also reportedly been caught up in territorial conflict between narcotraffic cartels, dissidents from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) , the Colombian military and police and other armed groups in the area. This has led to deaths of Nasa community members.

How Events Unfolded on August 13

Colombian police and anti-riot police squads were tasked with evicting an indigenous Nasa community who had occupied the Quebrada seca hacienda located near Corinto.

Colombian soldiers were at the perimeter of the operation because of the possible presence of FARC dissidents in the area. The army had exchanged fire with FARC dissidents approximately 4km from the site the day prior.

Abelardo, who can be seen in a yellow t-shirt and black backpack, was covering the eviction and filming with a hand-held camera.

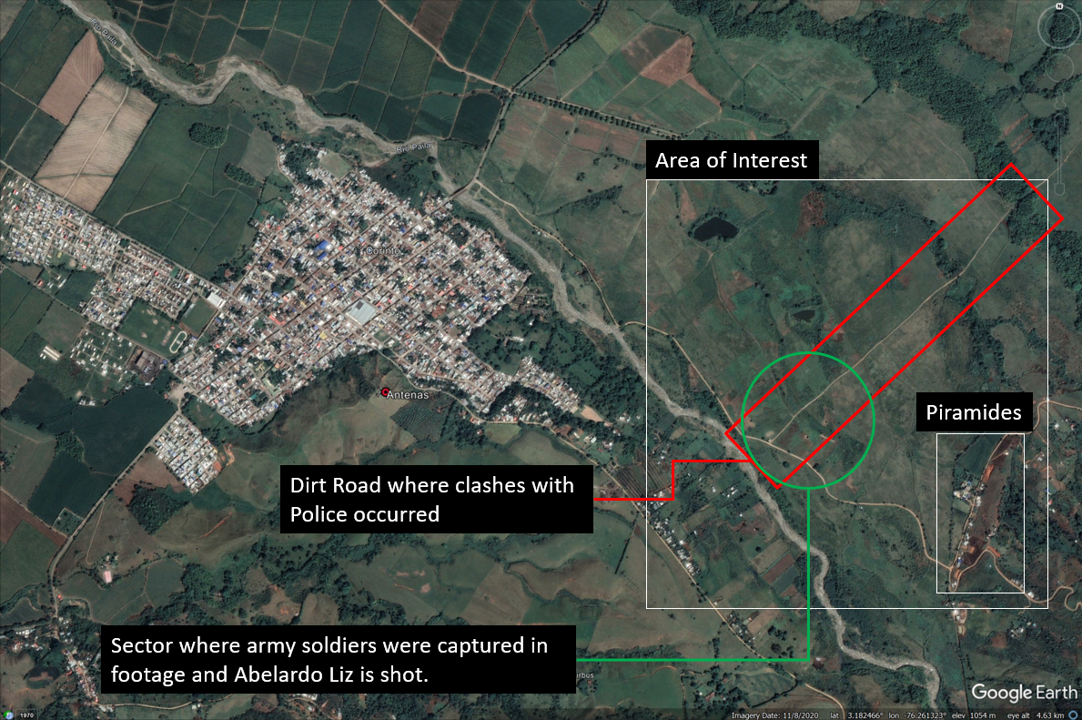

Prior to the shooting protesters and police were involved in a series of clashes along the road leading away from the plantation, highlighted below. The road is located 1.8 kilometres east of Corinto, here (3.17034, -76.2449).

Around noon the eviction operation ended and 21 members of the Águila 1 platoon descended from the nearby Las Piramides mountains.

According to the soldiers’ statements they were diverted into the corn crops after approximately 50 indigenous protesters blocked their passage, around here (3.168272, -76.244601). There is no video record to substantiate these claims.

From this point, footage recorded shows the platoon marching among the protesters.

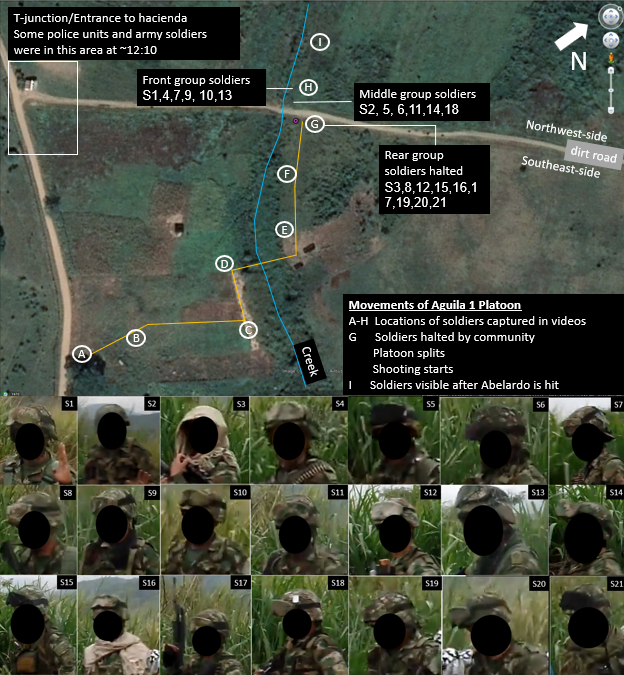

Analysing available video evidence we determined the approximate route the soldiers followed until they arrived at the dirt road where Abelardo was fatally shot. These videos show that along the path, the soldiers from Águila 1 were followed by agitated protesters who shoved and insulted the soldiers while demanding them to leave the premises.

We were able to track the location of these soldiers before, during and after the shooting of Abelardo by identifying details on their uniforms and the type of weapons they carried. All their names and faces have been blurred to protect their identities.

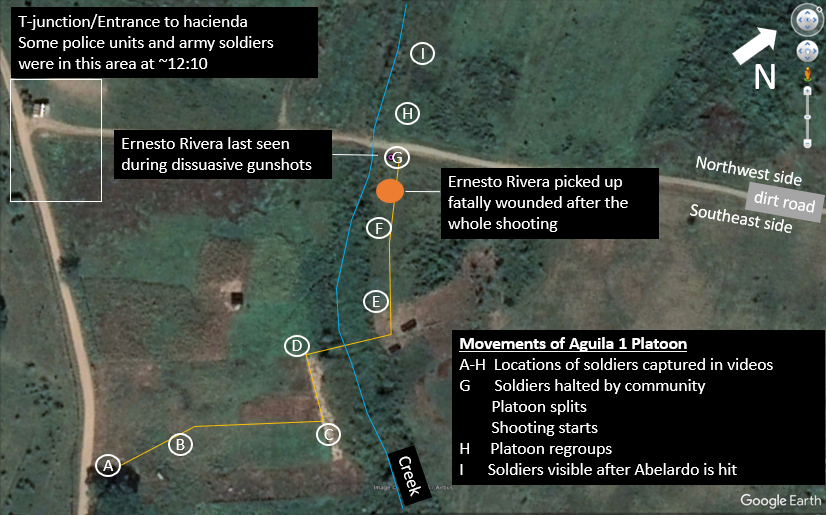

As members of the Águila 1 platoon marched to position G (highlighted below), another group of police and soldiers were also positioned at the T-junction located at the entrance of the hacienda.

At about 12:10pm the shooting started.

What Audio Analysis Can Tell Us About the Shooting

Bellingcat and Cerosetenta analysed 118 videos filmed on August 13; 16 of which were recorded during the 67 seconds the shooting lasted. Bellingcat has previously used audio forensic analysis to investigate The Killing of Muhammad Gulzar and Unravelling the Killing of Shireen Abu Akleh and compare the sound of live rounds against witness testimonies and official statements.

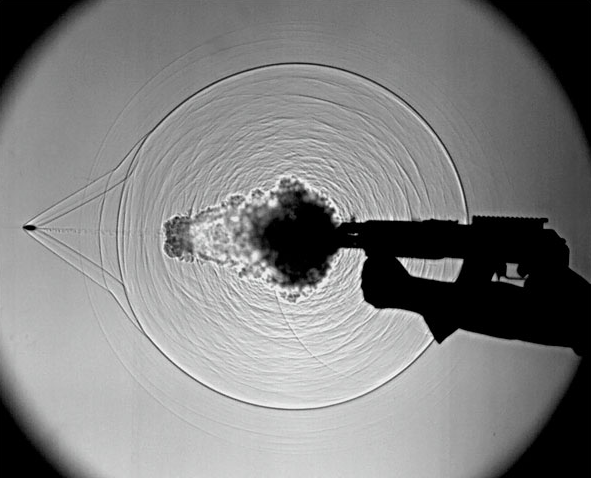

When bullets are fired there is a “bang” made by the propellant combusting in the bullet cartridge as it leaves the barrel of the gun. This sound travels at the speed of sound through the air.

However, most rifle ammunition available is supersonic.

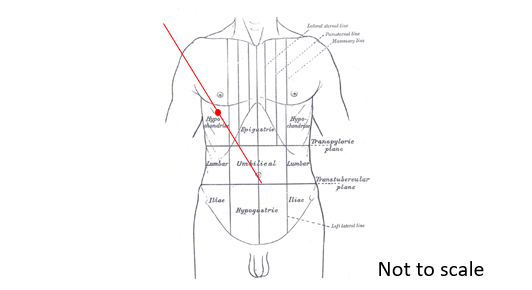

When supersonic rounds are fired, the first thing heard by a person in the line of fire is the shockwave (crack) caused by the passing bullet followed by the respective muzzle blasts (bang). See the diagram below.

Because a supersonic bullet travels faster than the muzzle blasts, there is a time difference between the arrival of the crack and the arrival of the bang sound to the microphone recording the shooting.

Here is an example from a video filmed during the shooting on August 13. You can hear the crack sounds typical of that made by supersonic bullets- followed by a muzzle blast:

Audio forensic experts use this time difference to identify live rounds, estimate the distance of a shooter and understand more about a shooting.

According to Dr Robert Maher, Professor of Electrical & Computer Engineering at the State University of Montana, multiple recordings of a shooting may provide useful information about the location and orientation of the firearm, whether or not multiple guns were present and who fired the first shot.

A method called multilateration may allow the localisation of a sound source by analysing multiple recordings and measuring the time difference of arrival of the sound waves to each of the respective microphones.

Using the shooting patterns identified and other visual and audio references contained in the videos, we geolocated and synchronised all the audio material. The resulting sequence showed that the shooting lasted a total of sixty seven seconds, you can watch it here:

We grouped the audio segments containing the same shooting patterns and organised the data from August 13 by shooting episodes and shared it separately with audio forensic experts Steven Beck from Beck Audio Forensics and Dr Robert Maher from Montana State University.

Tensions Escalate and Shooting Starts at 0:00

After their diversion through the corn crops, the Águila 1 platoon reached the dirt road. At this point some of them were intercepted by protesters and the platoon was forced to split up. Twelve of the platoon managed to cross the road but nine were fenced in by the crowd. The Águila 1 platoon had now been separated into two groups. Here’s a reminder of the positions.

Tensions escalated as some members of the indigenous community seemed to threaten the soldiers with machetes; one appeared to steal a large knife from a soldier. Another man grabbed the end of a soldier’s rifle and struggled with him. Moments later the shooting starts.

Footage shows some of the protesters look towards the soldiers located on the northwest side of the road as soon as the shooting starts. Some people also appear to run away from the road. This could be an indication of the possible origin of the first shots.

From the northwest side of the road the twelve soldiers appear to signal to the rest of the soldiers to cross the road. As seen in the image below, at least eight soldiers do not seem to seek cover as the shooting continues.

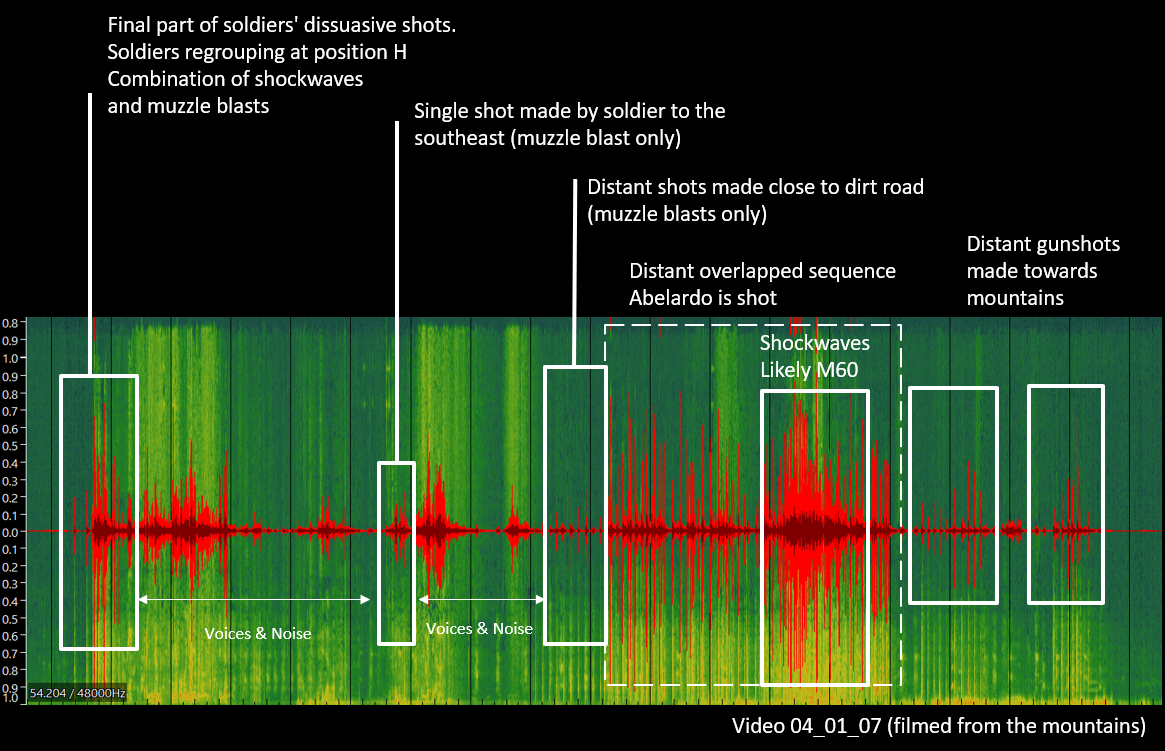

Audio forensic expert Steven Beck reviewed the footage and audio material and outlined that the first round of gunshots recorded in the videos seem to have been initiated by a fully automatic gun with a frequency of shots corresponding to an M60, followed by the sound of Galil rifle shots.

You can listen to the audio sequence from the start of the shooting here:

Case files seen by Bellingcat and Cerosetenta show that machine guns M60s and Galil ACE 23 rifles were indeed carried by the Águila 1 platoon during the eviction operation on August 13, 2020. Separately, forensic evidence collected after the shooting at the site included 7.62 millimetre bullet casings and metal links compatible with machine guns such as M60s. Ballistic reports also stated that at least nineteen 5.56 millimetres bullets were fired by the army in the vicinity of where Abelardo was shot.

Visual analysis supports this, two of the soldiers, located on the northwest side of the dirt road when the shooting started, appeared to be carrying M-60s while the rest of the soldiers appeared to be equipped with Galil ACE 23.

Protesters Disperse and Next Round of Shots at 00:06

After the first shots were fired, the crowd continued to disperse; clouds of dust were still visible over the road. Soldiers who had been held on the southeast side of the road began to move towards the rest of the platoon in order to rejoin them.

During this time Abelardo filmed the soldiers as they crossed the road. It is from his camera and others nearby that we can hear the next series of shots.

At first the sound of live rounds- a combination of shockwaves (cracks) shortly followed by the corresponding muzzle blasts (bangs)- are clearly heard indicating that there were bullets travelling at supersonic speed and passing by the camera’s microphones.

After this, the shooting pattern evolves to a more overlapped series; amongst the gunshots we also hear very loud muzzle blasts without shockwaves.

You can listen to the shooting episode here:

According to both audio forensic experts Bellingcat consulted, the gunshots heard in the first three seconds of this audio section came from approximately 50-60m away from the dirt road. According to visual evidence, soldiers from Águila 1 were within this radius. However, we do not know the direction of travel of the bullets.

Although an exchange of fire can’t be ruled out, based on the audio data above, visual evidence shows that at least thirteen soldiers out of 21 in the immediate vicinity of the dirt road do not appear to seek cover.

Footage also appears to show several soldiers shooting into the ground in very close proximity to civilians – also known as ‘dissuasive’ shots. This could explain the very loud gunshots or muzzle blasts which did not exhibit shockwaves during the rest of the above audio sequence.

According to Dr Robert Maher:

“This could be due to shots being directed at the ground [where] the bullet stops relatively close to the firearm, and does not travel through the air past the microphone”

Dust puffs are also visible on the dirt road, suggesting bullets were indeed hitting the ground. At least four soldiers were captured by Abelado’s camera firing shots semi-horizontally or into the ground.

This audio contains some of the last shots made into the ground before the platoon started to move further away from the dirt road (towards position “I”). The same shots can also be heard in a video recorded in the Las Piramides sector in the mountains. We will discuss the importance of this later in the text.

A number of the soldiers from Águila 1 platoon seen shooting into the ground gave statements at an internal disciplinary procedure in the days after the incident and denied firing dissuasive shots

The case files of the internal disciplinary procedure seen by Bellingcat and Cerosetenta state that soldiers denied firing any dissuasive shots at the indigenous community. Instead they claim to have only reacted to gunfire received from the mountains.

The case files of the internal disciplinary procedure seen by Bellingcat and Cerosetenta state that soldiers denied firing any dissuasive shots at the indigenous community. Instead they claim to have only reacted to gunfire received from the mountains.

The person conducting the hearing asked:

Could you please inform this committee whether you or any other soldier fired dissuasive gunshots as a consequence of the aggressions received from the indigenous community?

One soldier answered:

“No, I never gave the order to fire any dissuasive gunshot like shooting in the air or into the ground”

Another soldier answered:

“No, there were no gunshots fired as a consequence of the aggressions received from the indigenous community. We always repelled the attack towards the mountains from which we were attacked”

However, all available evidence examined by Bellingcat and Cerosetenta appears to indicate the platoon was not under enemy fire from the mountain sector located approximately 800 metres away.

A First Shooting Victim?

Three people (Abelardo Liz, Ernesto Rivera and Julio César Tumbo) were injured on August 13, 2020; two of them fatally.

Towards the end of the dissuasive shots, as the whole platoon reunited and was moving away from the dirt road a person shouted in Spanish “Este está herido herido! Este está herido!” (This man is wounded! This man is wounded!)

Precisely at this moment, Abelardo can still be seen in footage – he can be identified by his yellow t-shirt and he can be seen continuing to record events. He is standing next to Julio César Tumbo. Both men were still uninjured at this time.

After the whole shooting ended, visual evidence shows that a man- presumably Ernesto Rivera- is seen lying down, a few metres away from where he was seen standing in earlier footage.

Based on visual evidence, it is plausible that Ernesto Rivera could have been shot and injured during this period of shooting just before soldiers regrouped on the northwest side of the dirt road. However, further investigations are needed to verify the identity of the wounded person and how he was wounded.

We put all this evidence to Morris Tidball-Binz UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions. He told Bellingcat and Cerosetenta that:

“The soldiers acted outside the norms and parameters established by the standards for the use of force by law enforcement officials, including the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (1990). With this, they violated the requirements of legality, necessity, proportionality, precaution and responsibility, including, for example, using highly lethal weapons of war to disperse a demonstration.”

It is unclear why the soldiers denied having fired dissuasive shots at the indigenous protesters on August 13, 2020; but it raises questions as to what really happened and what level of training the platoon had received to manage such situations.

A Single Bullet and Brief Break in Gunshots 00:26

When all 21 soldiers had regrouped on the northwest side of the dirt road, they retreated away from the protestors along a creek, here’s a reminder of the positions.

As they retreated, a single gunshot was fired, which appears to correspond to footage showing a small flash amongst the soldiers. The sound was also picked up by several different video recordings. You can listen to audio of the gunshot recorded by a camera located near position “G” close to Abelardo.

We also identified a small flash which appears to be the release of muzzle gases, in footage filmed near position “G” and Abelardo. The gunshot heard in the audio coincides with the small flash seen on camera.

Apart from this bullet, no other gunshot sounds appear to have been recorded for a total of seventeen seconds- suggesting soldiers were not under fire during this time.

Shooting Resumes at 00:43

A series of shots heard after the brief pause in shooting merits further investigation.

The sound of these eleven gunshots were picked by six cameras. You can listen to these audios in the interactive map below.

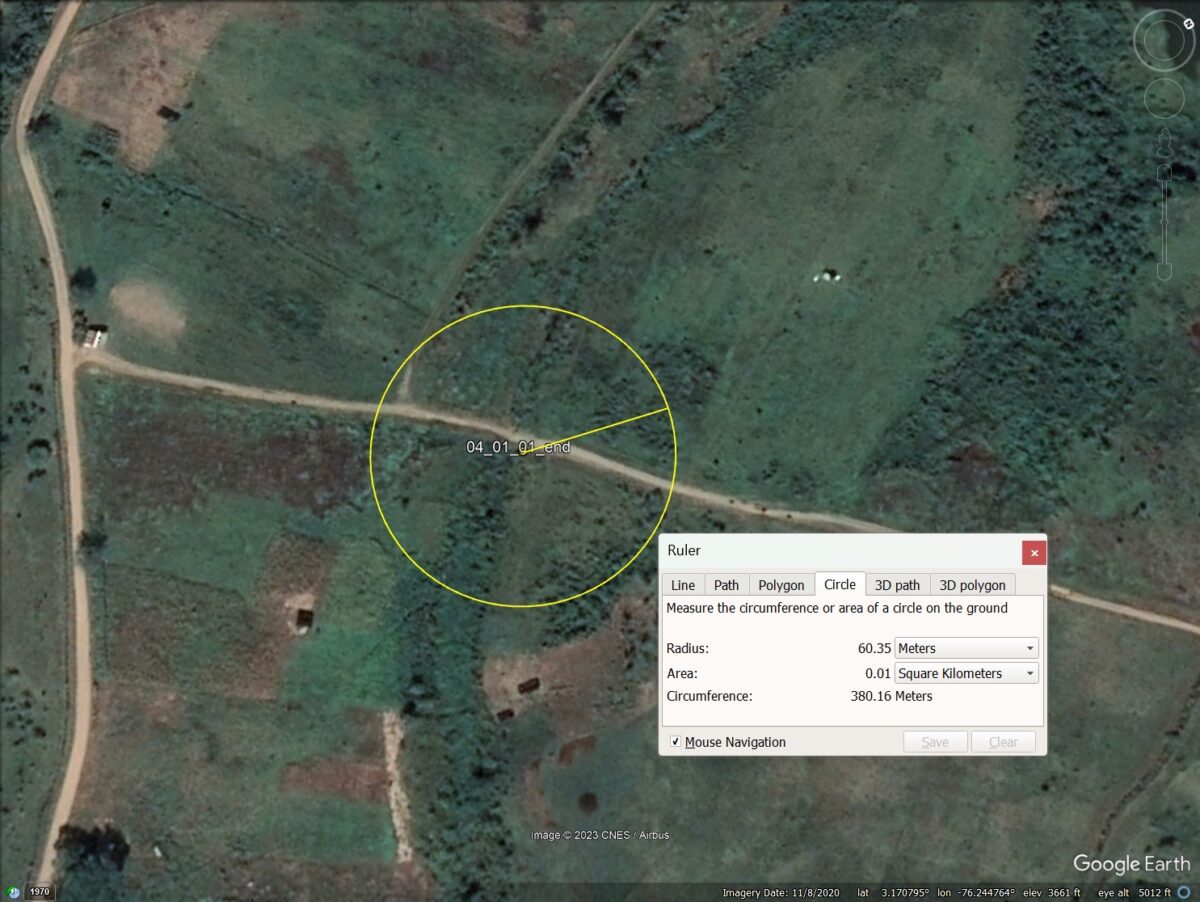

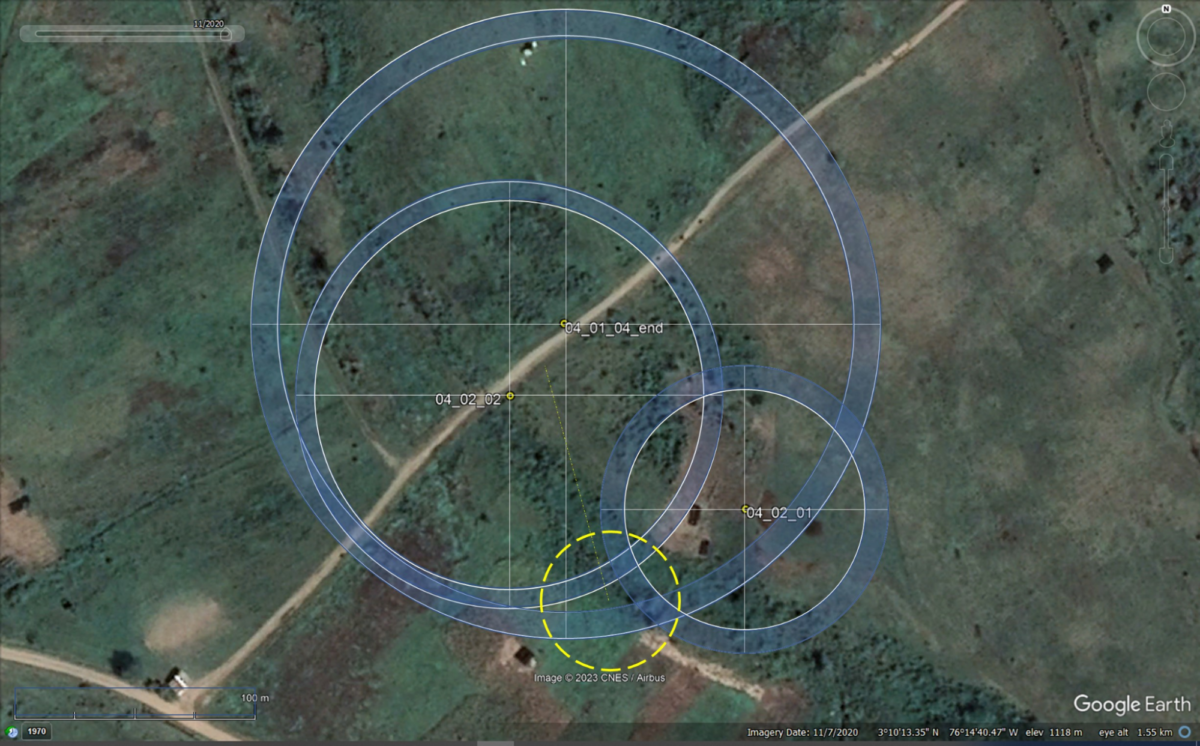

Where available, audio forensic experts Dr Robert Maher and Steven Beck used the time difference between the arrival of the shockwaves and the respective muzzle blasts to estimate the distance each camera was from the shooter. Both experts arrived at very similar conclusions – suggesting a possible shooter located at the following site highlighted in yellow in the diagram below. However, a number of factors including that we do not know the exact speed of the bullets, nor do we know their exact trajectory- causes some uncertainty. The location below is just an estimate.

Dr Maher explains the results which we have displayed on the diagram below:

“This result is depicted in the Google Earth picture below, with the blue circles indicating the approximate range of distances. Theoretically, the three circles would share a common locus representing the likely shooting position. In this case, the timing results do not depict a singular solution, but the ranges do come closest in the region where I show the yellow dashed circle.”

We also noticed that shockwaves were only featured in videos recorded north of the yellow circle. The recordings made to the south-southeast, including the video filmed in the mountains, do not seem to feature shockwaves which could be an indication that these bullets were likely shot towards the dirt road.

According to the evidence presented in this section, an exchange of fire cannot be ruled out. The area was occupied by the indigenous community during the shooting. However, Bellingcat and Cerosetenta have seen no evidence that anyone within the indigenous community was armed with guns, nor did we see any visual evidence of security forces in this area. Without this material to complement the sound of the bullets, it is impossible to know who fired these shots.

Although the location of the shooter is just an estimate, what the analysis shows is that these series of gunshots were most likely fired closer to the dirt road and not from the mountains. Further investigation is needed to establish their exact origin.

Final Series of Shots at 00:47 – Abelardo is Shot

The shots analysed in the previous section transitioned to another sequence where there is a significant increase in the number of gunshots fired.

Amid the chaos, Abelardo keeps filming up until the moment he is shot and falls to the ground. We know from his own recording that after being hit he managed to pass his camera to a man close by so the filming could continue. After Abelardo is shot, two final rounds of gunshots are heard. People run to assist Abelardo and Julio who are both wounded.

Watch the videos below to see the moment Abelardo is shot. WARNING: You may find the content of the videos distressing.

As Abelardo filmed the moment he was hit, we used this exact moment recorded on his camera to synchronise all the footage we analysed.

What Direction did the Bullet come from?

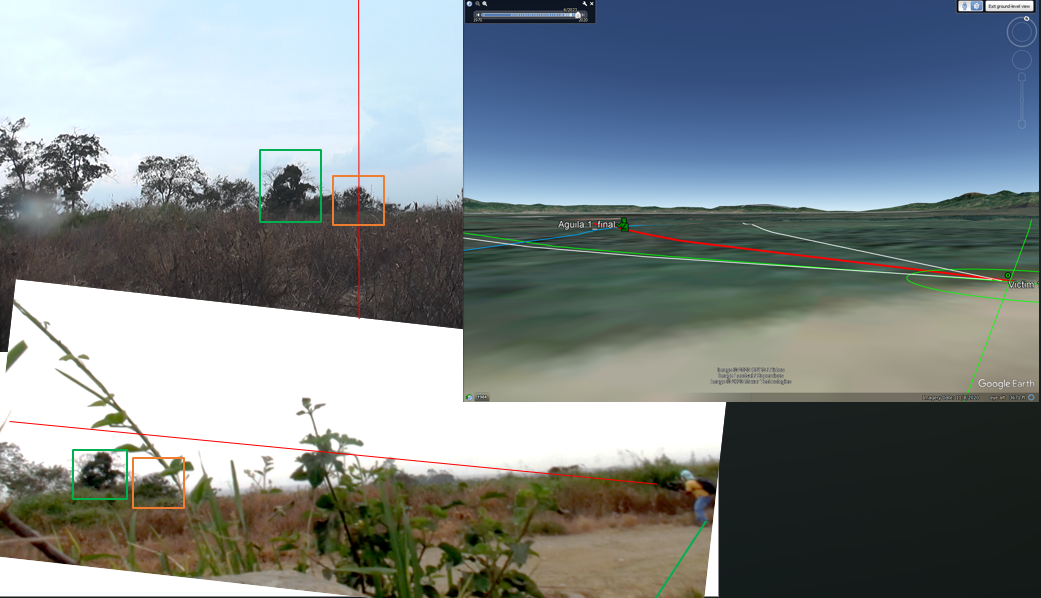

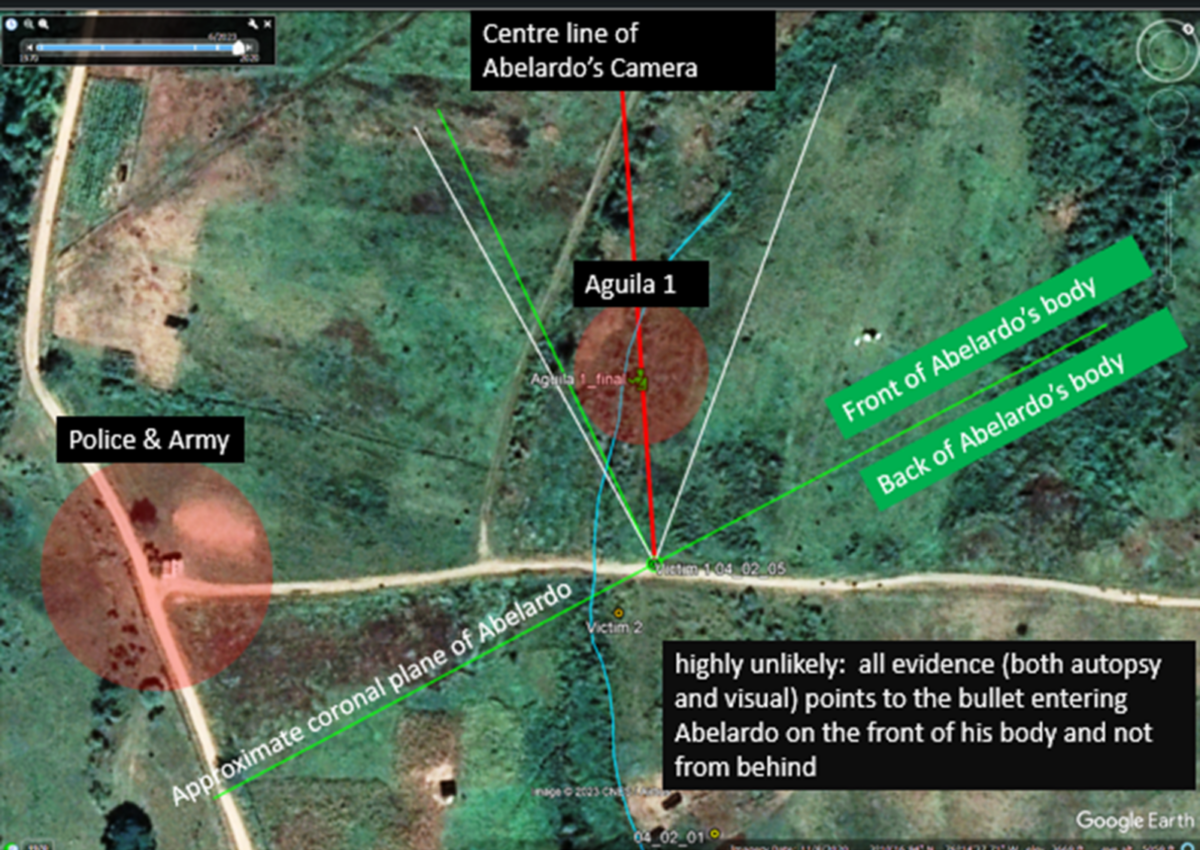

Abelardo’s position was determined by overlapping and triangulating different videos and comparing these to terrain features using PeakVisor and Google Earth.

Abelardo was filming the incident with his own camera. His video shows the approximate direction his camera was facing when he was shot. Synchronising this material with other videos, we can estimate the relative position of his body with respect to the road.

Visual information, including that collected by Abelardo himself, shows that he was pointing his camera towards the soldiers- who were located at position “I”– and he was crouching slightly, seconds before he was hit.

One of the soldiers in the platoon who wore a distinctive head cover allowed us to triangulate and identify the position of the platoon seconds before, during and after Abelardo was shot.

Abelardo’s autopsy, seen by Bellingcat and Cerosetenta, shows the bullet entered Abelardo’s body through his right side between his ribs and descended from right to left until it lodged in one of his last vertebrae. Visual evidence shows the bullet entered Abelardo on his front, right side.

All available evidence appears to indicate- the bullet that killed Abelardo Liz came from the northwest side of the road where the soldiers from Águila 1 platoon, as well as other soldiers and members of the police and ESMAD were located. There is no evidence of any other actor, besides these security forces located on the northwest side of the road.

The fact that Abelardo was shot in the upper abdomen and was facing northwest makes it highly improbable that the bullet that killed Abelardo came from behind him or from the mountains.

The diagram below outlines Abelardo’s position relative to the soldiers and other security forces at the time he was shot.

Abelardo’s autopsy stated that a 5.56 millimetre bullet was recovered from his body. The 5.56 millimetre bullet is compatible with rifles such as the Galil ACE 23. However, the forensic team couldn’t determine whether or not it came from any of the weapons carried by soldiers that day. Citing that there were not enough microscopic marks or striations on the bullet to establish who shot Abelardo.

Shots Heard in Las Piramides Sector

During the period that Abelardo was shot, the sound of the bullets were highly overlapped making it difficult to analyse. However, it still provides some important information – primarily that we can find no evidence of shots being fired from the mountain area towards Abelardo and the soldiers.

After listening to the sound of bullets that were highly overlapped, audio expert Steven Beck explained there is a rapid sequence of nearby gunshots during this period that is consistent with an M60.

Shockwaves associated with these rapid shots were heard in the videos filmed in the mountains too. This indicates that the M60 was likely aiming in that direction.

Moments before and after Abelardo was hit, we can see bullets hitting the ground around him. This appears to confirm that some of the gunshots were being aimed at this area of the dirt road.

After comparing the data from different videos Dr Robert Maher concluded that the final two rounds, fired after Abelardo was shot, are gunshots consistent with a shooter aiming towards the mountains. We can hear those two final rounds, seconds 5 to 13, in this video posted by the army.

In order to further examine the army’s claim that they received fire from the mountains – and were shooting in response to this, we took all the video and audio data available from the whole gunshot sequence (67 seconds) and compared it with the video recorded in the area the army claimed they received fire from (marked in red, on this map). The distance between the camera and the dirt road was approximately 800 metres. You can watch the video here:

We found that this video recorded in the Las Piramides sector contains the last 40 seconds of the total 67 seconds of shooting.

Although we only have one camera recording in Las Piramides sector, the evidence from this recording indicates there seemed to be no one shooting in this area – however this can not be ruled out completely.

The majority of the distant muzzle blasts heard in the video filmed in the mountains appear to correspond to gunshots fired near cameras closer to the dirt road where Abelardo was hit- away from Las Piramides sector. We have outlined all these shooting episodes above.

According to the experts we spoke to, there seems to be some instances of supersonic shockwaves associated with bullets most likely travelling towards the mountain and passing by this camera.

Although the audio evidence is limited, there are other aspects to consider.

Las Piramides sector is located approximately 800m from where Abelardo was shot.

Morris Tidball-Binz told Bellingcat and Cerosetenta that 5.56 mm calibre bullets, which were used by the army on the day and recovered from Abelardo’s body, are usually used against targets between 200 and 400 metres away. Shooting at targets beyond 600 metres reduces their effectiveness and reliability. Instead, the wound and nature of the injury suffered by Abelardo is compatible with a shot fired from a closer proximity to him.

The Army’s Response

After the shooting incident, Brigadier General Marco Mayorga commander of the Third Division of the Colombian Army gave an account of events and denied the soldiers shot towards indigenous community, stating.

“Some members of the community, acting outside of the law, charged against the public force when they were carrying out their constitutional duties and causing wounds to some soldiers.”

He claimed that after this, platoon soldiers received an attack from the high part of the hacienda.

“The attack was carried out by a dissident group.”

He continued:

“It should be noted that the soldiers from the Colombian Army never fired their weapons at the indigenous community. On the contrary,they responded to the attack from dissident groups against the troop without caring about the presence of civilians.”

It should be noted that the soldiers from the Colombian Army never fired their weapons at the indigenous community.

Brigadier General Marco Mayorga

Bellingcat and our partners Cerosetenta asked the army about the death of Abelardo and the army’s own internal investigation into the incident. We asked if the internal investigation was still open and if concluded what the verdict was and if anyone had been disciplined.

We also asked if the army stood by the version of events outlined publicly by Brigadier General Marco Mayorga on August 13, 2020 immediately after the incident and if the army had found out anything more about the armed actors that were allegedly involved.

In response the commander of the High Mountain Battalion No. 8, Lieutenant Colonel Jorge Armando Rojas told us:

“The troops of the High Mountain Battalion N 8 ‘Colonel José María Vezga’, who were in support on the day of the events, acted correctly in accordance with the constitutional mandate.”

He outlined that, the troops were “providing security to the personnel of the National Police and the Mobile Anti-Riot Squadron (ESMAD), who in the development of their work were interrupted by illegal armed groups, which, carrying out flagrant violations against International Humanitarian Law and human rights they shot against the troops present and the civilian population.”

He also stated that: No evidence of disciplinary offences by any of the soldiers was found in the internal investigation. The statements of Brigadier General Marco Mayorga are presumed true. The army is unable to share operational details about any alleged militants involved in the shooting.

Three Years On

Three years since the killing of Abelardo Liz no one has been held accountable for his death, despite the large quantity of evidence available. At least three members of the Águila 1 platoon who were present during the operation that killed Abelardo are currently being investigated in relation to the death of activist Flower Jain Trompeta Pavi in a separate military operation that occurred 10 months earlier in October 2019. The Colombian Prosecutor’s Office (Fiscalia) identified inconsistencies in soldiers’ accounts of events and questioned whether the platoon had adhered to the rules of the operation. No one has been convicted in the case which is ongoing.

Bellingcat and Cerosetenta contacted the Fiscalia about the two incidents involving the Águila 1 platoon. They told us respective investigations were being carried out into the Abelardo Liz and Flower Trompeta cases in line with the Fiscalia’s mandate.

Data Visualisation: Miguel Ramalho.

Material from The Communications Network of the Indigenous Council of Corinto/ Tejido de Comunicaciones del Cabildo Indígena de Corinto and Abelardo Liz.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Instagram here, X here and Mastodon here.