The Challenges of Conducting Open Source Research on China

The People’s Republic of China is well known for its efforts to restrict the free flow of information online. With this in mind, this guide provides an overview of some of the challenges facing open source researchers investigating China- focusing primarily on those outside China. For those who are just getting started in open source research on China, it is designed to give an idea of the difficulties you may face. Since 2017 evolving censorship tactics and increased regulations that reduce anonymity online have made open source research on China increasingly difficult. Methodologies that researchers have used successfully in the past are often rendered useless by new restrictions if Chinese authorities become aware of them. Access to Chinese websites and social media apps, as well as methods for investigating them, are therefore currently shrinking.

The current range of difficulties may sound bleak – and to a certain extent it is – but that doesn’t mean that people aren’t finding creative ways to work around them, or that there aren’t clear ways that developers and other researchers can work to improve things. To better understand the current situation, Bellingcat interviewed a dozen China researchers who specialise in tech or human rights, including in Xinjiang and Tibet, about the challenges they’re facing doing open source research on China.

Shrinking Access to the Chinese Web

In 2017, shortly after the mass detention campaign targeting Muslim minorities began in Xinjiang, it was still possible to find a lot of information about what was happening there on Chinese websites and social media platforms. Procurement notices showing bids for construction work in re-education camps were posted on government websites and could be archived by researchers; these documents often included valuable information such as the camp’s address. Images of opening ceremonies of factories – where forced labour was reported- were posted on social media platforms such as Weixin. In other, now deleted, social media posts Communist Party officials shared pictures of themselves living together with Uyghur families as part of the ‘Becoming Family’ program which Chinese authorities claim is designed to ‘foster ethnic harmony,’ but Human Rights Watch has described as violating rights to privacy and family life and the cultural rights of ethnic minorities. Xinjiang was a place that was effectively out of bounds to many journalists and researchers, but online sources were a rich source of information that enabled investigative work to be done.

Darren Byler, an anthropologist and Assistant Professor of International Studies at Simon Fraser University, has written extensively on the camps system in Xinjiang. He told Bellingcat that he has seen how censorship of this issue has evolved over the last few years in response to negative media coverage.

“It appears that there’s purging of documents related to the thing that was just published on… things related to the camp system, they were available until 2019 or so, and then they almost all have been erased.”

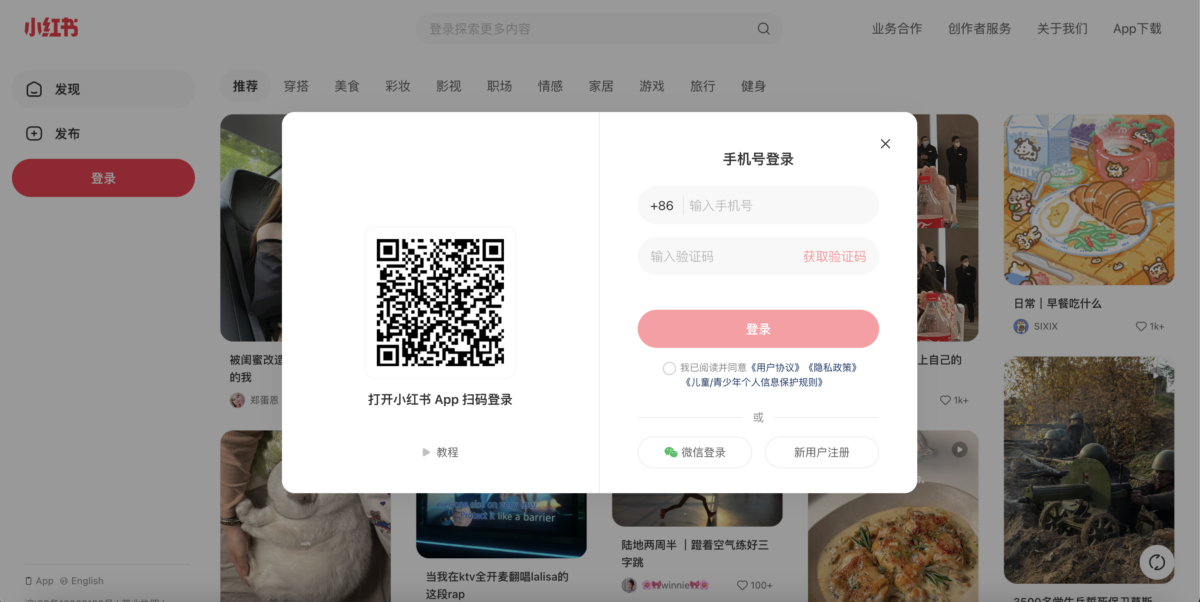

According to researchers Bellingcat spoke to, restrictions on information related to Xinjiang were slowly introduced from 2017 onwards. For example, researchers told Bellingcat that cotton trading websites and business registries have been an invaluable resource to investigate supply chains in Xinjiang but today, a search for the same information- a list of business registries in Xinjiang for instance – returns only a fraction of the previously available results. Bellingcat tried to access three of these (one business registry and two cotton trading websites) and we found a pop-up would sometimes appear, requiring you to login using a Chinese phone number. The issue with using a Chinese phone number to access information is discussed in more detail below.

Researchers told Bellingcat the restrictions extended beyond Xinjiang to other subjects and information considered sensitive. They also outlined that in some cases posts and websites remain accessible within China, but have become more difficult to access from outside the country and restrictions continue to grow. Wider curbs that would further limit external access to Chinese information and databases have also been proposed; in March this year Nikkei Asia reported that at least a dozen institutions outside mainland China would have their access to China’s largest academic database cut. In a notice issued by the database operator of the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) the access limits were issued to ensure its ‘cross-border services are in compliance with the law’ Nikkei Asia reported.

The Challenges of Remaining Anonymous

The Chinese internet is strictly controlled, with the Cyberspace Administration of China placing heavy restrictions on the information that can be accessed and monitoring social media and website user activity. These restrictions are often referred to collectively as the ‘Great Firewall of China.’ Access to non-Chinese websites including Google, Facebook and YouTube are blocked. A list of some of the Chinese websites and apps that may be of interest to open source researchers can be found via Bellingcat’s Online Investigation Toolkit; they include search engine Baidu and social media apps WeChat (Weixin) and Weibo.

To access the mainland China versions of many of these platforms you are required to sign up with a Chinese phone number and SIM. The process of obtaining a Chinese SIM involves linking it to your real identity; this is one of the first challenges any open researcher will face. Until 2019, it was necessary to provide a photocopy of your ID when purchasing a SIM card, but later that year rules were updated to also require a facial scan as part of a policy intended to prevent fraud. As a result of these measures, remaining anonymous while doing open source research is extremely difficult. Researchers who are no longer based inside China but have obtained a Chinese-SIM while in the country may still face risks if they have family or friends inside the country. Reporters and dissidents living in exile have reportedly faced harassment abroad and their family members who remain in China have reportedly faced harassment and arrest.

Without the anonymity of burner accounts, researchers who login on Chinese websites and platforms expose their personal identity to the website or app provider who may then share that information with the government. These risks are obviously significantly higher for Chinese nationals. In addition to safety concerns, Chinese nationals often rely on social media accounts to access critical online services and this access could be put at risk if they use the accounts for open source research. For those based outside China, obtaining a Chinese SIM card is not straightforward and has been complicated since 2020 by travel restrictions due to Covid-19 which have only recently been relaxed.

Exploring Chinese Social Media

“The ‘platformisation’ of the Chinese internet has made things difficult because of the registration requirement.” Jessica Batke, a senior editor at ChinaFile explains.

“So much has moved onto WeChat.”

Social media apps Weixin (the Chinese version of WeChat)/WeChat, Weibo (a microblogging site similar to Twitter), Douyin (the Chinese equivalent of TikTok), Bilibili (a video sharing site similar to YouTube) and Xiaohongshu (an image and video sharing app similar to Instagram) are controlled in a similar way to websites, with a few important differences. For some of these platforms it is possible to sign up with a non-Chinese phone number – although you may only be able to access the international version of the app. On WeChat that means that the Moments (posts) in your feed will be subjected to a different degree of censorship than for the mainland China version. Mona Wang, is a PhD candidate at The Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton University and is currently working with The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab to investigate WeChat’s security and privacy practices.

“Something that is censored on the mainland Chinese WeChat account will not be censored on an international WeChat account,” Wang explains. At the same time, “images that are sent on international WeChat are being used to train, to construct the database of censored images on the domestic WeChat.”

The Citizen Lab team was previously able to create mainland China WeChat accounts by buying dual SIM cards purchased in Hong Kong that had two different phone numbers attached, a Hong Kong phone number (which begins +852) and a mainland China phone number (which begins +86). However it appears this is no longer possible as you are now required to provide your personal details to the mainland China carrier in order to use the +86 number.

Another challenge to conducting open source research using WeChat – either the mainland China or international version – is that in some cases you may be asked to have your account verified by another WeChat user. This could mean implicating other WeChat users in your research and exposing their account to increased scrutiny, while linking research accounts together by having them verify each other also leads to risks.

“It’s likely that if one of your accounts get[s] banned, they all get banned…All of this has made it really hard to obtain accounts for research.”

Security and spyware are also a concern with Chinese social media apps. Several of the researchers that Bellingcat spoke to were reluctant to have those apps on their personal phones. For researcher and investigative journalist Vicky Xu who works at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute; “[WeChat is] too surveilled…I only have WeChat on a China phone that I don’t use on my home network at all.” While the content posted on WeChat is known to be monitored, more technical research needs to be done to measure whether WeChat also surveils phone data and the precise nature of this threat (if any) still needs to be better understood. In the meantime, for at-risk populations who need to use WeChat, including journalists and researchers, taking a cautious approach to the apps you install on your personal phone seems wise.

While using a separate device for research offers some protection, it comes at a financial cost and the inconvenience means it may not be a practical option for independent open source researchers.

Human Sources

Contact with human sources has also been affected by tightening of internet restrictions. As Maya Wang, associate director in the Asia division at Human Rights Watch outlines:

“The communication we have with people on the ground is increasingly limited, especially in areas like Xinjiang and Tibet where the authorities now detain and imprison people for any connections abroad. So that makes it very difficult.”

It’s often crucial to verify online and open source material using other sources – corroborating material, documents or eyewitnesses. People who have been to a place or witnessed an event firsthand can be really important sources that confirm open source research. As Wang describes it: “The challenge is verification – then you have to go and verify with an actual human being and then the actual human beings are in China and how are you going to contact them?”

Diaspora communities – including minority Tibetan and Uyghur communities – continue to use Chinese social media apps to connect with people inside China: this has been an important conduit for information including about human rights issues. Sharing messages about sensitive topics on Chinese social media apps such as WeChat – which are not end-to-end encrypted and known to censor and monitor content in public and private chats in cooperation with the government – carries inherent risks. New platform rules on WeChat that were introduced by the Cyberspace Administration in 2017 have made administrators of groups liable for the content shared, meaning they are under pressure to delete posts that previously might have escaped censorship. Lobsang Gyatso Sither, Director of Technology at the Tibet Action Institute explains that reports of arrests- which people in the Tibetan community blamed on messages shared on WeChat- have had a silencing effect, with people being less willing to share information on the platform.

According to Lobsang, pressure has increased on the family and friends of activists who are still inside regions such as Tibet, in order to reduce exiles’ activism and cut down information sharing networks. This has been well documented within the Uyghur community. Lobsang explains,

“[It] leads to a lot of self censorship inside and also in the outside space because they don’t want to report…There are cases of Tibetans who used to be getting a lot of information, but they’ve stopped sharing that.”

This means that it isn’t only hard for those outside of China to look in; in certain places at least, it is hard for those inside the country to get messages out.

“The people outside Tibet have increasingly less information, even among the diaspora, and that’s by design,” says Maya Wang.

Non-Chinese Resources

Non-Chinese social media apps such as Twitter and YouTube are still important conduits for information to travel beyond the Great Firewall. In November 2022, videos of the White Paper Protests were sent to well known Twitter user Teacher Li, whose posts about the protests were widely reshared on Twitter. The use of platforms like Twitter are sanctioned in China but some users inside the country use VPNs to circumvent restrictions and upload material. The list of non-Chinese websites and social media apps blocked in China is long and includes multiple search engines, news sites and apps -including encrypted apps such as WhatsApp and Signal. A number of tools exist to check if a website is blocked inside China, however the results are a guidance only. Satellite imagery is a useful resource for open source researchers investigating China. This is especially the case for the imagery that comes from US and European providers, which is beyond the control of the Chinese government.

Balancing Transparency with Retaining Access

Just as resources and websites related to Xinjiang were removed from Chinese websites and social media after journalists and researchers published on the subject, the investigative techniques used to find this information are also subject to threat. Researchers explained to Bellingcat that it is difficult to speak openly about methodologies because as soon as they are made public they risk becoming unusable – due to new access restrictions for websites or barriers created to prevent the workarounds. This means that researchers are reluctant to share their techniques publicly because they fear losing access to them. This comes at the cost of transparency – a central tenet of open source investigation – as well as a lack of resources and open knowledge sharing for people new to the field to learn how to do this work.

Jessica Batke described the problem:

“Being too transparent about how you’re getting information, jeopardises continued access to that information.”

It also creates a problem for growth of the field:

“It hinders young people from being able to get into the field and do the best work they can because they can’t access the knowledge that some of us have built up.”

This lack of transparency also hinders knowledge sharing within the field, preventing re-use of methodologies for further research and getting in the way of the creation of new resources and techniques.

“There is no good answer to this problem,” Batke says.

Archiving Sites and Developing New Tools

The challenge with data collection of social media and web posts in China is that it lags behind events and researchers often do not have time to archive content before it disappears. Several researchers emphasised the importance of archiving, given the Chinese government’s aggressive censorship of websites and apps.

“There’s an imperative to archive things immediately when you find them, because a lot of things will not stay very long,” Darren Byler says.

The process of archiving Chinese websites and social media posts can also be onerous and there is a lot of work that could be usefully done to improve archiving tools.

As part of this research we tested a series of common tools, including western internet archiving sites and Bellingcat’s own Auto Archiver tool, to see how well they were able to capture Chinese websites or social media posts. Our tests produced mixed results. Sometimes webpages couldn’t be captured at all, or the archiving tool would only record the pop-up asking for users to register, even when the webpage was fully visible for several minutes before that pop-up appeared. With other tools, we were prompted to fill in a web CAPTCHA for each page we wished to archive. Automated tools could be inconsistent in which webpages they recorded, so we relied on manually inputting urls, then waiting to check that they had saved correctly, which ate up valuable time.

By conducting the tests, we found a particular need for tools that can record web pages automatically, without the need for the researcher to manually activate them (filling out CAPTCHAs for web based tools was particularly time consuming). Our tests also showed that there is likely value in developing tools that create an online inventory of archived information that is accessible to researchers, so they know what information exists, where it has been archived and where they can access it. This is particularly important since several researchers that we spoke to relied on screenshots and used screen recorders to document the websites they accessed in their work. Though they then publish those materials on their websites and on social media sites such as YouTube and reference them in their work, they are harder to find than they would be if there was a dedicated archiving tool. Some of the material recorded by researchers is only stored locally, on their laptop, or an organisation’s server, where it is both hidden from and inaccessible to other researchers. The lack of a public inventory and shortfalls in existing archiving tools means that knowledge remains fragmented.

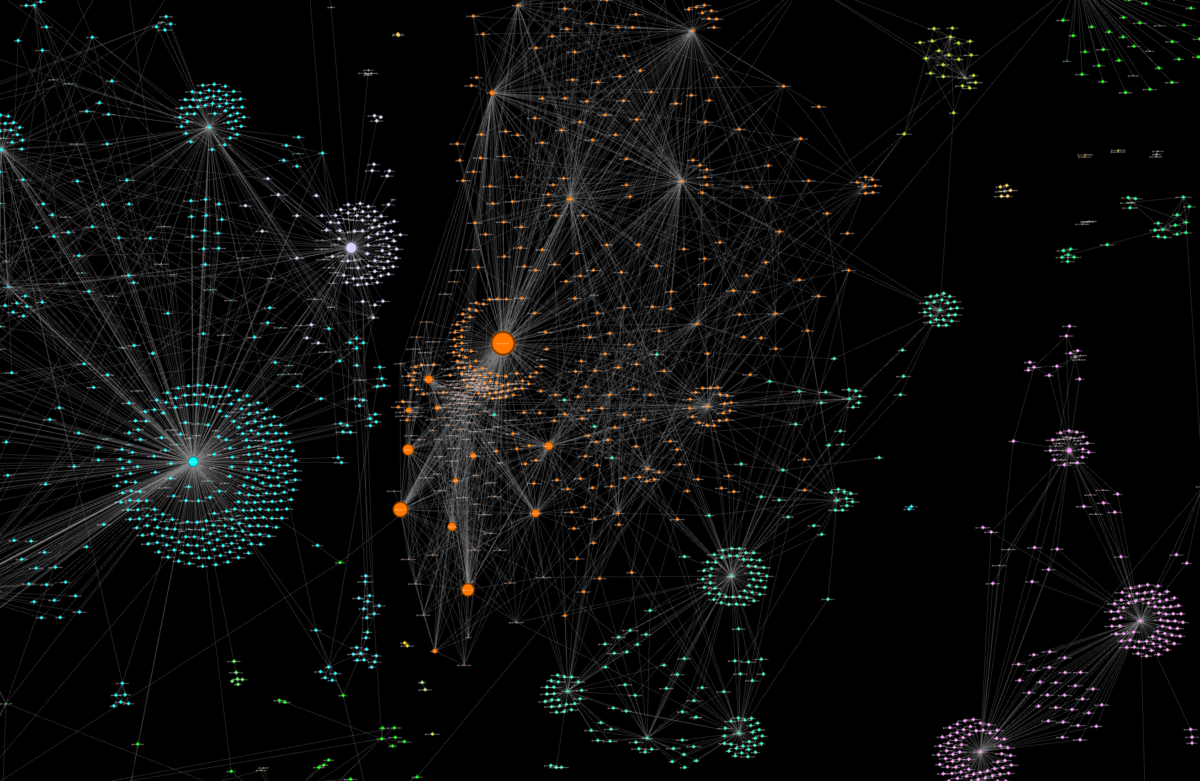

Some organisations are still finding creative ways to understand more precisely how censorship works on Chinese websites and apps and tackle the problem of archiving at least some censored content. Great Fire have built a series of websites to document censorship on WeChat, Weibo and Zhihu, by collecting posts by specific users as well as posts with certain hashtags and comparing what remains from one day to the next. The posts are available on Great Fire’s websites and are colour-coded to indicate whether they were censored or not. The fact that only a fraction of the daily posts are archived and that the addition of new archiving terms can only be added once their importance has become obvious means that the Great Fire website can only show a fraction of the posts that have been censored.

“Those systems of control and censorship are becoming more complex and more immediate, there’s automation… that’s a shift as well in the past five years, with things being taken down more quickly.” Darren Byler explains.

For the Great Fire team that means new terms can only be added to the daily collection once their significance becomes clear; by which time they may already have been censored.

The Future of Open Source Research and China

There remain many questions about how to access and archive Chinese apps and websites given current registration requirements and evolving censorship. Journalists and researchers continue to do valuable work to investigate China, relying on leaked documents, or combining open sources such as social media posts and satellite imagery with on-the-ground reporting. A number of researchers including The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab are investigating Chinese social media apps such as WeChat to better understand how they work and how censorship functions within them. There is ample opportunity for researchers and developers in the open source community to tackle the challenges outlined above – to build new archiving tools and to find creative ways around the censorship and registration requirements that are hampering current investigations.

This article was produced as part of Bellingcat’s Tech Fellowship program, which seeks to create investigative tools and online resources for open source researchers.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here.