How (Not) To Interpret Far-Right Symbols

There’s a good chance you’ve seen a photo like this before: a man with a shaved head and a black jacket faces away from the camera. He’s got a swastika tattooed on the back of his head as a Nazi flag flutters in the background.

It’s the kind of default image we often have of when we think of the far-right — obvious, identifiable and recognisable. That’s why this exact photo has been the cover image for so many articles about the far-right around the world. No matter that the image itself is from a very specific context, when a handful of neo-Nazis protested outside a Holocaust memorial centre in Illinois, USA back in 2009.

But it’s seldom this straightforward to identify symbols the far-right uses, let alone identify members of far-right groups or advocates of such ideologies solely because of the symbols they use.

For every culture, symbols of any kind matter. They evoke emotions in us, from the positive to the negative and the simple to the complex.

Of course, this certainly doesn’t just exist in the context of far-right extremism. Think of the kinds of symbols in your life that you react to and the national, cultural, or subcultural contexts you come from.

Maybe it’s a symbol you’re quite literally attached to, tattooed on your body. Maybe it’s a symbol that angers you to the point where you feel your identity is threatened. Maybe it’s somewhere in between. You feel a bond, some sense of community with those who view and react to these symbols in the same way.

So symbols mean different things to different people, at different times and in different contexts. They’re not static, nor are they usually as simple to interpret as the swastika tattooed on the back of that neo-Nazi’s head. They have multiple levels of meaning, even contradictory ones. This is particularly the case for the far-right, who use symbols in deliberately coy and confusing ways that make it more difficult to pin down who they are and what they believe in.

In her 2020 book, the US sociologist and expert on the far right Cynthia Miller-Idriss called this technique “game-playing” — coded messages laced with ambiguity, irony and humour with which the far-right not only “troll” their perceived opponents, but help “carry extremist ideas into the mainstream.”

Symbol, Context, Intention: Keys to Interpreting a Far-Right Symbol

So how should you go about interpreting, understanding and analysing a symbol which you think is or could be affiliated with the far-right?

There are three questions you should ask yourself, in any order you please. As you’ll see, these are questions that some of the simplest digital investigative tools and techniques — web searches and image searches — can help answer.

What symbol(s)?

Sometimes this question is relatively simple to answer. The far-right often uses obscure symbols or co-opted national symbols, such as the Patriote Flag in Quebec. They use symbols that have multiple meanings and symbols also used by non-extreme mainstream actors, such as the Eureka Flag in Australia. They even use symbols that are only meant to hint at the existence of other, more extreme symbols.

It should be noted that while ultranationalist movements flourish across the world, such as in India, Israel, Japan and Turkey, the symbolism detailed in this article comes from white nationalist and far-right extremist contexts in Europe, the Americas and Oceania.

Many of these symbols can be found on regularly updated databases maintained by organisations such as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

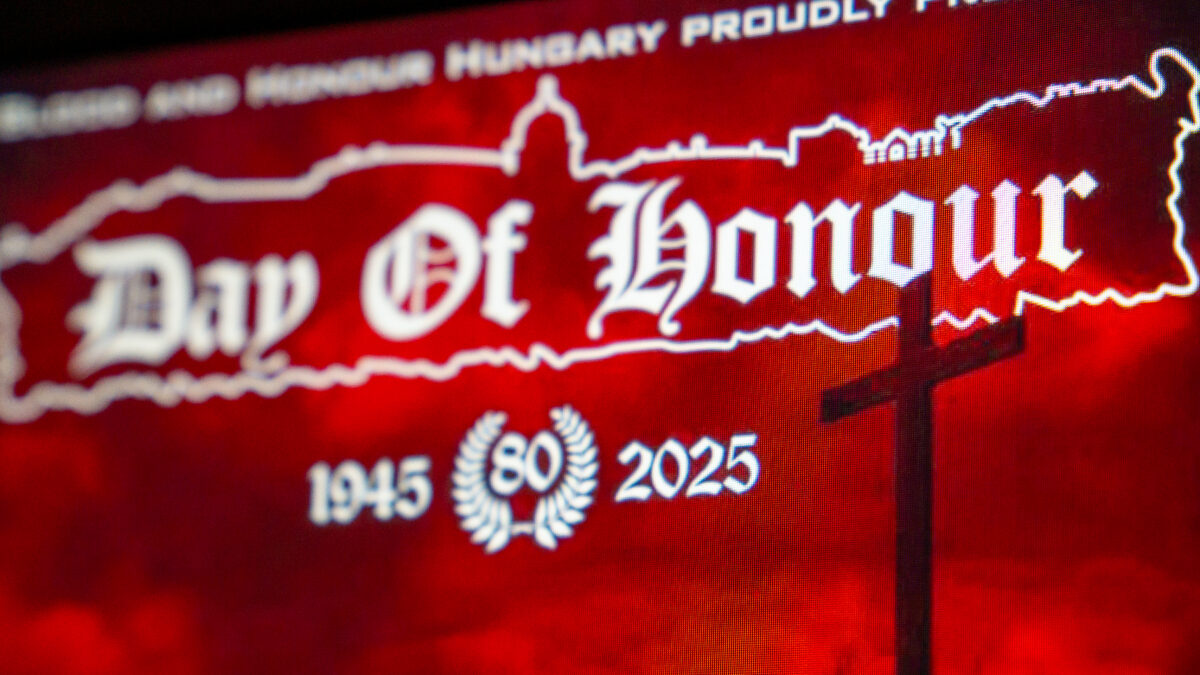

This t-shirt is sold on a website from a small European country.

The text reads “me ne frego” — an Italian phrase roughly translating as “I don’t care”. A quick search online will reveal that it was used as a motto by Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party.

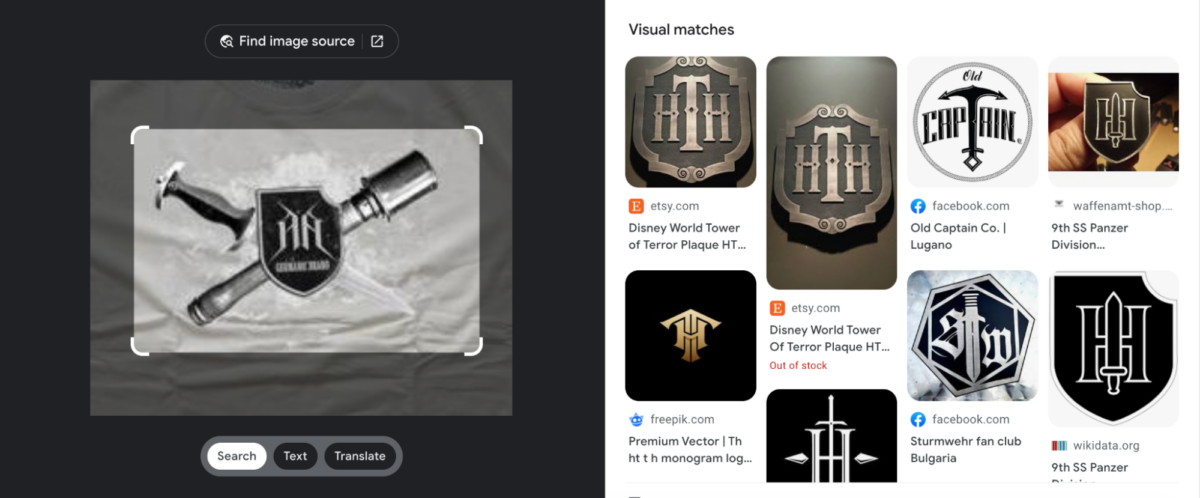

Here’s another example, a smaller screenshot of a t-shirt sold by another European far-right website.

A lot of clothing in the world bears military-style design. That alone is not evidence of far-right ideology. But note the distinctive shape of the shield. This specific shape, with a notch on the upper right-hand corner, was used by Nazi Germany’s Waffen SS Panzer divisions (other divisions’ patches had notches on the left-hand side, while some had none at all).

In addition, the brand’s logo could be interpreted as reading “HH” — a common far-right shorthand for “Heil Hitler.” For example, according to a report on extremist dress codes by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, a German foundation, the Norwegian fashion brand Helly Hansen has been worn by far-right extremists who import the same meaning to its acronym ‘HH’.

Lastly, here’s another example of a t-shirt sold by a European far-right website.

There are several symbols we can analyse here — text reading “the colours of tradition” followed by the brand’s name. Those smaller coloured symbols resemble a Celtic cross, a symbol commonly used by the far-right. Here they also contain the brand’s initials.

The words “colours of tradition” suggest that the use of black, white and red is significant. These are the colours not only of the old Imperial German flag but also of the flag of Nazi Germany — colours that were important enough to Adolf Hitler himself to note in Mein Kampf why the Nazis should use them.

Neo-Nazis in Germany, Austria and beyond have long used these colours as allusions to these flags in order to circumvent prohibitions on swastikas and other more overt Nazi imagery.

Who, When, Where? Understanding Context

It’s a cliche to say something like ‘context is everything,’ but it really is true when you’re trying to understand far-right symbolism.

The contextual spoiler for my three image examples above: they are from known far-right fashion brands. A quick reverse image search of all three photos will land you on the pages of these brands. (To that end, use a browser extension, like Search By Image or RevEye, to allow you to easily and quickly look for images across different search engines).

On the websites of these brands, you’ll see example after example of far-right symbolism, some more extreme and some more subtle. Researching their names reveals that these brands are well-known across European far-right extremist scenes.

Every symbol you see, far-right or not, exists in a context. Always ask yourself:

Where is the symbol you’re seeing? Is it on a social media page or account? If so, what other symbols does that page or account share? Are you seeing a symbol in a physical place, like a sticker or a piece of graffiti? If so, what other symbols are around it?

Who has communicated the symbol? Is it a specific group or individual? What else can you discover about them and their associations?

If it’s a piece of media, when was it photographed or filmed? Was it around the same time the image was posted? To what extent can you chronolocate the image — that is, narrow the time down to a year, season, day or even time of day if necessary?

These questions can often be answered using elementary online open source verification techniques.

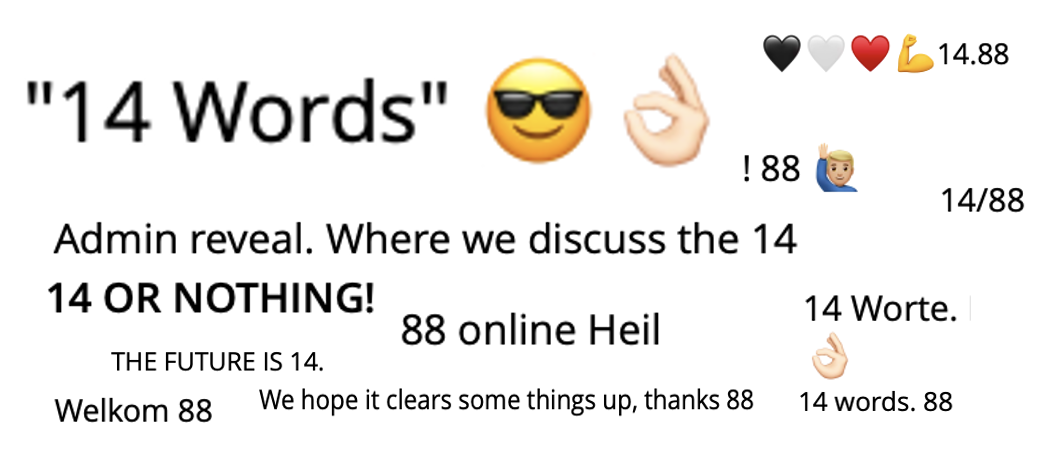

Context is key. For example, far-right extremists, especially on social media, like to use common number codes as symbols. Among others, there’s 14, referencing the neo-Nazi ‘Fourteen Words,’ or 88 (‘Heil Hitler’, ‘H’ being the 8th letter of the alphabet), and more.

But if you were to see someone with, for example, an Instagram username with a ‘14’ or ‘88’ and proclaim that on this basis alone the user is a far-right extremist, you could be making a serious mistake.

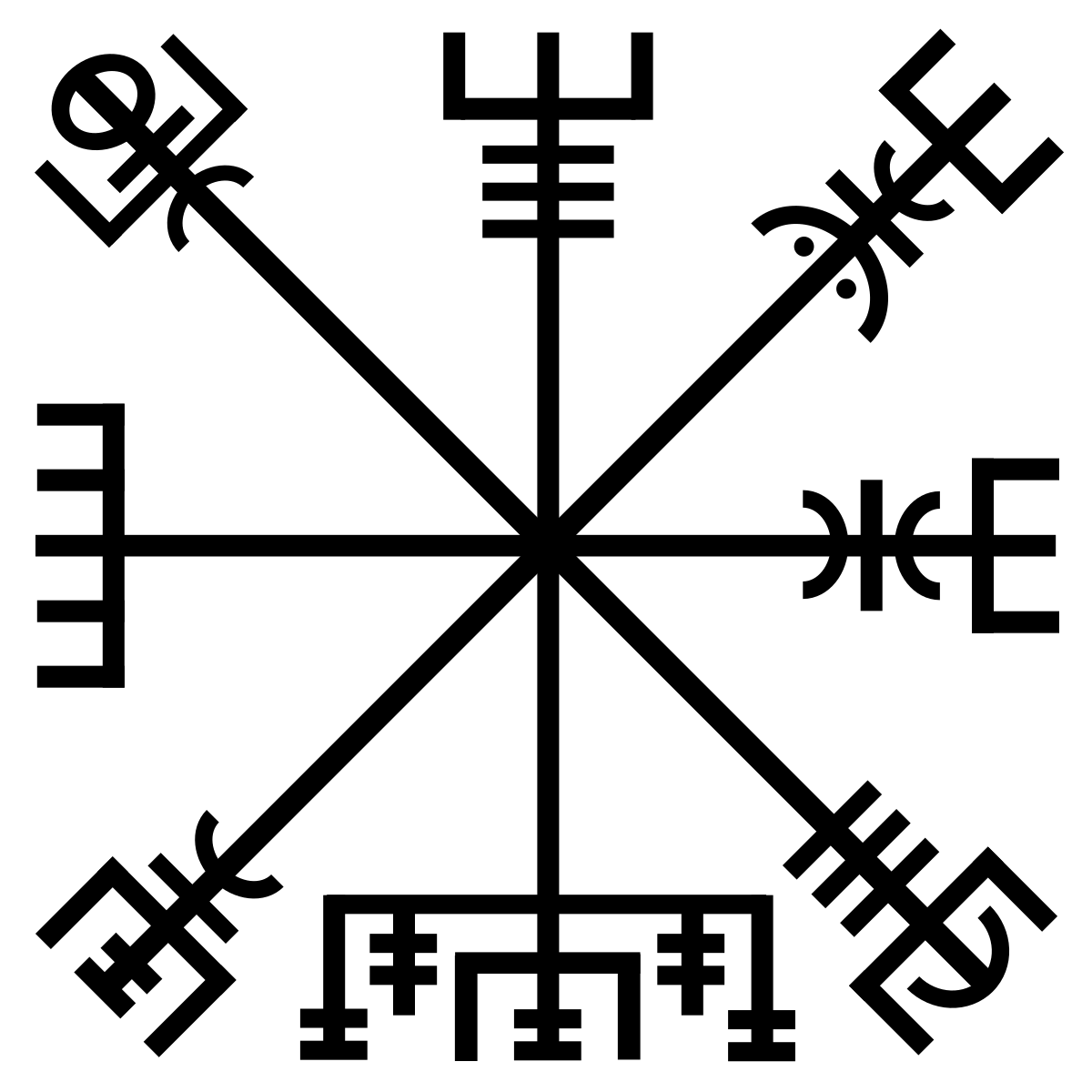

The same goes for imagery co-opted and frequently used by the far right, like neo-pagan or Norse symbolism. For example, maybe you see someone in a photo with a visible tattoo like a vegvísir (a ‘wayfinder’ or compass symbol that resembles a snowflake) wearing some sort of clothing or jewellery with a mjölnir (Thor’s hammer).

There’s no shortage of people affiliated with far-right extremist groups who adopt and wear these kinds of symbols. But there are plenty of people who have nothing to do with the far right who wear and display these kinds of symbols as well.

Bikers, religious groups and heavy metal fans with no far-right sympathies have all used this symbolism. These symbols are often a necessary clue of far-right affiliations, but without further context they are seldom a sufficient one.

Why? Establishing Intent

Assessing intention can be the most challenging. It’s crucial to understand why a specific far-right symbol has been communicated at a specific time and place (virtual or physical) by a specific actor. This also means there’s a chance that someone displaying a far-right symbol — or what you think is a far-right symbol — isn’t doing so deliberately or doesn’t even know that people might interpret a particular symbol that way.

First ask: who are the target audience(s)? Members of the general public? Existing members of the group or adherents of the ideology? Potential new recruits? Perceived adversaries or enemies (e.g., journalists)? Not every symbol flashed by a far-right group is intended to be seen by the same audience or interpreted the same way by different audiences.

Interpreting and analysing the far-right’s use of symbols can be a challenge because of a seeming lack of consistent messaging. Austrian linguist Ruth Wodak, who has written extensively about communication strategies used by the far-right, uses the term “calculated ambivalence,” which she describes as “the strategy of addressing multiple and contradictory audiences via a single, cleverly layered message.”

As Bellingcat wrote in 2020, even Hawaiian shirts have become an example of this calculated ambivalence in action. They’ve been worn by some US extremists to flaunt their readiness for a forthcoming civil war, building off a number of subcultural references and memes. An even more innocuous example is the US and international far-right’s use of the ‘OK sign’ hand gesture.

In 2017, far-right extremists on the website 4chan started a hoax claiming that the ‘OK’ hand gesture, an everyday gesture in the US and English-speaking world, was actually a hate symbol. They did so in order to provoke an overreaction from the media and opponents of the far right.

Far-right extremists began using the symbol, posting photos of themselves making the gesture in order to troll and “trigger” their perceived opponents. The hope was to make them look ridiculous and mockable for claiming something so common was a far-right extremist symbol.

The far right’s use of the hand gesture has certainly remained an act of trolling — as antiextremism watchdog the Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC) writes, it’s a symbol which is “so widely used that virtually anyone has plausible deniability built into their use of it in the first place”. But it was deadly serious when the Christchurch terrorist, after his arrest in 2019 for murdering 51 people at two mosques in New Zealand, flashed the symbol in court before the cameras.

To paraphrase Wodak, there’s a double message at play here: one can either view a far-right extremist’s use of the ‘OK’ hand gesture as just a coincidence — i.e., a mainstream, non-extreme use of the gesture — or they can share the far-right extremist meanings implied by those making the gesture.

The far right, whatever kind of symbol they’re flaunting, is interested in playing games like this.

They’re more than happy to exploit the ambiguous, multivocal and often contradictory nature of symbols, especially in this digital age where we’re all bombarded by them every day. There are certainly some who are still as brazen as that neo-Nazi with the swastika tattoo, but today’s far-right extremists are far less conspicuous and much more creative in the ways they communicate the same old hateful views.

Cover image showing crossed-out far-right graffiti in Sofia, Bulgaria (c) by Michael Colborne, 2022

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here.