Samos And The Anatomy Of A Maritime Push-Back

Samos And The Anatomy Of A Maritime Push-Back

Refugees and migrants have all but stopped arriving on Greek islands amid mounting reports of maritime push-backs. In April of 2020, the UN Refugee Agency recorded a single landing with 39 people. During the same period in 2019, there were 1,856 arrivals by sea. The near-complete drop off follows a border standoff between Greece and its neighbour, Turkey, which shifted its stance in late February, saying that it would no longer prevent the estimated four million refugees and migrants it hosts from crossing into the European Union.

Greece has denounced what it calls “extortion diplomacy” by Turkey and suspended access to asylum during March. But while the asylum system has officially reopened since April 1, arrivals have not resumed — certainly not to the levels from the past. The Greek government, conscious that push-backs break international law, has briefed national media that it is pursuing a new dogma of “aggressive surveillance” without specifying what this strategy entails.

First of all, we must establish what push-backs are.

According to the European Convention of Human Rights:

“Push-backs are a set of state measures by which refugees and migrants are forced back over a border – generally immediately after they crossed it – without consideration of their individual circumstances and without any possibility to apply for asylum or to put forward arguments against the measures taken. Push-backs violate – among other laws – the prohibition of collective expulsions stipulated in the European Convention on Human Rights.”

Greece, as well as other EU frontier states such as Croatia, has long been dogged by accusations of push-backs. Respected human rights groups have collected dossiers of witness testimony which typically allege that phones have been confiscated during such operations. However, in the absence of corroborating evidence that these devices might provide, these accusations have largely been ignored.

Maritime push-backs, taking place far from any of the cameras onshore, present an even greater evidential challenge. However, as part of a broader investigation into push-backs conducted jointly with Deutsche Welle, Trouw, and Lighthouse Reports, we have collected evidence to demonstrate how one of these operations worked in practice. The result is the most precisely documented push-back of its kind.

We verified three videos and gathered the accounts of two witnesses who were themselves pushed back, as well as the account of a relative of one of the victims. We confirmed that the people we see across three separate videos, including footage of these refugees on the Greek island of Samos, are the same. We cross-referenced this with local radio broadcasts reporting their arrival and social media posts by islanders who saw them.

April 29, 2020 – Aydın, Turkey

On April 29, the Turkish coast guard (TCG) shared a video and pictures of a rescue operation they claimed happened that day. According to the TCG website they had recovered a total of 22 people who were adrift off the coast of Aydın province near the Dip Burnu peninsula.

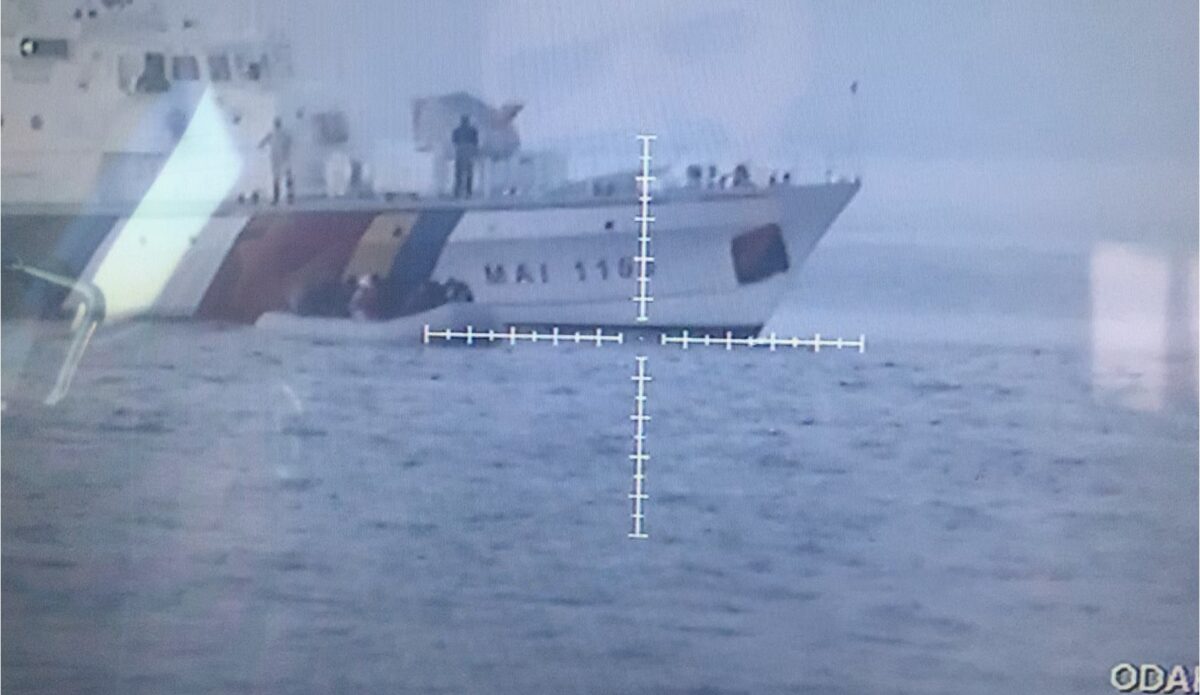

The video contains three main sections: in one of the scenes we see the inside of the TCG vessel. The captain films the dashboard where we see what time it is (10:16:11 AM UTC, 13:16:11 Greek time) and the coordinates (37.621833, 26.952611). He then shows two Greek vessels and a life raft that is being towed by one of them.

Then it cuts to footage from a different camera closer to the Greek vessels. The Greek ships are the LS146 and the SAR boat 513 from the Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG).

After another cut we see one more ship, this is the LS050 also from the HCG. The orange vessel, marked 513, appears to be pulling a black-orange life raft behind it.

In the remainder of the video we see how the TCG recovers people from the raft and checks their temperature while they are boarding. The faces of the people being rescued are clearly discernible and their clothes are also distinguishable.

The video itself is suggestive of a push-back, but how do we go from here to proving what actually happened? For that, we had to closely examine the events leading up to the video, beginning the day before.

A Well-Documented Arrival

April 28 was a significant day on Samos, one of the five eastern Aegean islands that has been used by the European Union since 2016 as a kind of buffer zone to contain newly-arrived asylum seekers.

It was the day of the visit by Greece’s Migration Minister Notis Mitarakis, the politician who has spoken publicly about taking a harder line on asylum and migration. The minister’s arrival coincided with reports on Samos itself of a new landing by refugees and migrants.

On Wednesday, April 29, at 02:17:35 UTC, a video was posted on Facebook showing migrants arriving on an island. The post came from the Consolidated Rescue Group, a Facebook page which regularly publishes video evidence showing apparent endangerment of refugees or migrants by both the Turkish and the Greek coast guard.

The person filming says the date is April 28. The footage consists of two videos that have been stitched together. The first video shows a group of people at sea on a dinghy heading for an island. The second video shows them on a steep hill next to a small cove. We were able to identify the island, to approximate the position of the dinghy, and to geolocate the hill-side vantage.

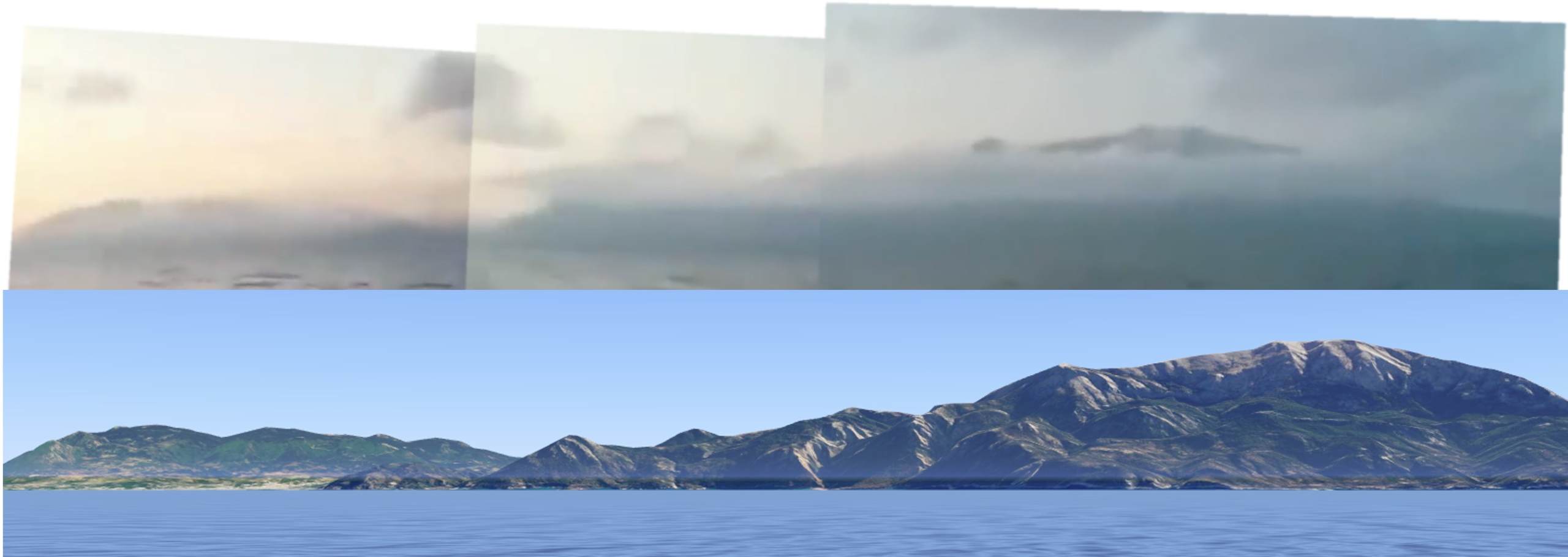

The first segment was shot at sea, just north of Samos on its westernmost side. We know this because of the mountain range in the background.

When compared to the 3D model from Google Earth it was consistent with the horizon of Samos.

Top: panoramic still from video. Bottom: the island of Samos from the north-west

In the other video segment, we see a cove when the person filming turns their phone toward the sea. Given what we know about their approximate position approaching Samos, there are only two coves that could match the one seen in the video.

Panorama of video taken by asylum seekers

Under the Facebook video, some users left comments saying that they had relatives and friends who were aboard the boat and asking if anyone knew what happened to them. We contacted these people. One individual shared a WhatsApp location sent by a member of the group on arrival. It was shared 07:51 Greek time and the location corresponds with that of the western cove.

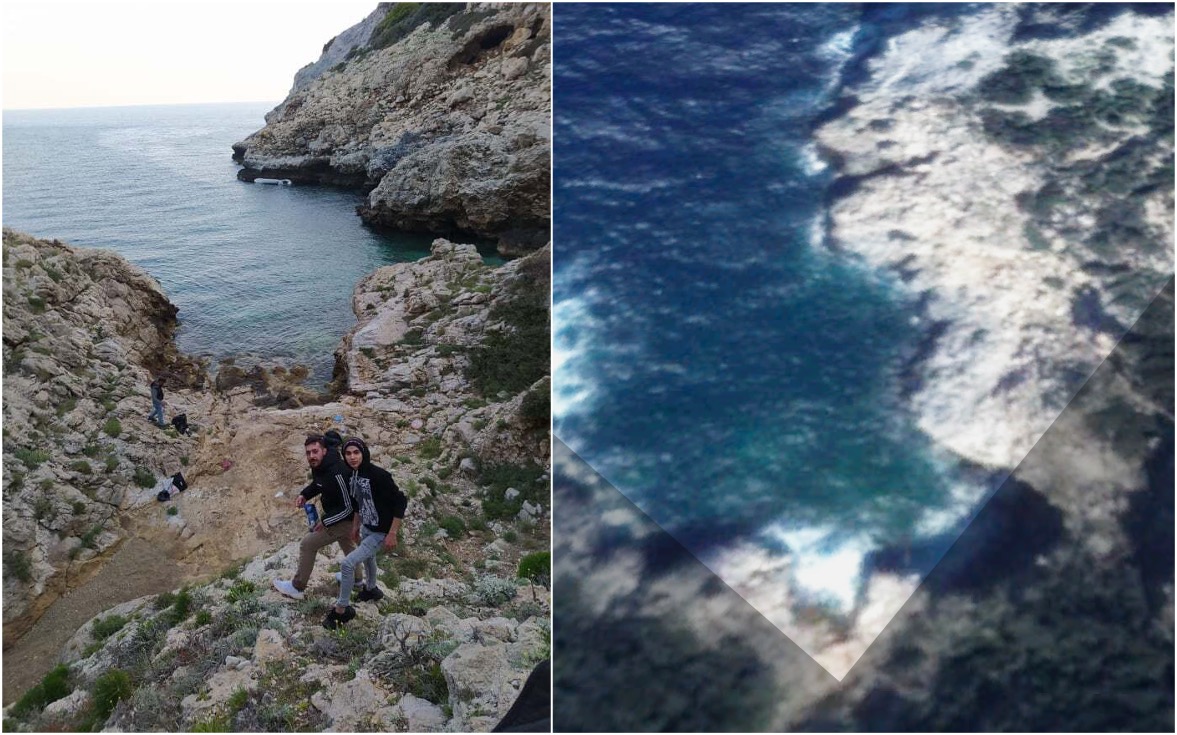

We were sent an additional image by one of the asylum seekers who were part of this group, which confirmed they landed at the western cove, at 37.763515, 26.602741.

Left: image sent to us by a member of the group who landed on Samos. Right: Satellite imagery (courtesy of Google Earth/Maxar Technologies)

The next step was to establish what time the group arrived on Samos. We know it was in the morning, because of the time that the WhatsApp location was shared. During individual interviews with migrants who were part of this group, all put the time of arrival at around 7:30 that morning.

We do not need to rely solely on their testimony. In the video, we see the sun is about to rise from the northeast when the group is still on the dinghy, near Samos. The time of sunrise on Samos that day was 06:18. This time is consistent with the people reaching Samos itself at about 07:30 local time.

First light is clearly visible as the asylum seekers approach Samos

The cove we see in the video is located at a distance of only about 800 meters from the village of Drakei, but the climb from the cove to the village is extremely steep and may have taken considerably longer than the distance would suggest.

Mentions Of Migrants On Radio And Social Media: 28th of April, 2020

The first recorded mention of the new arrivals comes on local radio 2000 FM, when a local woman from the village of Drakei, who owns a shop next to a church, told the host, Giannis Negris, that she saw roughly 17 people passing through the village. At noon, the host received a call from a man who told him that two police vehicles were on their way to Drakei. Negris decided to call the hospital to see if the migrants were checked there, but the hospital told him that no migrants had been admitted that day.

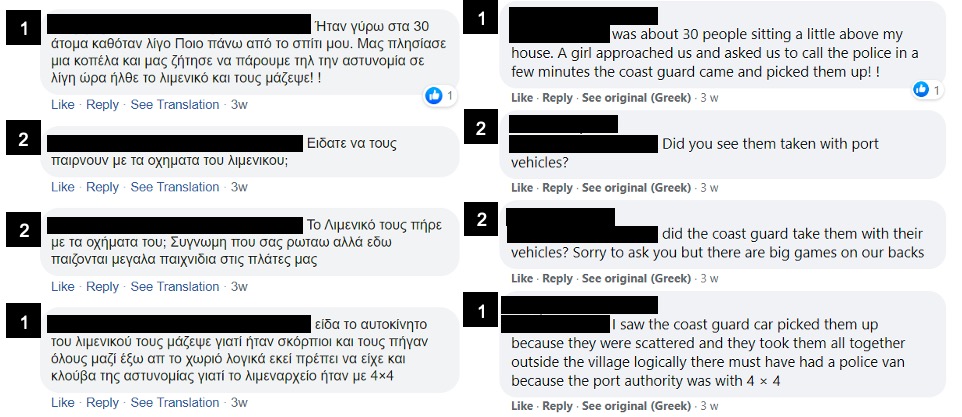

Posts made by locals on social media also discussed the issue. In the post below an eyewitness claims they saw this group being apprehended by the authorities when they arrived at the village.

Posts made on Facebook by locals. Left: Original Greek, Right: English translation

The social media post of the incident claims the group was picked up by the port police. According to one of the asylum seekers from this group, who later spoke to us, they were taken to the shore and loaded onto a vessel they remember as being orange. They were taken to and put aboard a second vessel, before eventually being forced onto an orange-black life-raft whose description matches the one we see in the Turkish footage of April 29.

At 7:30 PM, a couple told Giannis Negris they were driving near Mikalis when police stopped them and demanded to see their “codes” (permission to go out during the Covid-19 lockdown in force on the island during this period). The police then asked them to leave the area due to an unspecified exercise by security forces. The couple left the location, but not before one of them was able to spot a Hellenic coast guard vessel pulling a life-raft.

One of the asylum seekers stated that their group were towed out to sea on the same day they landed and left adrift in Turkish territorial waters. People aboard the life-raft could see Turkish coast guard vessels nearby but these boats did not intervene. The asylum seekers said that the tide kept pushing them back into Greek territorial waters. Each time this happened the Greek vessel would use its wake to push the life-raft back into Turkish waters. This push and pull continued overnight and into the afternoon of the next day (April 29), when the Turkish coast guard finally picked them up. Confirmation of this last part is seen in the video published by the TCG.

In addition to the video material, we found corroborating evidence from multiple sources giving near identical accounts of incidents, locations and times. In all cases, they state that on that day, a group of migrants arrived near Drakei and that they were detained shortly after.

Matching People

After confirming the location and time, we were then able to match the individuals from the three separate videos and establish that they are indeed the same people in each. This demonstrates that we see the same people arriving on Samos, before later being picked up by the TCG. In all cases below the footage taken by the asylum seekers is on the left, while the footage taken by the TCG is on the right.

A Pattern Of Push-Backs

Our reconstruction of April 28 and 29 is built on a mixture of open source evidence, which includes videos and pictures, as well as testimony from the group of asylum seekers and locals on Samos. We have located this visual evidence in time and space and found that it corroborates the accompanying witness accounts we were able to collect.

What is potentially unique here, in relation to reported push-backs, is the chain of evidence. In other instances, there is either no footage of migrants being pulled back into Turkish territorial waters by the Greeks, or there is no open source evidence that confirms absolutely that asylum seekers actually made it onto a Greek island.

A good example of these partially evidenced cases came on April 30 on Chios, another Greek island in eastern Aegean, where migrants allegedly arrived on the island before being pushed back. In this case the migrants ended up on an uninhabited islet called Boğaz Adasi inside Turkish territory, where they were later picked up by the TCG. There is footage of the people being taken off that islet and there is footage of a dinghy presumed to have been used by the same group on the shore of Chios.

TCG rescuing migrants from the Boğaz islet near Çeşme, Turkey

As was the case on Samos, local witnesses discussed seeing the group on social media. This was also picked up by local news sites, that claimed there were newly arrived migrants on Chios, although some of these posts were later removed. So far, however, no images have emerged that show the same individuals on land on Chios.

Dinghy used by migrants who allegedly arrived in Chios on April 30, 2020.

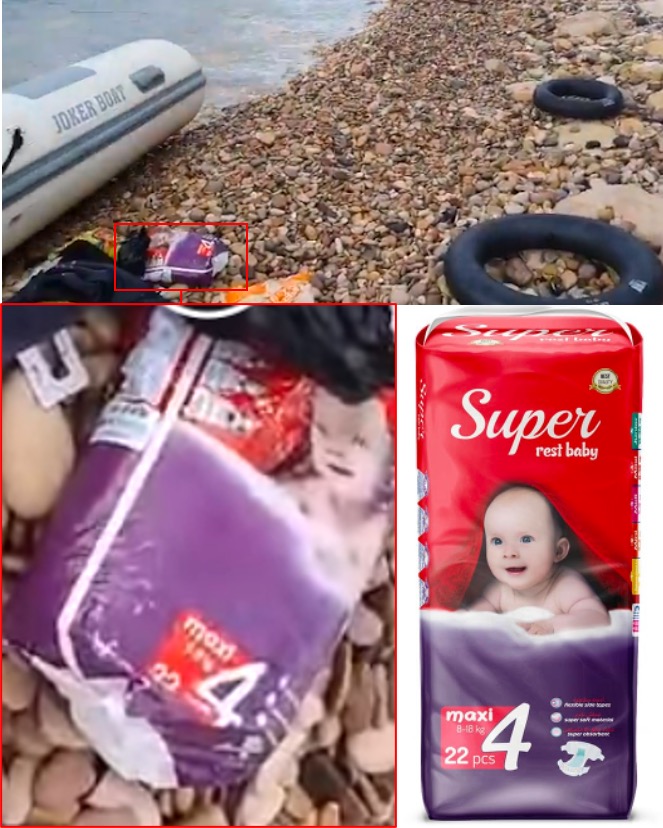

A pack of diapers that was presumably left behind by migrants. This brand of diapers, Super Rest Baby, is sold in Turkey

The Chios example is important because the depth of local testimony would normally be taken as proof of the incident in the absence of photographic evidence. A common complaint among victims of push-backs is that their phones are confiscated when they are taken into custody and prior to being coerced back across the border. In the Samos case, the visual evidence chain remained unbroken, because the video and locations were shared prior to the group being detained.

In the Samos case we were able to establish contact with two asylum seekers who were part of the group pushed back, as well as the husband of one of the women in the videos. They all confirmed the group made it onto the island, and that the members were detained and almost immediately pushed back.

The people we spoke to were also frustrated with Turkish authorities who left them adrift through the night of April 28 and into the following afternoon before taking action. Relatives of the group were left uncertain of their fate because the individuals we see rescued on April 29 were later transferred to a detention center in Aydın, Turkey, where they were quarantined for 14 days without access to a phone before being released.

This was a joint investigation conducted by Youri Van Der Weide and Bashar Deeb