A Guide To Monitoring Conflict Amidst a Sea of Misinformation

Join Bellingcat’s WhatsApp Channel for the latest news and resources from us.

How does one monitor a conflict zone on the brink of civil war, especially in a region which is difficult to access, experiences frequent internet shutdowns and where misinformation is common? In this guide, we outline the open source tools and methods we can use to evidence what is really happening in many such conflict settings.

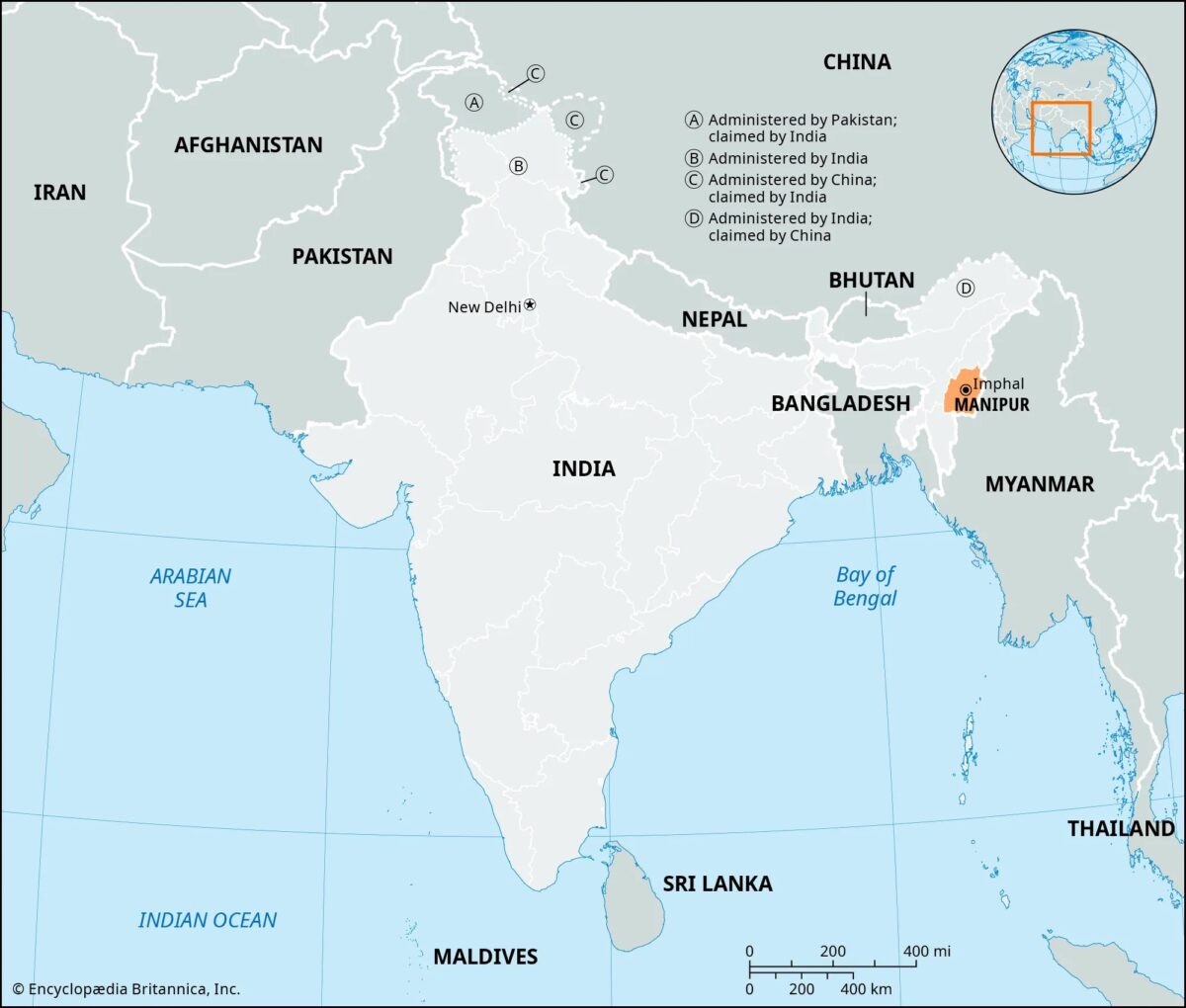

Our focus for this guide is on India, which recorded 84 internet shutdowns in 2024 – the highest number amongst democratic nations. In early June, authorities imposed a curfew and suspended internet access in parts of Manipur after protests erupted over the arrest of ethnic leaders. The state, in the north-east of the country, has been wracked by violence for years.

The ethnic conflict between the majority, mostly Hindu Meitei population and the indigenous, largely Christian Kuki Zo communities is one of the worst spates of violence Manipur, also known as the “Land of Jewels”, has experienced in decades.

The Imphal valley in Manipur is surrounded by mountains. It is home to 39 ethnic communities. Just over half of its nearly three million residents belong to the Meitei community, followed by the Naga (20 percent) and the Kuki Zo (16 percent) tribes.

The landscape is complex, with ethnic armed groups divided into multiple factions (this list is not complete):

- The ethno-nationalist militia – yet to be designated as a banned group – Arambai Tenggol (AT), the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) – Meitei

- Kuki National Army, Kuki National Front – Kuki

- Zomi Revolutionary Army – Zomi

- National Socialist Council of Nagalim (Isak Muivah) – Naga

In May 2023, the Manipur High Court passed an order recommending a Scheduled Tribe status (a category for indigenous communities in India that guarantees affirmative action and constitutional protection over identity and land) for the dominant Meitei community. Tribal communities rallied against the decision while the Meitei community held counter-rallies and counter-blockades. Clashes broke out between the Kuki and Meitei groups. Since then, the conflict has displaced more than 60,000 people and claimed more than 260 lives from both communities.

In this guide, we show you how to use open source methods in any secluded area to:

- Analyse weapon imagery and the groups using them

- Investigate weapons that were looted and where they ended up

- Analyse images of drones potentially used as weapons to deploy munitions

Analysing Weapon Imagery

One effective approach for open source researchers is to trace the digital footprint of weapons. In the Manipur case, local armed groups, such as the Arambai Tenggol, the UNLF and the Kuki National Front, have been posting weapon imagery mainly in WhatsApp groups and Facebook accounts.

Support Bellingcat

Your donations directly contribute to our ability to publish groundbreaking investigations and uncover wrongdoing around the world.

According to media reports, the war has been fueled by weaponry looted from police armouries or procured on the black market either from Myanmar, across the border, or through surrenders in amnesty drives.

The 6,000 firearms looted included pump-action shotguns, grenade launchers, AK-pattern rifles, INSAS rifles and ammunition. The police claimed that in February and March alone, more than 1,000 weapons were surrendered, with more than half from the Meitei-dominated valley districts, where a majority of the weapons were looted.

Bellingcat analysed weapon imagery from 2023 and 2024, accessed from WhatsApp groups and Facebook accounts linked to non-state actors, including the AT, Kuki Zo militant groups, and various volunteer organisations. While these groups have surrendered some weapons in amnesty drives, many sophisticated weapons were not turned in and were only recovered in search operations by security forces.

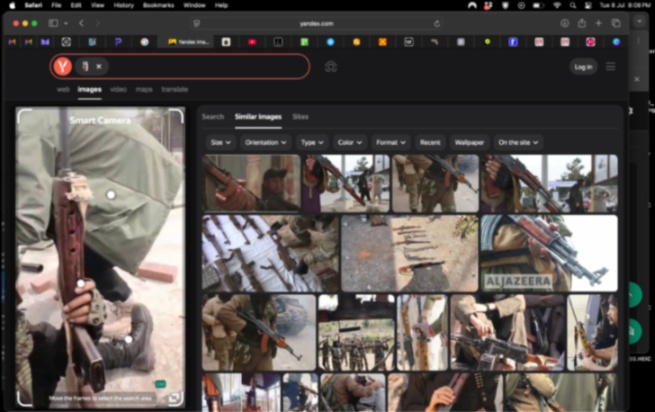

For verification, we ran screenshots of images of the weapons without visible serial numbers or other markings first through reverse image searches on Google and Yandex. Then, we cross-referenced the images with resources like the Small Arms Survey handbook and Open Source Munitions Portal (OSMP).

However, these databases are limited in their documentation from India.

We also looked at the public dashboard of Conflict Armament Research (iTrace). This is a far larger data source. However, the full dataset, which contains a huge number of images of weapons from around the world, is not publicly available. Only broad statistics, and no images, are visible via the dashboard.

The Small Arms Survey handbook helped match and identify, to an approximate accuracy, some of the older weapon models published on social media platforms and YouTube. However, the guerrilla modifications or customisation of weapons by the militant and militia groups made it challenging to identify the specific models.

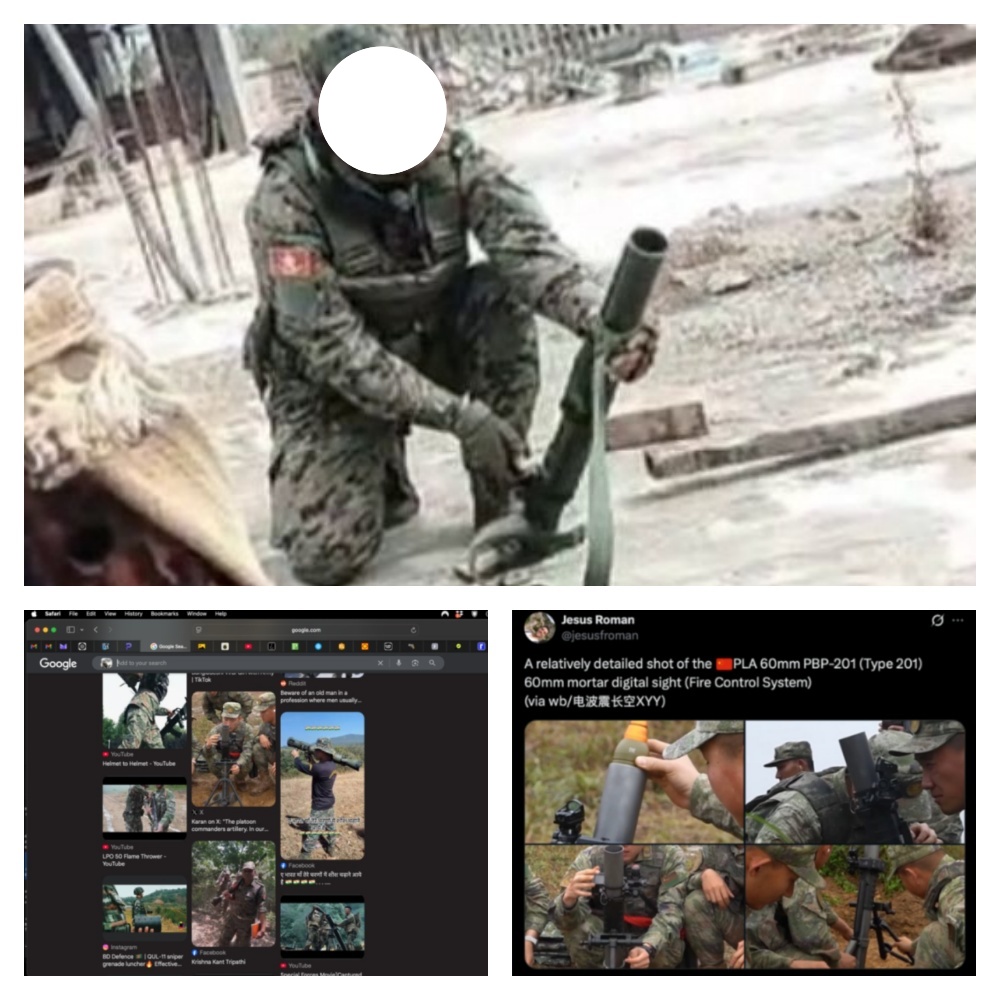

This was the case in a video posted on X, which purported to show militants preparing to fire a mortar projectile.

By breaking down the video into frames using InVID, a platform that contains a number of useful tools for analysing videos, we were able to identify the weapons, providing clearer imagery we could use to go back to reverse image tools on Google and Yandex, as well as the Small Arms Survey handbook.

We identified three weapons from the video:

- A bolt action rifle

- A FAL (Fusil automatique leger)

- A 60mm commando mortar

The shape of the weapon held by the militant wearing the beanie cap and scarf in the same video matches a FAL pattern rifle, such as the Indian 1A1 FAL, which has a distinctive long wooden handguard with multiple elongated ventilation holes.

“In India, the rifle was produced by the Ordnance Factory, Tiruchirappalli and was in service up to 1998, when it was replaced by the INSAS Rifle. Over a million units of the 7.62 mm SLR rifle have been produced by the OFB,” wrote (Retd) Major General Dhruv C Katoch, who previously served as the Director for Centre for Land Warfare Studies.

Also visible in the video is an unidentified model 60mm commando mortar. Commando mortars are characterised by a more portable design, typically featuring a much smaller baseplate and a sling or carrying handle rather than a bipod, all of which can be seen in the images below. The reverse image search on Google led us to a file photo on Wikimedia posted by the US Army, besides this assessment by Jesus Roman, Editor of Revista Ejercitos.

Munitions researcher and PhD candidate in War Studies at Kings College London, Andro Mathewson, described it as likely being a 60mm mortar. “It looks like one man is using the mortar tube, which is relatively unusual. Normally, it’s at least a two or three-man team. And the munition looks light green in colour with a sort of light metal-coloured fuse and light silvery tail fins,” he said. “It’s definitely a small calibre mortar, which is a mainstay in military forces. This appears to be military/official manufacture rather than improvised,” Matthewson told Bellingcat.

Which Groups Use the Weapons?

From the data collected from 2023 and 2024, Bellingcat found that many rifles in the images have different furniture and display cloth wraps, improvised slings, aftermarket optics, even taped-on foregrips.

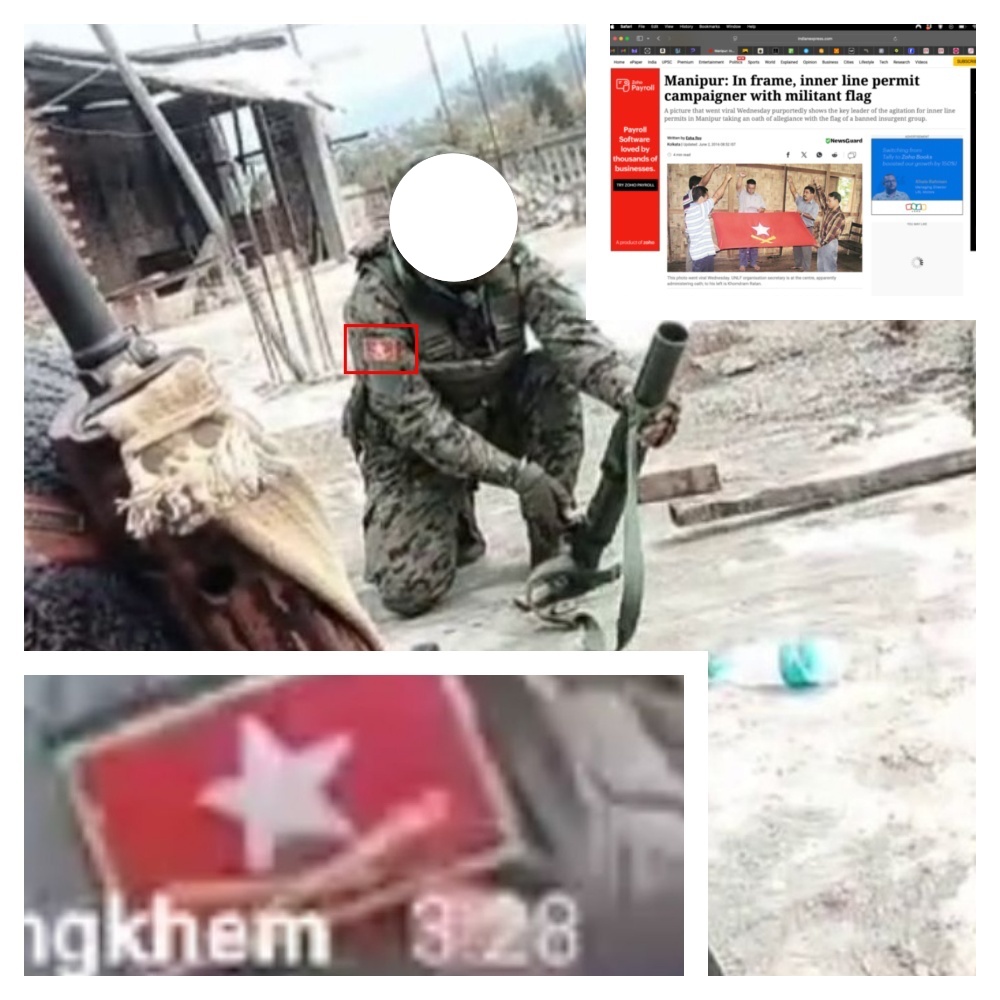

The next step is to identify the various groups in the pictures. Analysing symbols is a good way to do that. For example, we know that the Saipikhup is the traditional weave of the Kukis. It symbolises heritage and identity and is often worn during important occasions. We also found images of Kuki militants wearing this handwoven shawl (saipikhup) belonging to the Thadou indigenous tribe.

Their fatigues bear the insignia of the President faction of the Kuki National Front, which has been accused of attacking paramilitary security forces. Meanwhile, the same group in the image brandishes AR-pattern and INSAS rifles. The INSAS rifle is an Indian police or military issue, matching reported looting from armouries. Several weapons in the image were also heavily customised, consistent with militia or irregular combatant practices.

Other images also offer clues.

The Kangleipak is a seven-colour flag usually brandished by the AT.

Bellingcat also identified the AT’s commander-in-chief, Korounganba Khuman, in the photos and videos. He actively posts on his Facebook profile and has been widely covered by the local and national press.

News outlets are also valuable sources of information. They might contain images of symbols such as flags, which you can then search for on social media. In one of the videos, we identified militants speaking Meitei Lon, a language used by Arambai Tenggol and militant groups like the UNLF, preparing to fire a mortar projectile from a mortar. Their fatigues bore an insignia that we matched to the UNLF armed group using reverse image search, which led us to a news story featuring the group’s flag as the lead image.

Praveen Donthi, a senior analyst with the Crisis Group who visited Manipur last year during elections, told Bellingcat that though he hadn’t seen arms on any of the aforementioned Kuki Zo militant groups, he had seen INSAS rifles, automatics and double-barrel shotguns being wielded by several young men in the Imphal valley.

“I saw these young men who must have been in their early teens to early twenties when I’d gone to meet Meitei Leepun [a Hindu right-wing activist group] first wielding what looked like state-issued weapons,” he said. “Then later, they replaced it with double-barreled guns. But their leader [Pramot Singh] was openly carrying a pistol in his holster when he came to meet me,” Donthi explained.

Donthi, a former journalist who has reported from conflict zones in Kashmir and Chhattisgarh in India, said he was struck by the young men who were heavily armed in a volatile environment without any evident goal or political ideology guiding them.

Weapons Looted: Where Did They End Up?

When investigating conflicts, identifying the origin of weapons is one of the most difficult tasks, particularly in regions plagued by misinformation or a lack of reliable data. This is the case in Manipur.

Of the 6,000 firearms and ammunition looted from state police armouries mentioned earlier, about half of the weapons have been recovered to date. Around 1,200 matched serial numbers from official inventories, according to reports. Of the weapons recovered, approximately 800 sophisticated ones likely originated outside the state, and 600 were crude, locally produced firearms.

Subscribe to the Bellingcat newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for first access to our published content and events that our staff and contributors are involved with, including interviews and training workshops.

The largest surrender of weapons took place in February and March when more than 1,000 weapons were reportedly surrendered, with more than half from the Meitei-dominated valley districts, where a majority of the weapons were looted. The largest cache was surrendered on February 27 by the Arambai Tenggol (AT). However, the state police is yet to complete categorising the details of the weapons and ammunition surrendered between February 20 and March 6 against the inventory of weapons looted from the state armouries.

Bellingcat requested official data from the Manipur police on surrendered weapons matched against serial numbers from official inventories, but had received no response by the time of publication.

Instead, we decided to see what we could find by using open sources. First, we scraped the state police force’s official X profile (@manipur_police) from Sept. 10, 2023, until June 14, 2025. We did it manually and using Meltwater – a social media monitoring tool.

We dug deeper into media reports, experts’ posts and research to understand what was being used locally. In the Manipur case, recovered firearms include locally manufactured bolt-action rifles, improvised mortars and weapons such as the “Pumpi” – a gun made from repurposed metallic electric poles. These are especially common in the hill areas where the Kuki Zo people live.

The heavy reliance on grenades and improvised explosives is consistent with the guerrilla-style, asymmetric engagements – hit-and-fades, booby-traps, and area denial – rather than large-scale firefights. The presence of multiple improvised munitions types reflects local workshops or village-level bomb-making, likely to supplement limited access to military-grade ordnance, consistent with media reporting on the same (see here and here).

Claims Over Weaponised Drones

In September last year, Indian media reported villagers in the valley district witnessing drones allegedly dropping as many as 50 bombs. Kuki Zo village volunteers and insurgent groups were reported to have set up bunkers in the hills, much like their Meitei counterparts in the valley.

These claims were supported by a Manipur Police statement. The central counter terrorism law enforcement authority, the National Investigating Agency, which filed a case alleging weaponised drone attacks, told the Manipur High Court that Kuki militants dropped 40 drone bombs.

A source in the Defence Ministry told Indian news site The Print that the drone videos circulating online were from either Myanmar or Palestine. Many of the videos showed fertiliser drones, but these were deployed by the People’s Defence Forces in Myanmar, they added.

How Do You Investigate Potential Drone Usage With Open Source Tools?

The Manipur Police posted an image of a drone recovered in the Kangpokpi District, a day after the first set of attacks.

The first step is to identify the possible drone type. The easiest way is by using Google’s reverse image search engine. We identified the drone as commercial-grade, weighing approximately 181g. These carbon fibre lightweight drones, built for speed and agility with a payload capacity of up to 1.5kg, are widely available on the internet. Security sources told The Print that the bombs weighed 300-400g and were nine to 10 inches (23 to 25cm) in size.

After establishing the possible drone type, we can also examine the reported impact sites. Since we only have images of the attack sites shown in the media, we asked Andro Mathewson, a reputed munitions researcher and explosives expert completing his doctoral studies on weaponised drones in smaller conflicts at King’s College London, for help.

He told Bellingcat that in this situation, “the payload is probably quite small. So the damage won’t be extensive”.

“Some of the images that are shared in The Print report,” added Mathewson, “obviously show a lot of destruction, but a lot of it seems to be sort of secondary destruction from fires rather than from explosions itself”.

Nothing was visible that could specifically determine if drones were used to deploy munitions. The damage from a smaller payload like 400-600g of a grenade would not exceed more than 20 to 30m, according to Mathewson, adding that larger or heavier payloads are not typically seen among non-professional militaries.

The next step is to find out if the munitions have been adapted for drone deployment. Mathewson told Bellingcat that photos of drone parts published by the media were not consistent with munitions deployed by drones. Bellingcat was not able to independently confirm the source or authenticity of these photos.

“That shrapnel looks large, very thick, and very heavy, which is more consistent with larger artillery rounds or even small missiles,” he said. He also noted that the printed fin “looks quite small”.

“Fins made out of plastic are not likely to be attached to a much larger munition that’s produced that type of shrapnel,” he told Bellingcat, saying that “from the scale that we can get in those images, those don’t seem to add up to me”.

For future reference, when we asked Mathewson what to look out for to confirm the use of weaponised drones, he suggested two things. One would be to see and verify videos of drone strikes, either shot by other drones or on phones – something that is conspicuously missing from Manipur despite the authorities’ claims that there have been drone strikes, although there is plenty of online footage of other sophisticated weapons used there. Secondly, Mathewson also said it was worth looking out for 3D-printed munition parts, such as 3D-printed fins that are attached to conventional weapons.

“That’s not necessarily a guarantee, but it’s most closely associated with [modified drones] because the only reason you would attach fins to a grenade, for example, is to make them be dropped from drones,” he added.

Correction: This article has been updated after an image previously incorrectly stated members of the Kuki National Front were posing with AK-47s, M4 Carbines and M16 weapons. We also updated it to reflect errors in identifying the bolt action rifle, the FAL and 60mm commando-style mortar grenade. A section on chronolocation of this video was also removed, and a clarification was added that only the public iTrace dashboard was consulted, rather than cross-referenced with OSMP and the Small Arms Survey.

Additional reporting by Douminlien Haokip.

Pooja Chaudhuri, Claire Press and Gyula Csák contributed to this report for Bellingcat.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here and Mastodon here.