Untangling the Mystery of the World’s First Rooftop Solar Panel

In 1909, inventor George Cove posed in front of an early rooftop solar panel of his own design for a photograph. One hundred and ten years later, the resulting image was reprinted in the official journal of the US’ most prestigious research institute – but Cove was nowhere to be seen.

Using a range of sources such as newspaper archives and historic city maps, Bellingcat sought to establish the seeming mystery of Cove’s ‘disappearance’ from the photograph. This analysis of archival material from the pioneering days of solar energy tells a cautionary tale about the ease of misattributing historic photos.

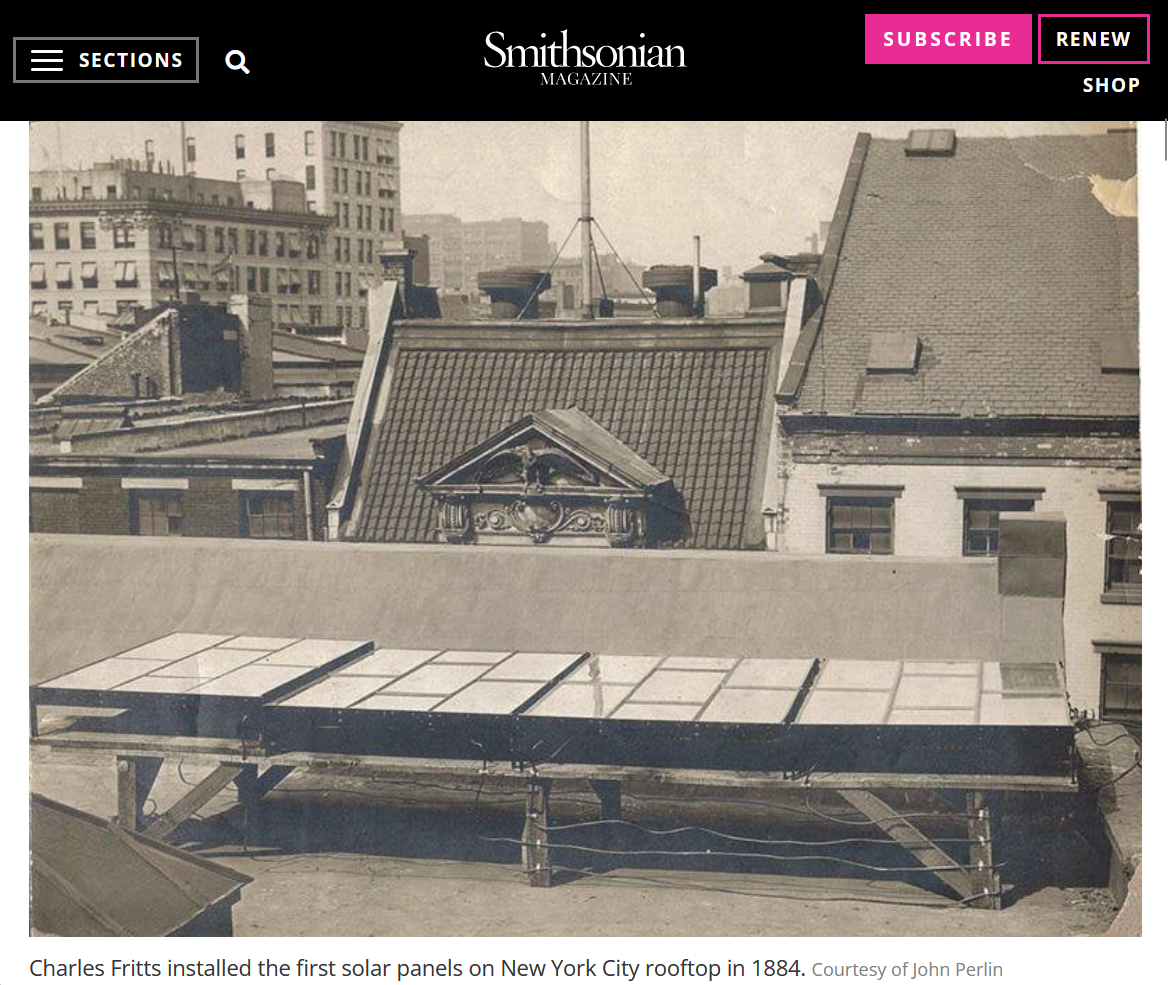

At the time of writing, a Google search for the term “first solar panel” yields an image of four panels purportedly installed on a New York City rooftop in 1884 by a man called Charles Fritts.

This image and accompanying description were published in Smithsonian Magazine in April 2019. The magazine is affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC — which describes itself as the world’s ‘largest museum and research complex’. The article in Smithsonian, which was authored and sponsored by the US Patent and Trademark Office, is currently cited by Wikipedia, 16 journal articles and numerous blogs and websites.

However, open source evidence indicates that the claim that Fritts installed these particular solar panels is false.

The suggestion that something was wrong was first raised in an article by Kris de Decker for Low-Tech Magazine in November 2021. The article investigates whether a man called George Cove had accidentally invented efficient photovoltaic panels 40 years before the creation of modern silicon solar panels.

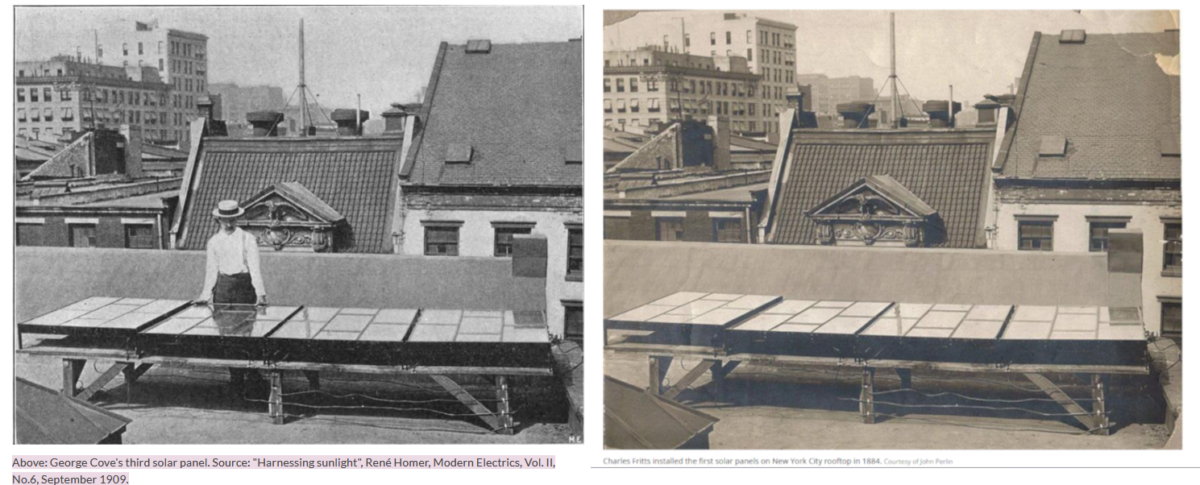

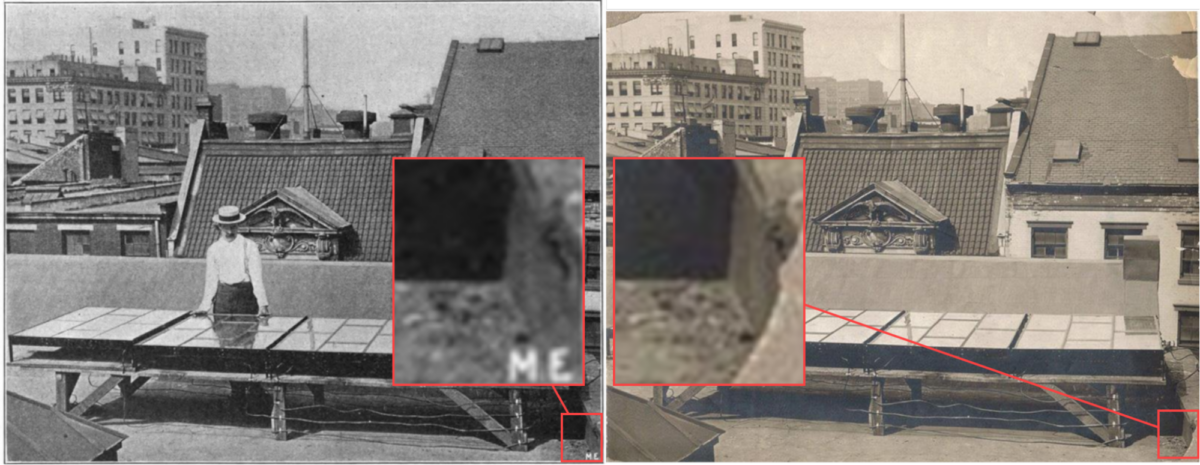

Accompanying De Decker’s article are several photos of a similar-looking device. One of the photos appears identical to Smithsonian’s photo, apart from one detail: A man is standing behind the panels.

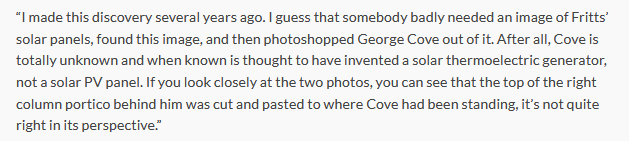

The article quotes a reader familiar with the topic, Philip Pesavento, who suggests that the photo that includes the man is the original photo. He also claims that someone might have edited the man out of the image and attributed the invention to Fritts instead:

A technical assessment of Fritts or Cove’s contributions to solar power is beyond the scope of this article. Both men are credited with making advances in the field — for example, Low-Tech notes Fritts constructed “the first photovoltaic module ever made, using selenium on a thin layer of gold.”

However, open source investigative techniques can at least establish whether this image has been misattributed.

So, has one of these photographs been altered? In attempting to determine the truth, it is necessary to trace both the origins of these images as far back as possible. Fortunately, both Smithsonian and Low-Tech magazines have included sources for their respective photos.

The Originals

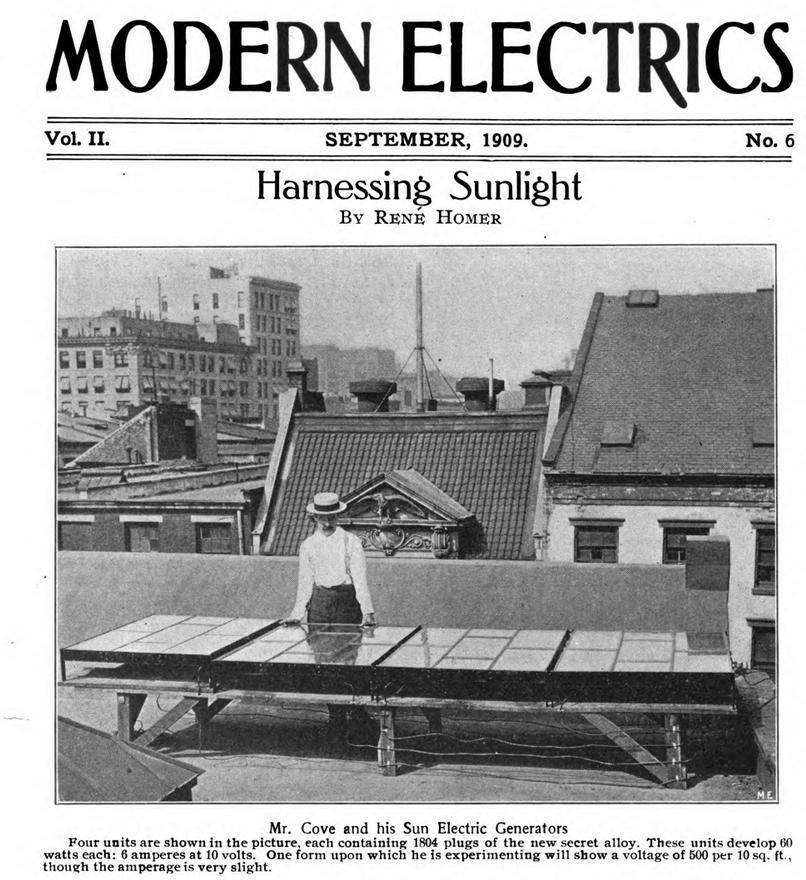

“It has been the contention of many eminent scientists during the past two centuries that the energy expended in any way upon the earth came originally from the sun.”

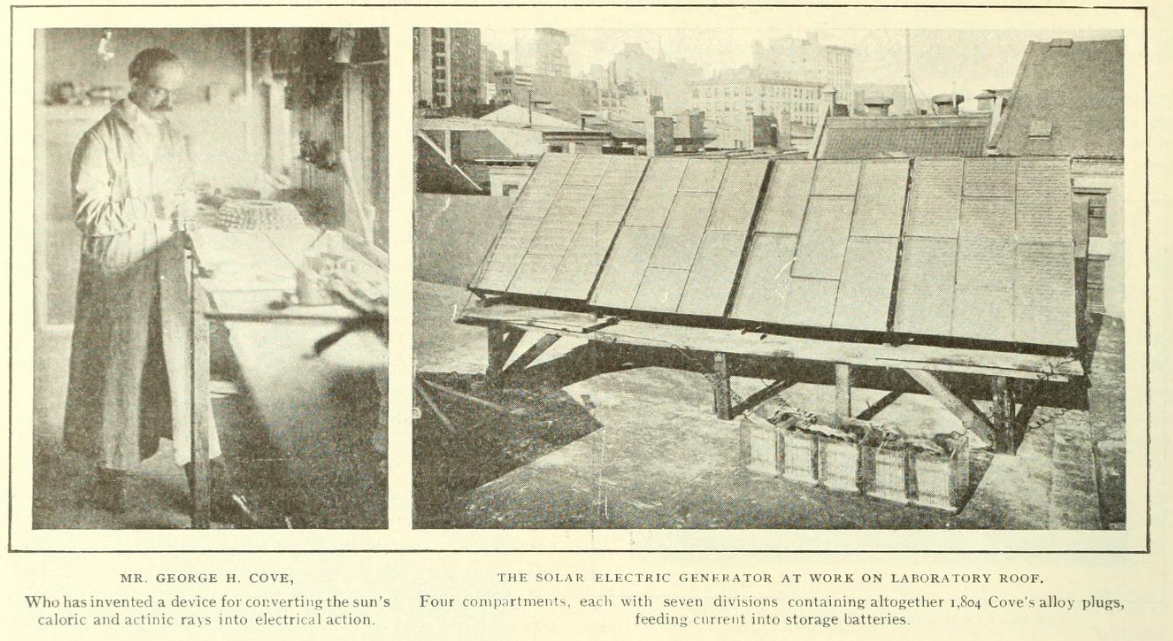

These are the first words of the opening article of the September 1909 issue of Modern Electrics, which Low-Tech Magazine cites as the source for its image of Cove. In this issue, the US magazine introduced a new invention: the Sun Electric Generator. The publication’s pages are filled with purported scientific advancements in areas such as tuberculosis treatment, firefighting techniques and the latest ‘flying machines’.

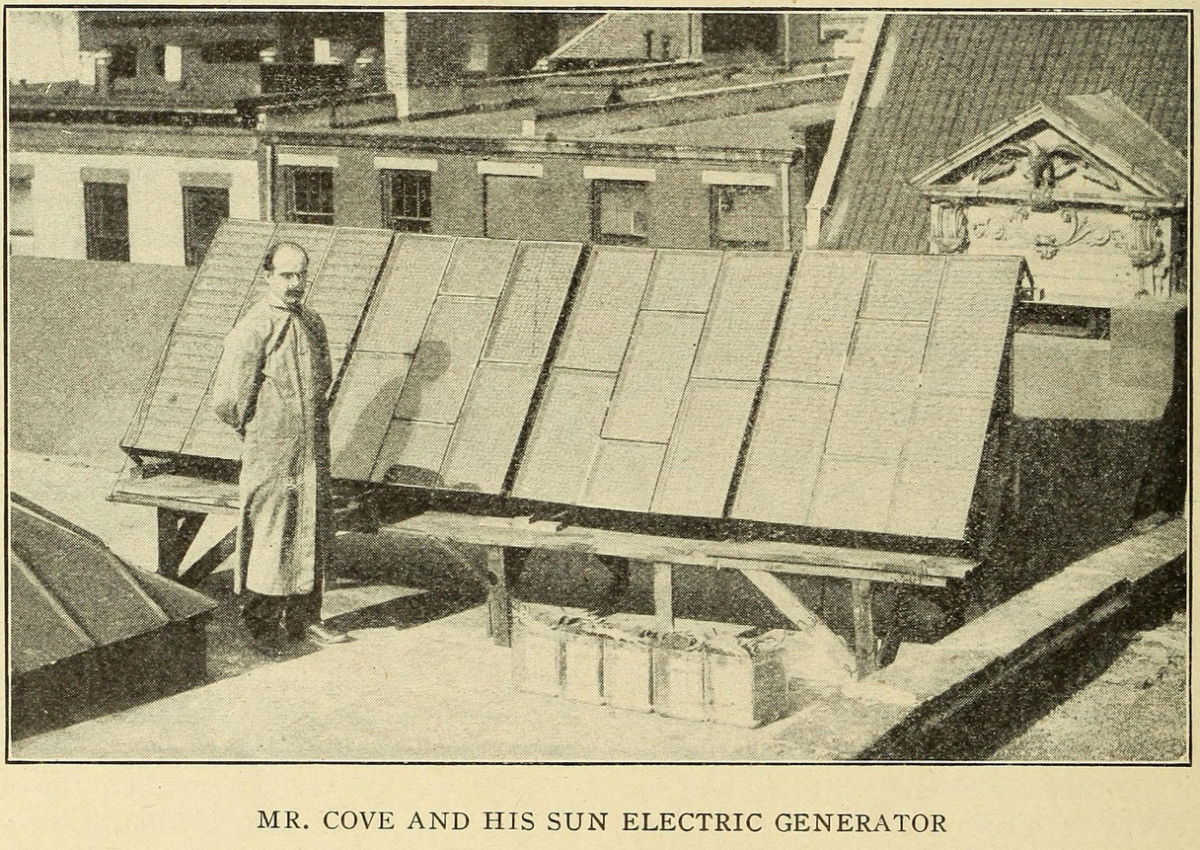

However, the ‘Harnessing Sunlight’ article took centre stage, featuring a photograph of inventor George Cove standing proudly behind his solar panels.

A copy of this magazine is held by the University of Michigan and can be found in digitised format on Google. This appears to be the first time the photo, titled “Mr. Cove and his Sun Electric Generators”, was published.

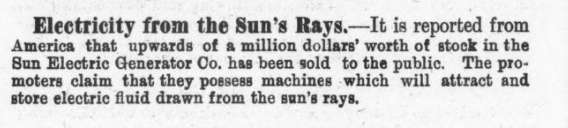

A search on Archive.org using the keyword ‘Sun Electric Generator’ reveals that several other US magazines from 1901-11 reported on the invention.

Right: The Literary Digest issue of December 18, 1909. ‘Electric Power from Solar Heat’.

These archived copies show Mr. Cove in multiple sources and photos and attribute the invention to him alone. However, Smithsonian’s photo of the solar panels on the rooftop without Mr. Cove cannot be found elsewhere online. This raises the question: how did the authors of the Smithsonian piece acquire this particular image?

The article in Smithsonian which attributes the installed solar panels to Fritts states that the image was provided “courtesy of John Perlin.”

Perlin, a researcher at the University of California, published the book “Let It Shine: The 6000-Year Story of Solar Energy” in 2013. He has used the photo to promote a lecture on the book.

Perlin’s book contains what seems to be the first publication of the photo later used in the article published in Smithsonian. Alongside it, he includes the caption “Charles Fritts put up the first photovoltaic array, in New York City in 1884”. This date and name of the inventor are different from those provided in Modern Electrics.

Unfortunately, the trail for this photo ends here, as no further sources are provided.

Can a comparison with the Modern Electrics image tell us something about the provenance of the image provided by Perlin?

A Closer Comparison

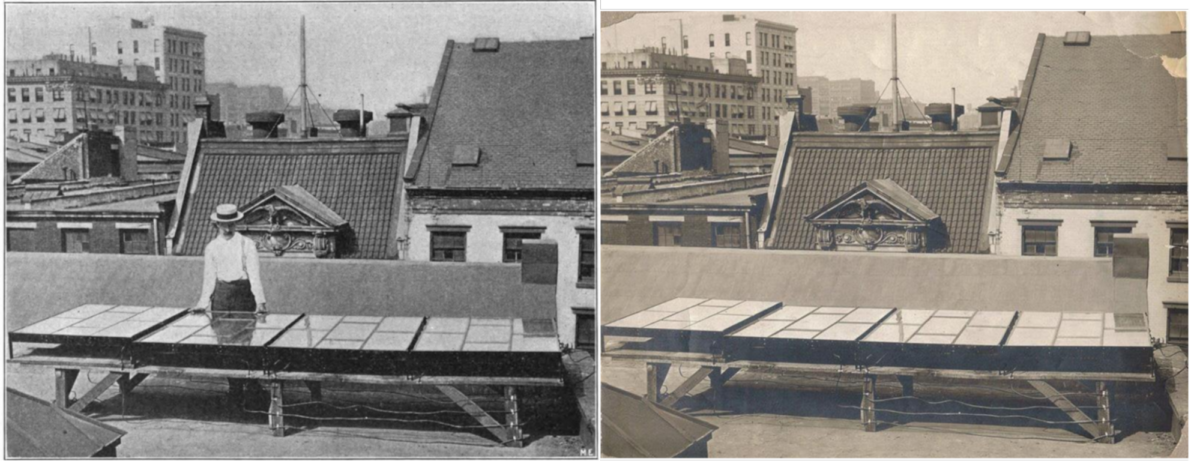

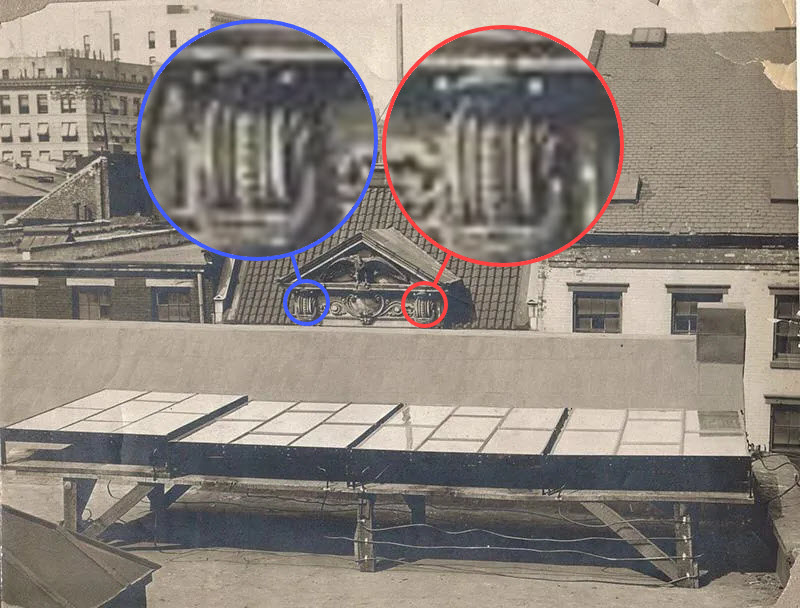

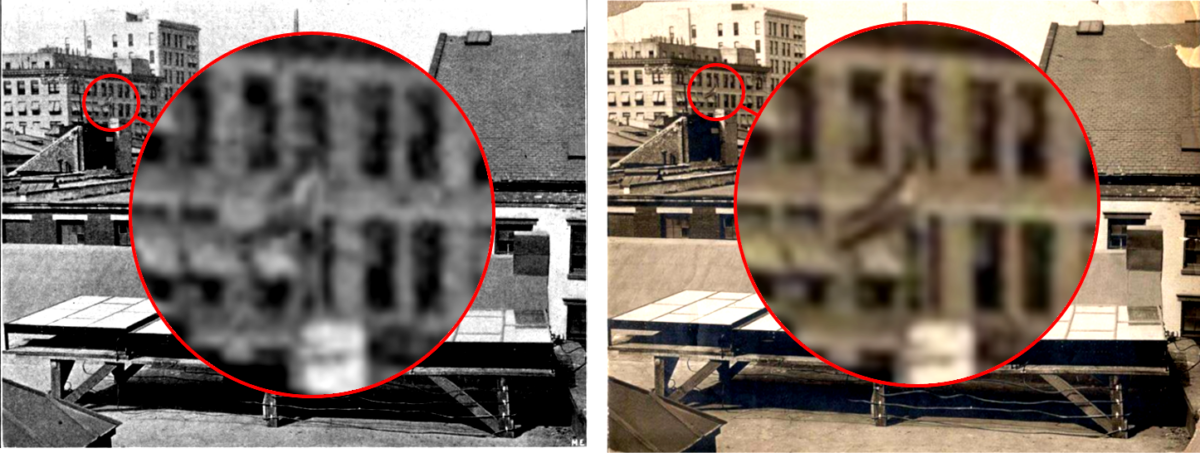

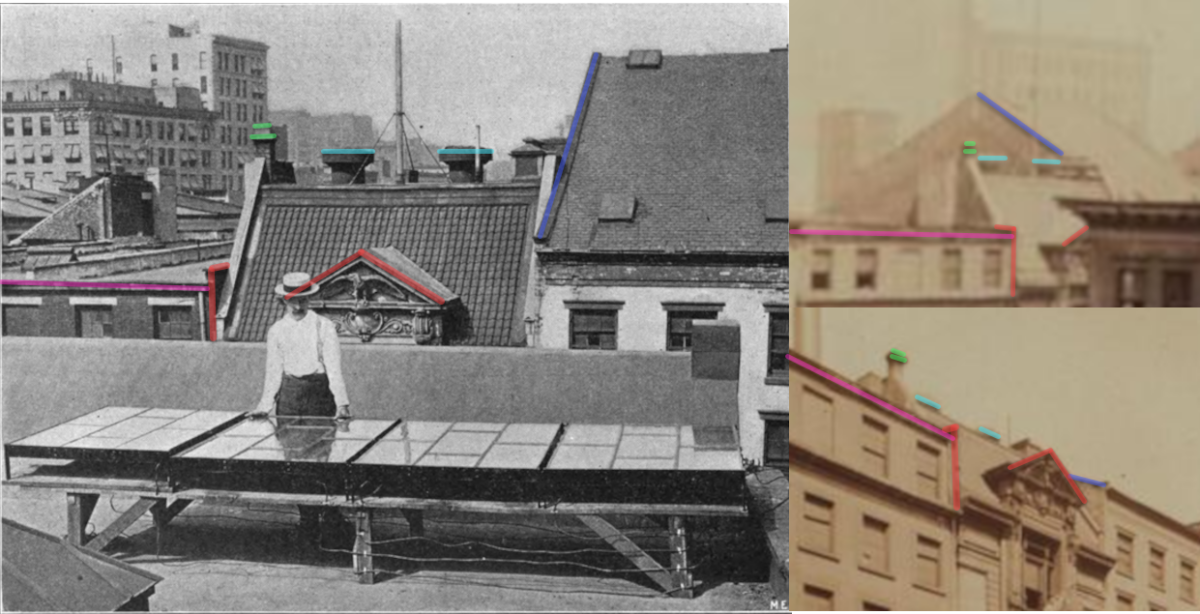

When comparing these two photos, it is apparent that the angles of all the buildings and objects appear exactly the same. If they are two separate photos, the camera has seemingly not moved an inch between taking them. The shadows are not noticeably different either. There is no change in the open and closed windows in the background building to the left, nor in the positions of the awnings over them.

Smithsonian’s photo is slightly smaller, has a higher resolution and a glare visible on the solar panel. It is also damaged, with tears and blotches visible in the corners.

This could be explained by the fact that when it was digitally archived, the Modern Electrics photo was scanned from an undamaged printed copy of the magazine. Smithsonian’s photo appears to be a ‘photo of a photo’ which was then published online. It cannot be determined which image was taken first.

Interestingly, the crop and the damage of Smithsonian’s photo have largely, but not entirely, obscured the image’s bottom right corner. In the Modern Electrics photo, this is where the initials “ME” appear — presumably the initials of the publication.

Removing clues that could lead to the source is a common tactic for those looking to spread disinformation. The low resolution of the photo would make it comparatively easier to manipulate.

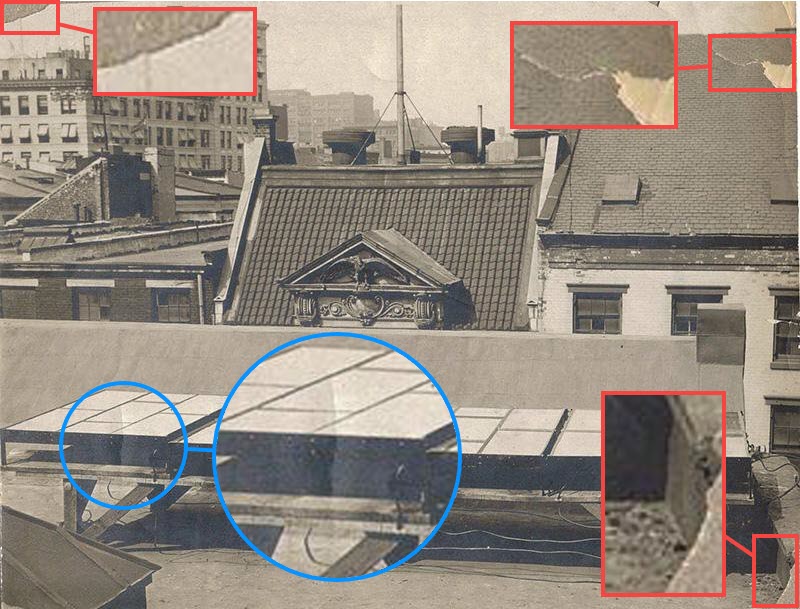

In contrast to the claim in the article from Low-Tech Magazine, it doesn’t look as if somebody deliberately airbrushed George Cove out of Smithsonian’s photo in order to attribute the invention to Fritts.

To understand why, let’s look at the top of the portico on the building behind the man in the photo.

There are no obvious signs of rudimentary photo manipulation, such as pasting parts of the photo on top of each other. Nor does using a tool like Forensically show any clear indication of image editing, although it should be stressed that only one such tool is not sufficient to conclusively rule in or out manipulation. In short, the two areas appear similar but are not copy-pasted.

A closer look suggests subtle differences in the background of both photos. Though the sun and shadows move slowly, the wind may have played a role here. A flag visible in the background of the Modern Electrics photo appears to be in a different position on Smithsonian’s photo.

It is possible that the photographer simply took two separate photos — one with Cove and one without, leaving his camera in the same position. Not enough time had passed in between for shadows to noticeably move, but the wind did move the flag.

This is a plausible explanation for the difference but it cannot be ruled out that low resolution and damage to Smithsonian’s photo, rather than the wind, may have also accounted for this discrepancy in the appearance of the flags.

Although there’s no evidence of image tampering, there is another way to demonstrate that the photo is linked to Cove and not Fritts.

Though he bears a resemblance to the George Cove seen in the newspaper articles from the early 20th century, we cannot conclusively determine through open sources alone whether the man in the Modern Electrics photo is George Cove. However, we can confirm that the photo was taken on George Cove’s rooftop through geolocation.

A New York Times article from 1911 on the demise of Cove’s experiments mentions that his laboratory was situated at 118 Maiden Lane, New York. NYC Then & Now provides an aerial overview of the street in 1924. The historical photography website OldNYC gives us various pictures from the same street around the turn of the 19th century.

The same buildings visible from Cove’s laboratory rooftop can be also seen in these old photos from Maiden Lane as well:

A Tale of Two Inventors

The ample news reports and additional photos from the 1990s suggest that the man is George Cove standing on his rooftop. The geolocation confirmed that the photographed rooftop indeed belonged to the address of Cove’s laboratory.

But contrary to what was argued in Low-Tech Magazine, no photoshopping was involved in the picture published by Smithsonian. Smithsonian Magazine’s editorial director, who noted that the piece came from a sponsored partner, told Bellingcat in an email that he was not aware of any inaccuracies in the article. One of the co-authors of the piece, Elizabeth Chu, said she was not aware of George Cove having installed the panels.

The photo used by Smithsonian could not be found in any of the archived published newspapers or magazines at that time. How then, did John Perlin come across this photo, and why did he choose this one for his book and supply it to Smithsonian?

After Bellingcat reached out, John Perlin wrote that, after publishing a book on the history of photovoltaics, he had been sent a postcard with the photo in question, depicting the array. Perlin told Bellingcat that an antiquarian had verified the accuracy of the photo. On the back, he continued, typescript had clearly indicated that the panels were put up by Charles Fritts in 1884 – the typescript, he continued, was in mass use in the US by the 1880s.

“If you know the life history of Charles Fritts, as I do, Cove might have become the owner of Fritts’ laboratory and the array in the picture due to an unfortunate turn of events in Fritts’ life,” wrote Perlin in his reply to Bellingcat. “Sometime in the 1890s he suffered a stroke and could no longer work at his profession”, he added, stressing that Cove’s acquisition of Fritts’ laboratory was only speculation.

But that sequence of events now appears unlikely; the photo was taken nearly 20 years later.

The two men’s work was separated by time. The Newspaper articles of Cove’s invention were published in 1909, while Fritts was reportedly active in the 1880s and 1890s.

Moreover, the two men’s work in New York was also separated by space. Newspaper articles from the period when Fritts was active indicate that his laboratory was situated at 42 Nassau Street. This is three blocks away from 118 Maiden Lane, which contemporary reporting states as the address of Cove’s laboratory.

Perlin states that the technology of the two devices was completely different. Yet in the photos which depict the inventions of Cove and Fritts respectively, exactly the same device can be clearly seen.

“The Cove device offered nothing new. It had no relationship to photovoltaics, as it depended on the heat of the sun while solar cells produce their electricity from solar light”, explained Perlin. “Charles Fritts, in contrast, built the first photovoltaic module… Cove’s work led to a technological cul-de-sac”, Perlin concluded.

Perlin told Bellingcat that it took the US Patent Office 16 years to approve Fritts’ application for a patent and that the inventor died several years before it was granted.

What happened to Cove?

Dennis Bartels, an anthropologist at Memorial University in Newfoundland, Canada, investigated Cove’s life. He explored the possibility of the inventor Thomas Edison and/or Standard Oil suppressing Cove’s invention as it might have threatened their business models.

Due to the publicity of Cove’s company, he was frequently mentioned by contemporary newspapers and magazines. Archive.org can be used to search these.

In January 1910, an article appeared that was critical of Cove’s invention, claiming there would be “hardly a commercial possibility in sun power development” without cheap power storage. This, however, did not stop investors. In June that year, it was reported that Cove’s company sold stock worth over US$1 million (equivalent of approximately $31 million today) to the public.

The success of his Sun Electric Generator company did not last long. Cove’s story rapidly took a bizarre turn.

First, in the same year his company successfully raised the money, Cove disappeared for a while. In a letter, he said he had been “kidnapped by a number of capitalists, who sought to wrest from him the secret of his plan to generate electricity by concentrating the rays of the sun.”

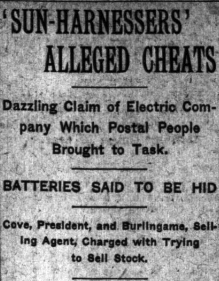

Cove’s company, which by July 1911 had gathered $5 million (equivalent of approximately $155 million today), also came under criticism for the way it was financed. According to the United States Investor, Cove’s company was being supported by a man called Elmer Ellsworth Burlingame – who had become notorious for selling fraudulent stock in “get-rich-quick fakes”.

News reports began circulating about a statement made by a former employee of Cove, who claimed that the rooftop generators were not actually charging batteries. Reportedly, Cove’s company had also withdrawn from New York and moved to New Jersey.

Cove and Burlingame were arrested only a few months later, in August 1911 his rooftop installation was not supplying electricity on its own, but was “found to be connected by concealed wires” with the building’s electrical network (‘Edison Wires’).

“Was George Cove a charlatan? Was he the victim of one? Or was his reputation destroyed because the solar electric generator threatened other companies’ interests?” asked De Decker in his article for Low-Tech Magazine.

Though these questions remain unanswered, the available evidence shows that the device on that rooftop belonged to Cove, the man standing behind it in the photo.

Correction: This article was updated on 17 August 2023 to correct the dates in the introductory paragraph.

Logan Williams and Timmi Allen contributed research. The author would like to thank Giovanni Lostumbo for bringing the topic to his attention.