Boris Nemtsov Tailed by FSB Squad Prior to 2015 Murder

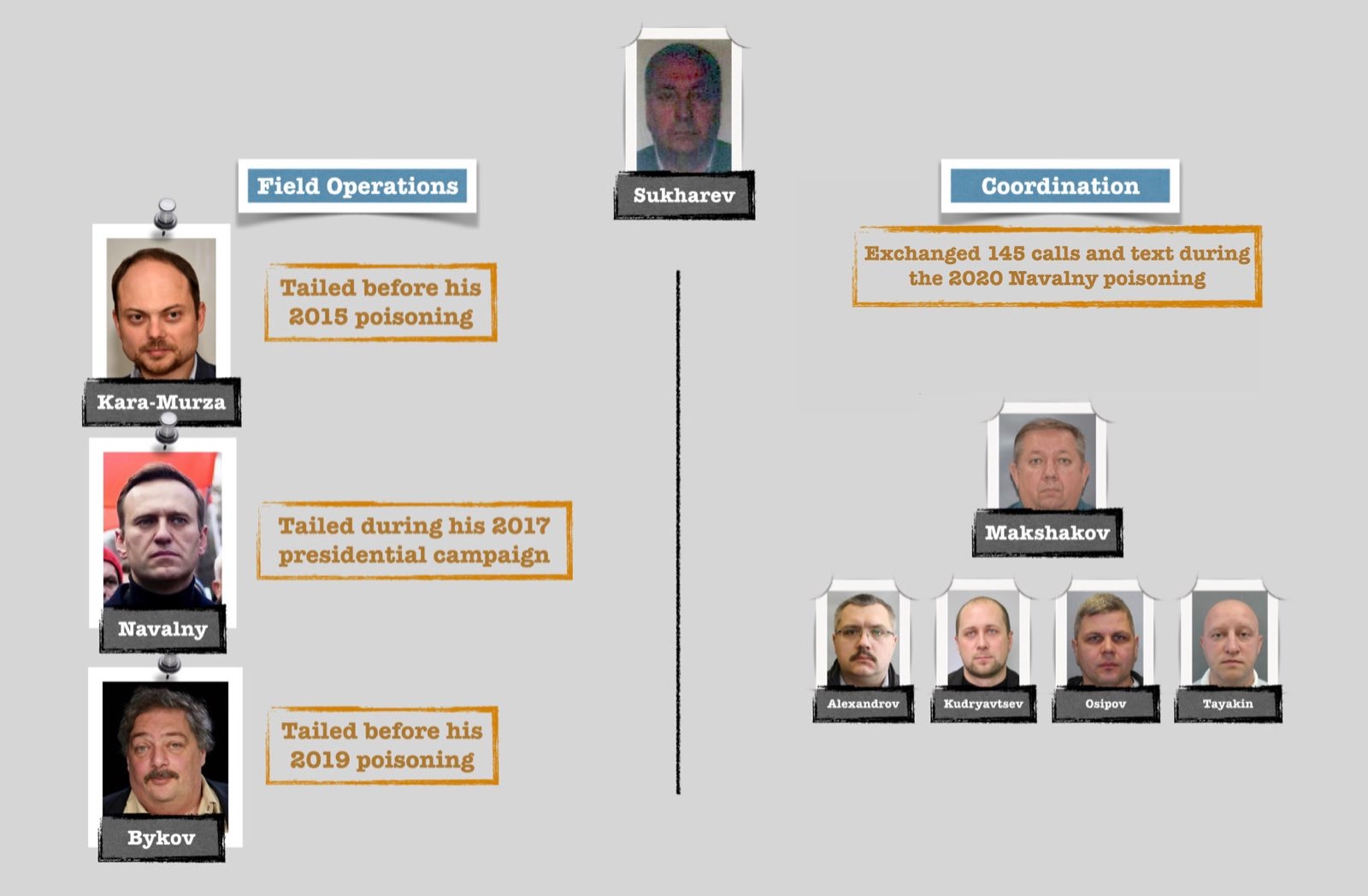

- Previously, Bellingcat and partners discovered that a secret FSB squad had followed Russian opposition figure Alexey Navalny during his presidential campaign in 2017, and in the days and months before he was poisoned in 2020. The same squad had also tailed Vladimir Kara-Murza and Dmitry Bykov in the days and months before their suspected poisonings.

- Travel data also showed members of the same unit appeared to have tracked at least three other activists who later died in mysterious circumstances.

- According to our investigations, the squad was comprised of chemical weapons experts from the FSB’s Criminalistics Institute and officers from the Directorate for the Protection of Constitutional Order of the FSB’s Second Service. The latter is described by the US Treasury as “managing internal political threats on behalf of the Kremlin.”

- Bellingcat subsequently identified the prominent role played by FSB officer Valery Sukharev in the operations against Navalny, Kara-Murza and Dmitry Bykov. Travel data shows he trailed Navalny during his 2017 presidential campaign, Kara-Murza immediately before his first apparent poisoning and Bykov for an entire year before he fell mysteriously ill with symptoms consistent with those experienced by Navalny and Kara-Murza.

- Sukharev also seems to have played a coordinating role in Navalny’s poisoning — exchanging over a hundred phone calls with five FSB agents implicated in the assassination attempt — including with one of the leaders of the operation Stanislav Makshakov.

An investigation by Bellingcat, The Insider and the BBC has now discovered that in the days and months prior to his assassination in 2015, Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov was tailed by members of the same assassination squad that would subsequently follow Kara-Murza, Bykov and Navalny.

Nemtsov was once the man many thought would succeed Boris Yeltsin until Vladimir Putin was appointed acting president in December 1999. He became a thorn in the Kremlin’s side over the subsequent decade. He advocated international sanctions against Russia’s political leadership. He opposed the annexation of Crimea and demanded an independent investigation into the downing of Malaysian flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine.

In the years immediately preceding his death, Nemtsov was one of Putin’s fiercest critics — and among the most prominent.

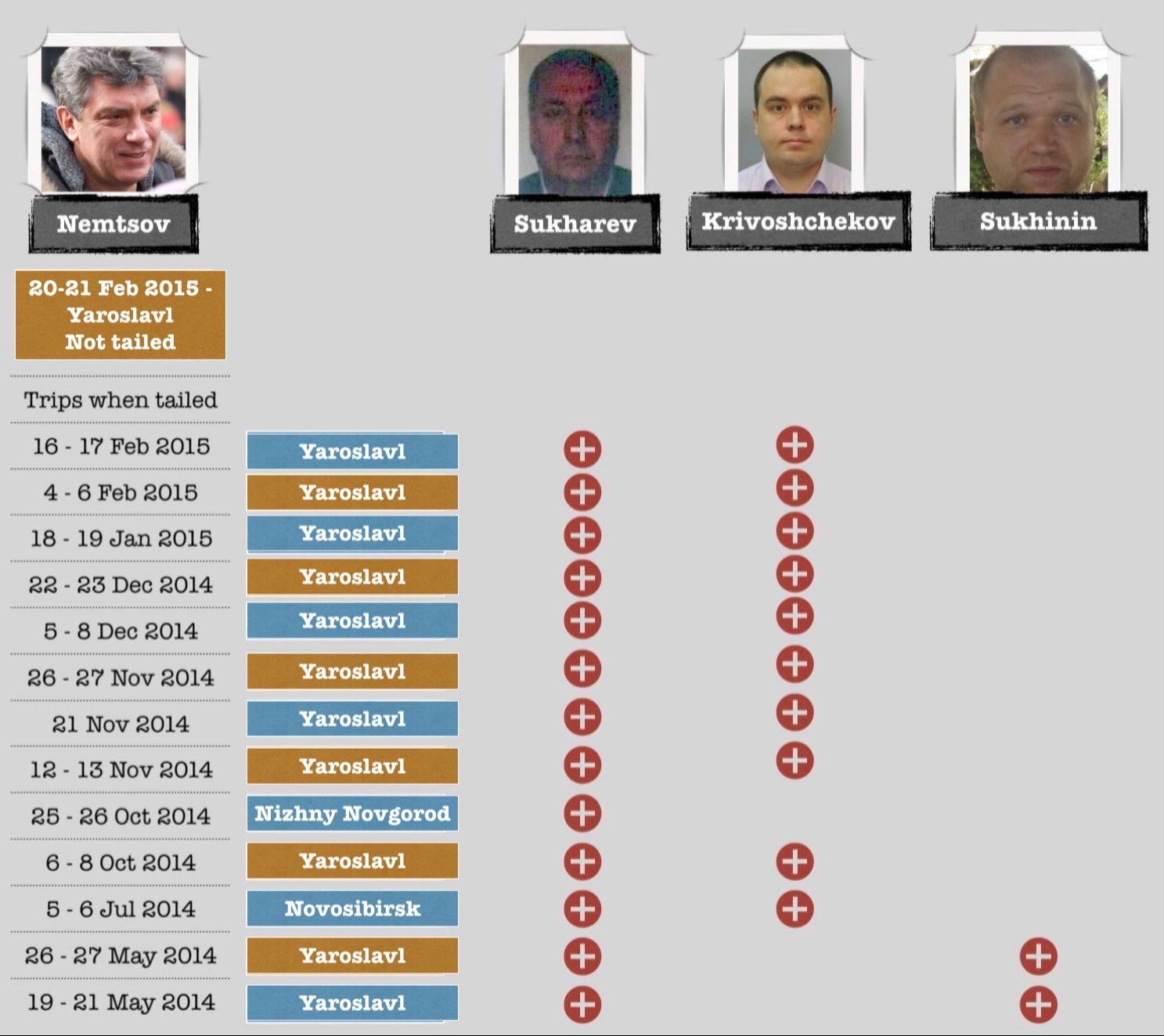

For 10 months, the opposition figure was tailed by members of the FSB’s Second Service. These agents stopped following him just one trip prior to Nemtsov’s execution by pistol in Moscow on 27 February 2015.

Zaur Dadayev, a former Chechen security officer close to Chechnya’s ruler Ramzan Kadyrov, was convicted of the murder by a Russian military court. Despite an initial confession in pre-trial proceedings that he subsequently said was made under duress, Dadayev has maintained that he and five other Chechens tailed Nemtsov for months but did not commit the murder. Russian human rights defenders have suggested that Dadayev was tortured in pre-trial detention. Neither the official investigation nor trial established why Nemtsov had been killed, nor who had ordered the assassination.

The precise motive for that assassination remains a mystery to this day. The accused initially claimed that the Chechen group had committed the murder as revenge for Nemtsov supporting the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo which had been attacked by Islamist militants. This pretext disintegrated after it was found that the suspected killers began following Nemtsov before he had made any statements about Charlie Hebdo.

Much remains unclear. But what can now be demonstrated is that long before the Chechen group came to Moscow to surveil Nemtsov, he had been watched for months by members of a secretive FSB unit that has since been implicated in poisoning several opposition figures.

The FSB tailing team followed Nemtsov on all his trips to regions in Russia between May 2014 and February 2015. They followed a similar pattern to the tailing of other poisoning victims: they usually arrived hours or a day before Nemtsov and left shortly before or after him. Notably, during the last trip from Moscow to Yaroslavl, where Nemtsov served as a local city council member, the FSB officers did not tail him. Days later, he was killed in Moscow.

These new findings raise fresh questions about the circumstances around Boris Nemtsov’s death, including whether the convicted Chechens — in the event they were indeed the assassins — had acted independently of Russia’s security apparatus. New doubts also emerge about the impartiality of the official investigation. A large part of the prosecution’s case relied upon DNA comparisons performed by the Criminalistics Institute — the same FSB department that collaborated with Nemtsov’s tailers in the poisoning operations against other opposition figures.

A Note on Bellingcat’s Methodology

Once again, our investigation uses travel data, phone records, and other public information about Russian citizens which is obtainable through Russia’s black market for data or features in leaked databases. This practice is known as ‘probiv’, which roughly translates to ‘lookup’ in Russian, and is widely used by investigative journalists, employers and authorities alike, albeit for very different purposes.

The methodology follows the pattern outlined in our Navalny investigation, and it has been verified by cross-checking it with multiple data sources. Further detail on this methodology can be found here.

Once we established the existence of a unit that tracked Navalny, we only had to analyse the old travel data of those same FSB operatives to find matches with other known poisoning attempts or deaths due to mysterious circumstances.

Thirteen Coincidences

Travel data obtained by Bellingcat shows that Nemtsov was followed on 13 return journeys by FSB officer Valery Sukharev, who in each case was accompanied by a second FSB operative. On the first two tailing trips — both to Yaroslavl — Sukharev was accompanied by Dmitry Sukhinin, a newly-uncovered FSB operative who has a background in chemistry and cryptography. On the next 10 overlapping trips — beginning with a 5 July 2014 round-trip to Novosibirsk — Sukharev was accompanied by Alexey Krivoshchekov, another known FSB operative who was subsequently implicated in the operation to poison Alexey Navalny.

There is no evidence that Sukharev, Krivoshchekov or Sukhinin were involved in Nemtsov’s murder. The method used to assassinate Nemtsov — shots from a pistol — also differs from the modus operandi later employed by these specialist FSB officers in targeting the likes of Navalny with poison. Phone records from this period are no longer accessible, and we cannot establish the officers’ whereabouts on the day of the assassination, nor whether they were in communication with the group of convicted Chechens.

It is notable, however, that the FSB squad stopped following Nemtsov on 17 February 2015, after an uninterrupted streak of 13 tailing trips. Nemtsov travelled to Yaroslvavl seemingly without a tail between 21 and 22 February. Just one week later he was shot dead.

The Nemtsov and Kara-Murza Switch

The motivation for the continuous long-term tailing of Nemtsov by a squad linked to subsequent poisoning attempts, but without an apparent plan to poison him, is not clear.

It would seem implausible that the squad of three operatives from the Directorate for the Protection of the Constitution were tasked with simply tailing and surveilling Nemtsov, as such a goal would conceivably be better achieved by a larger number of FSB officers taking turns to monitor their subject. Surveillance by the same officers over an extended period would increase the risk of them becoming conspicuous and potentially being noticed by the target.

In previously disclosed poisoning operations, members of the Directorate began tailing their target before later being joined by chemical weapons specialists from the Criminalistics Institute. Such an approach would be consistent with the initial group establishing the target’s routine during trips outside of Moscow, before being joined by their colleagues with expertise in administering chemical weapons. The absence of chemical weapons experts from the Criminalistics Institute on any of the tailing trips for Nemtsov may suggest that the intent was never to poison him, or that his routine identified during the tailing trips was unsuitable for such an operation.

It is notable that on the initial two tailing trips — both in May 2014 — one of the FSB operatives, Dmitry Sukhinin, was an FSB expert in cryptography and IT. In investigating Navalny’s poisoning, Bellingcat discovered that on at least two of his trips — to Kaliningrad in July 2020 and Tomsk in August 2020 — security cameras were disabled and, at least in Kaliningrad, surveillance equipment was installed in the hotel room prior to Navalny’s arrival. While Nemtsov rented an apartment in Yaroslavl, it is not known if this was monitored.

Travel data also shows that when the FSB squad stopped tailing Nemtsov on his trips out of Moscow, they immediately started following Nemtsov’s protégé Vladimir Kara-Murza. The first instance of a tail on Kara-Murza occurred on 25 February, two days prior to Nemtsov’s murder.

Both Nemtsov and Kara-Murza were outspoken critics of the Russian president and founding members of a united opposition initiative that sought to challenge Putin’s rule.

The pair were also prominent backers of the Magnitsky Act, a US law that allows the country to sanction human rights abusers internationally and which initially sought to target Russian officials deemed responsible for the mistreatment and death of the whistleblower Sergei Magnitsky.

Kara-Murza would initially be followed by members of the Directorate. Among them was Sukharev, who was later joined by a chemical weapons expert between 2015 and 2017. During this period, Kara-Murza would suffer two medical emergencies, both of which left him in a coma and with severe shutdown of his vital functions. Kara-Murza suspected he had been poisoned as retaliation for his political activities after the Russian authorities declined to initiate criminal proceedings into either case.

Two Russian hospital reports and three international examinations concluded that the incidents were caused by intoxication with an unidentified substance. The exact cause and source of the poisonings has remained a mystery and it only became publicly known Kara-Murza had been tailed by members of the Criminalistics Institute and FSB Second Service when Bellingcat and partners reported on the case in February 2021.

Nemtsov’s Shadow

The full data on Nemtsov’s movements show that he was tailed by the FSB’s Second Service, primarily by Sukharev, between 19 May 2014 and 17 February 2015.

The date of the first known tailing event was not long after Nemtsov and Kara-Murza had been active in lobbying the US government to add members of Vladimir Putin’s inner circle to existing sanctions lists. Several new names were added in March 2014, just two months before the tailing of Nemtsov began.

The first time the FSB team, composed of Sukharev and Sukhinin, followed Nemtsov was on 19 May 2014.

At 13.35 on this date, Nemtsov set off from Moscow’s Yaroslavsky railway station and headed to Yaroslavl, roughly 270 kilometres away, where he was due to attend a meeting at the local parliament. Sukharev and Sukhinin followed on another train, arriving exactly 25 minutes after Nemtsov.

A similar pattern of tailing occurred throughout the autumn and winter of 2014. However, one significant difference was that on all trips from early July 2014, Sukharev travelled with the other FSB operative, Alexey Krivoshchekov, when shadowing Nemtsov. It appears from booking data reviewed by Bellingcat that Sukharev knew Nemtsov’s plans in advance. He often arrived in the city in the minutes or hours before Nemtsov.

This is consistent with methods and capabilities which this FSB team would use to trail opposition figures in subsequent years, as observed in other Bellingcat investigations into the poisoning of Navalny and the suspected poisonings of Kara-Murza and Bykov.

Nemtsov took only one flight in the period when data shows he was being followed by the FSB: a single trip to Novosibirsk in July 2014. On this occasion, Sukharev was also accompanied by Krivoshchekov.

The close interest the two agents took in Nemtsov’s flight to Novosibirsk is emphasised by the time of the bookings.

Nemtsov reserved his tickets on 2 July at exactly 10 minutes past midnight. Both Sukharev and Krivoshchekov made their bookings just 10 minutes later at 00:20, travel data shows.

The two agents flew to Novosibirsk on the same day as Nemtsov, July 4, arriving a few hours ahead of the opposition politician. They then left Novosibirsk on July 6, an hour before Nemtsov was due to depart.

Nemtsov was in Novosibirsk to present a report on corruption in Russia’s state-owned energy giant, Gazprom. The movements of Sukharev and Krivoshchekov within Novosibirsk during these two days is currently not known.

The Significance of Nemtsov’s Shadows

Valery Sukharev, aka Nikolay Gorokhov

Sukharev is no ordinary FSB officer and his presence as ‘Nemtsov’s shadow’ is hard to explain away as simply the kind of political surveillance that may be expected in Russia, and which Vladimir Putin acknowledged was used against Alexey Navalny in 2020.

Based on an analysis of his travel and communication patterns, Sukharev appears to be the seniormost FSB officer involved with tracking Russian opposition figures who have subsequently been poisoned or been taken mysteriously ill with poison-like symptoms in recent years.

Sukharev tailed Vladimir Kara-Murza in 2015 and shadowed him on a trip to Kazan just two days before his first apparent poisoning in May 2015.

After assuming a cover identity as Nikolay Gorokhov, he tailed Navalny on most of his 2017 presidential campaign trips, following the opposition leader to a total of 18 destinations across Russia. Sukharev then used the same cover identity to tail Dmitry Bykov in 2018 and 2019. Bykov fell into a coma after being poisoned during one of his trips outside Moscow in April 2019.

In the two weeks leading up to Navalny’s poisoning in August 2020, Sukharev made dozens of calls to FSB officers linked to the operation. These included the chief of the FSB’s Technical-Scientific Service, Vladimir Bogdanov, and the deputy chief of the Criminalistics Institute, Stanislav Makshakov. Both Bogdanov and Makshakov were linked to the poisoning of Alexey Navalny and were sanctioned by the US and UK authorities.

Sukharev appears to be the seniormost FSB officer involved with tracking Russian opposition figures who have subsequently been poisoned or been taken mysteriously ill with poison-like symptoms in recent years.

He also called three operatives who flew alongside Navalny to Novosibirsk and Tomsk, or travelled to Omsk to destroy evidence of the Novichok administered on him. These men were Ivan Osipov, Alexey Alexandrov and Konstantin Kudryavtsev. Finally, Sukharev exchanged over 40 calls and texts with Oleg Tayakin, who coordinated the poisoning operations from Moscow and gained international fame by slamming his front door on CNN’s Clarissa Ward after she confronted him about the Navalny poisoning operation in December 2020.

There is scant information on Sukharev in public sources, with the only open source reference to him being that he was entitled to special state benefits in a leaked 2008 Moscow residential database reviewed by Bellingcat. Special state benefits are usually afforded to decorated special services or military officers as well as to veterans from Russia’s wars in Chechnya or Georgia.

Alexey Krivoshchekov

Krivoshchekov also appears to be part of the FSB’s Second Service based on a multitude of joint travel bookings with known members of that department. His telephone communication pattern implies that, like Sukharev, he was also in a supervisory role over the operatives from the Criminalistics Institute during the poisoning operation against Alexey Navalny in 2020. For example, in the two weeks before Navalny’s fateful trip to Novosibirsk and Tomsk where he would be poisoned, Krivoshchekov made 24 phone calls to Ivan Osipov, one of the operatives who — according to our findings and the inadvertent confession by FSB operative Konstantin Kudryavtsev — was responsible for administering the poison on Navalny’s clothes. In the same period, Krivoshchekov also had 38 phone interactions with the chemical weapons specialist Stanislav Makshakov, who supervised the poisoning team from the Criminalistics Institute. Notably, he called Makshakov six times throughout the night of 19 to 20 August 2020. It was during that night that the poison would have been administered on Navalny’s clothes.

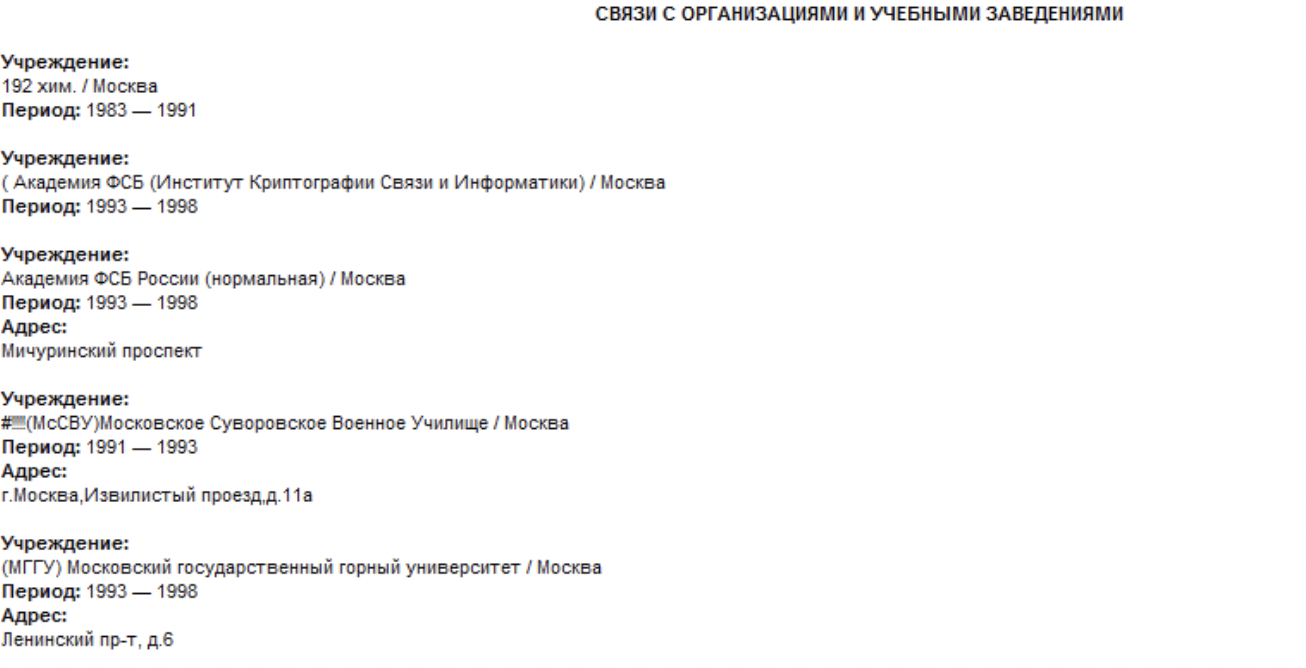

Sukhinin, born 1975, was discovered as an operative of interest for the first time during this investigation. His CV, compiled from archived (now deleted) postings on his Odnoklassniki (OK) social media profile, shows that after finishing a high-school, he studied at the Moscow Suvorov Military College and then graduated from the FSB academy, with a specialisation at the FSB’s Cryptography Institute. In the currently active version of his OK profile he replaced this educational background with the Moscow State Forestry Institute.

Due to the lack of other historical travel data or phone records it is not possible to attribute Sukhinin to either the Second Service or the Criminalistics Institute. However, his specialisation in cryptography suggests he may have been brought in during the first two tailing trips in particular for reconnaissance or technical surveillance. This would potentially be in keeping with the technical surveillance uncovered against the likes of Navalny.

New information, New Questions

While there is no direct evidence that Sukharev, Krivoshchekov and Sukhinin were involved in or planned Nemtsov’s murder, the systematic way in which he was tailed by at least two FSB operatives linked to other assassination attempts on opposition figures before he was shot dead raises a number of fresh questions. These include whether the Russian authorities were in fact considering various methods for killing Nemtsov and the FSB squad was but just one of these options that was substituted for another at the last moment.

Alternatively, if the FSB squad was involved in the planning and the assassination of Nemtsov, could they have simply positioned the now convicted Chechens near the opposition politician in the weeks and days before the murder in order to ensure plausible suspects and deflect suspicions away from them? Another logical question is whether the FSB squad that tailed Nemtsov so diligently for 10 months would have been able to miss noticing a competing Chechen tailing party within Moscow, assuming they were unaware of them.

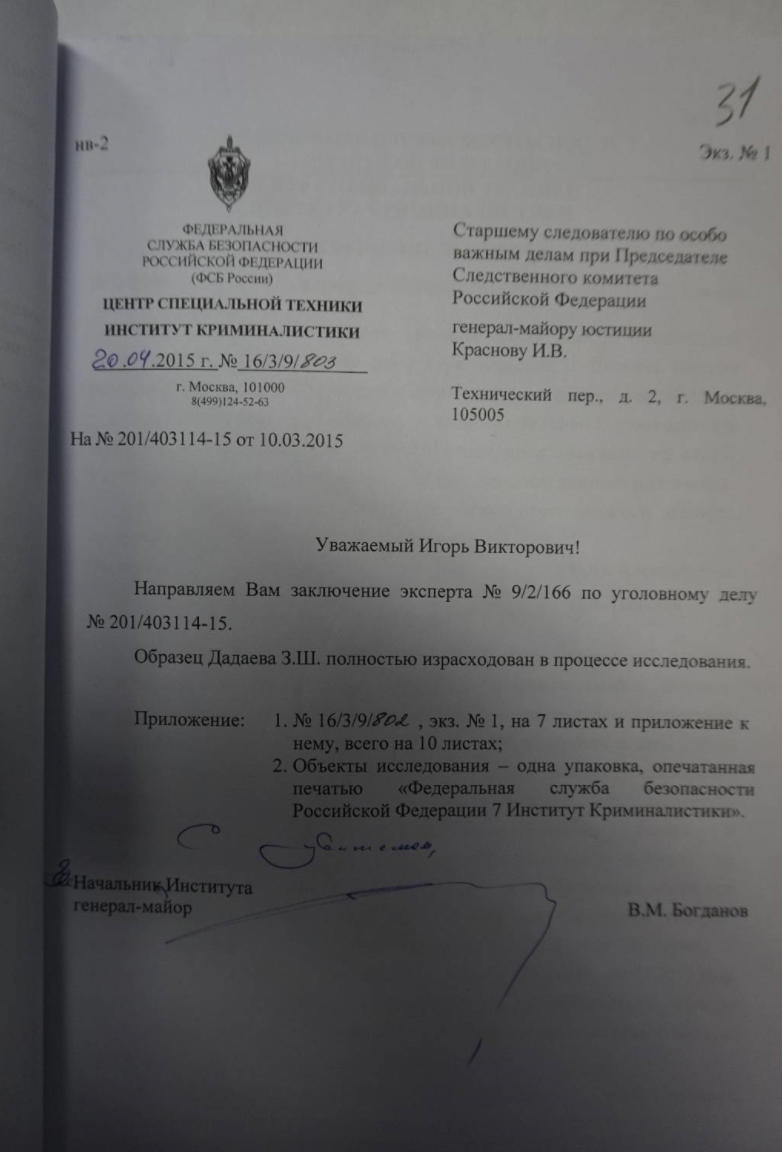

A separate set of questions are raised by the role played by the FSB Criminalistics Institute in the investigation of Boris Nemtsov’s murder. Several members of this organisation were later implicated in the poisonings, and the attempted cover-ups that followed, of other Kremlin opponents like Navalny. Yet the forensic report claiming to prove the match between Zaur Dadayev, the man convicted for Nemtsov’s murder, and DNA traces found on the crime scene was signed by the now sanctioned ex-director of the Criminalistics Institute, Gen. Vladimir Bogdanov.

Documents from Case Files (click to open)

All told, 45 out of a total of 55 forensic analyses into the murder of Boris Nemtsov were performed by the FSB’s Criminalistics Institute, court documents reviewed by Bellingcat indicate.

This would appear to mean the FSB unit directly involved in the attempted assassinations and tailing of several other opposition figures was providing a key evidential component for the trial of the most prominent and shocking political assassination in Russia’s recent history.

In response to our investigative findings, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said: “This does not have and cannot have any relationship to the Russian government. It looks like just one more false rumour.”

Attempts to reach FSB operatives Sukharev, Krivoshchekov and Sukhinin were unsuccessful and their known phone numbers appeared to have been disconnected.

This investigation was conducted by Bellingcat, The Insider and the BBC. Christo Grozev served as the primary researcher for Bellingcat, with contributions from Yordan Tsalov and Roman Dobrokhotov.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here.