Russia’s Clandestine Chemical Weapons Programme and the GRU’s Unit 29155

On October 15, 2020, the European Union imposed sanctions on six senior Russian officials and a leading Russian research institute over the alleged use of a nerve agent from the Novichok family in the poisoning of opposition leader Alexey Navalny. Russia dismissed as baseless the EU’s allegations that it had not complied with its obligations, under the convention it ratified in 1997, to discontinue its chemical weapons program. Russian officials said the country had nothing to do with Navalny’s poisoning and implied that if any party had used nerve agents on him, it would have been Western secret services. Vladimir Putin, who in 2017 had personally watched over the destruction of the last remaining Russian chemical weapons stash, ridiculed the findings of four separate laboratories, confirmed by the OPCW, that a Novichok-type organophosphate poison was identified in Alexey Navalny’s blood.

Two years earlier, in 2018, Russia had dismissed as unfounded allegations that its military intelligence had used Novichok to poison former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter. Similarly, Russia had then stated that it had no ongoing chemical weapons program and had destroyed all of its prior arsenals; while alluding that UK agencies may have used their own stash of Novichok to poison the Skripals in a false-flag operation.

A year-long investigation by Bellingcat and its investigative partners The Insider and Der Spiegel, with contributing investigations from RFE/RL, has discovered evidence that Russia continued its Novichok development program long beyond the officially announced closure date. Data shows that military scientists, who were involved with the original chemical weapons program while it was still run by the Ministry of Defense, were dispersed into several research entities which continued collaborating among one another in a clandestine, distributed R&D program. While some of these institutes were integrated with the Ministry of Defense – but camouflaged their work as research into antidotes to organophosphate poisoning – other researchers moved to civilian research institutes but may have continued working, under cover of civilian research, on the continued program.

Our investigative team believes the St. Petersburg State Institute for Experimental Military Medicine of the Ministry of Defense (“GNII VM”), likely with the assistance of researchers from the Scientific Center Signal (“SC Signal”), has since 2010 taken the lead role in the continued R&D and weaponization of the Soviet-era Novichok program.

Crucially for our conclusions, we have identified evidence showing close coordination between these two institutes and a secretive sub-unit of Military Unit 29155 of Russia’s military intelligence, the GRU. This unit has previously been linked to the poisoning attempts on Emilian Gebrev in Bulgaria in 2015 as well as Sergey and Yula Skripal in the United Kingdom in 2018. Telecoms data we obtained shows that the St. Petersurg-based institute communicated intensively with members of the assassination team during the planning stage of the Skripal mission, while also communicating – at highly correlated moments – with scientists from SC Signal.

The two research institutes also appear to collaborate with the 33rd Central Experimental Institute for Scientific Research of the Ministry of Defense, located in the town of Shikhany. This agency was originally involved in researching and testing the Russian chemical weapons program.

Furthermore, our research has established that these two institutes were in frequent communication – including during the planning state of the Skripal operation – with Russia’s Scientific Institute for Organic Chemistry and Technology (“GosNIIOHT”), the agency that was tasked with supervising the destruction of Russia’s arsenal of nerve agents and ensuring the termination of the country’s CW program.

The role of the 33rd Central Institute and the GosNIIOHT in the development of Russia’s nerve agent program was previously known, and the these two institutes were sanctioned by the European Union. However Neither GNII VM nor SC Signal have been sanctioned by European or US governments, and it appears that their work has stayed outside of the focus of Western intelligence services.

Extreme Toxicology at GNII VM

The sprawling complex of The Institute for Experimental Military Medicine outside St. Petersburg. Photo: The Insider

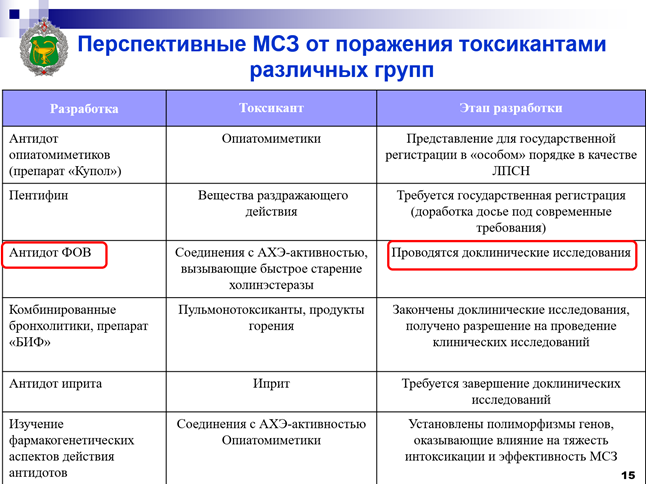

GNII VM, the Ministry of Defense’s Institute for Experimental Medicine, is a secretive military research unit located just outside St. Petersburg. There is scant public information about this establishment’s structure, personnel and projects. A succinct listing of the institute’s history and functions on the Defense Ministry’s website suggests that prior to 2015 it had existed as an adjunct research center within Russia’s Kirov Military Medical Academy, and had been focused on researching “the ergonomic properties of Russian armaments.” As of May 2015, however, the institute was given autonomy and a new focus, including “organization of scientific research in the interest of Russia’s defense and national security” and “conducting tests of the developed products.” An internal 2017 presentation of the institute, obtained by our team, shows that – at least officially – its main functions were developing and testing emergency medical equipment, medication, and treatment techniques for wartime use. In particular, the institute reported it was developing an antidote to organophosphate poisoning, with its development being – in 2017 – in a “pre-clinical trial stage”. A rare public lecture announcement from 2018 shows that leading researchers from the institute were specializing on the effects of organophosphate poisons on the human body – and were tracking the international development of antidotes to those. (Poisons from the Novichok group fall into the larger group of organophosphates – which includes also certain pesticides).

The St. Petersburg institute is headed by Sergey Chepur, a 50-year old military doctor and expert in extreme toxicology, with a special interest in the effects of organophosphate poisons on the human body. There are no open-source photographs of its director Sergey Chepur, and a rare public mention of his name is contained in a September 2020 announcement of an achievement award for his contribution to military medicine.

Sergey Chepur and Unit 29155’s

As a research entity serving the Ministry of Defense, the St. Petersburg’s institute has a legitimate and plausible interest in developing antidotes for nerve agents including organophosphates. However, telecoms data we obtained shows that key researchers from the institute are integrated with Russia’s military intelligence, including its black-operations unit (a clandestine sub-unit of GRU’s Unit 29155) to a degree that cannot be explained away by purely defensive considerations. After initially stumbling upon the phone number of the institute’s chairman, Sergey Chepur, in phone call records of Unit 29155’s commander Maj. General Andrey Averyanov, the same number kept popping up in phone records of other members of the black-ops team, including the main suspects in the poisonings in Bulgaria and the UK. This prompted us to obtain Chepur’s own phone records. They showed that he had repeated communication with at least four members of the clandestine team, and that the communications peaked just before undercover international operations undertaken by the GRU officers. Furthemore, the phone records contained metadata showing that Sergey Chepur visited the headquarters of the GRU during what appeared to be preparation meetings on the eve of the 2018 Salisbury operation.

In the period from November 2017 until early March 2018 – when the Skripal poisoning operation would have been planned by the GRU – Chepur spoke repeatedly with members of Unit 29155. He spoke or texted with the unit’s commander, Andrey Averyanov, at least 65 times (the data about these interactions were purged from Averyanov’s phone records but remained visible in Chepur’s phone metadata). In this period he also communicated repeatedly with Maj. Gen. Denis Sergeev, also known under his cover identity of “Sergey Fedotov”, who supervised both the Gebrev poisoning operation in 2015 and the 2018 Skripal poisoning. Chepur also spoke and texted many times with Alexander Mishkin (a.k.a. “Alexander Petrov”), one of the two suspects wanted by UK law enforcement over the Skripal poisonings, as well as with Col. Alexander Kovalchuk. Both Kovalchuk and Mishkin are part of the clandestine-operations GRU team and are medical doctors who graduated from the Kirov medical military academy in St. Petersburg. Alexander Kovalchuk did not travel to the United Kingdom during the Salisbury mission, but remained at the GRU headquarters during the three days of the operation which extended into the weekend.

Phone records for 2017 and 2018 show that Sergey Chepur contacted Alexander Mishkin for the first time three months before the Skripal poisoning, on the December 30, 2017. The very next day, Mishkin, traveling under the false identity of “Alexander Petrov,” took a flight from Russia to Switzerland, his travel data shows. On the day Mishkin left for Geneva, Col. Anatoly Chepiga – a.k.a “Ruslan Boshirov,” the second suspect in the Skripal poisonings – arrived back from Geneva to Moscow. During the period from Christmas 2017 until the end of February 2018, at least five members of unit 29155 traveled to Switzerland on a staggered schedule, usually with at least two undercover officers being in the country at any given time. The last member of the team departed from Geneva to Moscow on March 1, 2018, the same day on which Sergeeev, Mishkin and Chepiga bought tickets for their flight to London the next day.

Bellingcat has previously reported on the relevance of Switzerland as a frequently visited location by unit 29155 and has hypothesized that the Skripal attack may have been prepared there, or that alternatively the GRU may have expected Sergei Skripal to travel to Switzerland during the holiday period. The calls between Chepur and Mishkin in the immediate run-up to the “New Year trips” corroborate our earlier hypothesis. It is unlikely that the relatively small GRU elite team would have had the capacity to work on two separate operations in such a small stretch of time.

Immediately following Mishkin’s return from Switzerland on January 12, 2018, Sergey Chepur had several calls with Mishkin and his boss Andrey Averyanov, on January 13, 14, 17 and 18. A month before the Salisbury operation, on February 2 and 3, 2018, Chepur was contacted for the first time by Denis Sergeev. Serveev, as we previously reported, oversaw the poisoning mission from a London hotel room, where he kept continuous communication with a burner phone number in Russia. On the evening of February 12, 2018, in the course of 17 minutes (from 20:59 to 21:16), Chepur contacted three GRU officers from the clandestine unit – Mishkin, Sergeev and Kovalchuk.

On 18 January, Chepur took a one-day trip to Moscow and spent the day at the GRU headquarters. Metadata from Mishkin, Sergeev and Kovalchuk’s phone show they were at the same location at the same time. The previous day Denis Sergeev had returned from Geneva where he had spent a week.

Chepur also had a vast number of interactions with the GRU team on the February 23, 2018. In Russia, this date is celebrated as Defender of the Fatherland day and it is customary for the military to send celebratory messages to each other. However, Chepur’s communication with the GRU team members stand out from the rest as they extend late into the evening, ending with a midnight (23:59) conversation with Alexander Kovalchuk. The number of interactions and the late-night exchanges suggest they were likely linked to the planning of the Skripal operation which was to take place just a week later.

Crucially, on February 27, 2018, just three days before the GRU trio departed for London, Chepur flew to Moscow on a one-day trip. Upon arrival in Moscow, he communicated with several GRU officers as well as with members of another research institute, SC Signal. Afterwards, he headed for the headquarters of the GRU where he spent several hours. Sergeev, Mishkin and Kovalchuk were also present at the GRU headquarters at the same time.

Following his three hour stay there, Chepur made two further phone calls to a key researcher from SC Signal. Chepur then moved to the territory of 27th Military Scientific Center at Baumanskaya St. During this visit, which lasted just over an hour, he had several further calls with one of SC Signal’s lead scientists and organophosphates specialists, Victor Taranchenko.

Our hypothesis is that during this day – February 27, 2018 – final preparations for the upcoming assassination mission in Salisbury were made in Moscow, including for the delivery of the poison and the tools for its applicators, to the GRU black-ops unit.

SC Signal: From Novichok to Sports Drinks

A key part of Russia’s official chemical weapons program prior to its termination was conducted by the 33rd Central Scientific-Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense. This institute, based in the formerly closed military town Shikhany-2 near Saratov, was the R&D base for development of a particularly powerful strand of organophosphate nerve agents commonly referred to as “Novichoks.” Another military institute that had an ancillary role in the development and testing of nerve agents was the 27th Scientific Center (which was briefly incorporated into the 33rd Center); this institute oversees one of the two Russian chemical-analytical labs accredited by the OPCW.

In analyzing Sergey Chepur’s call metadata, we identified a correlation between his calls and visits with GRU’s unit 29155, and calls with several researchers who had formerly worked for the 27th Scientific Center. These included the former chairman of the center – Artur Zhirov, as well as his former colleagues Andrey Antokhin and Victor Taranchenko. Chepur spoke with Artur Jirov on 11, 18 and 30 January 2018, on one of the days – the 18 – not long after a phone call to Alexander Mishkin. However, the most notable correlation is with Chepur’s communication with Viktor Taranchenko. Taranchenko was the first person Chepur called once he landed in Moscow on February 27 and just before he headed to the GRU headquarters. Once he was at the GRU and presumably during the planning meeting for the upcoming Salisbury operation, the two exchanged several text messages.

While still working at the 27th Scientific Center, Taranchenko and his colleague Antokhin had specialized in research of cholinesterase inhibitors, a broad class to which the Novichok and other powerful nerve agents belong. Artur Zhirov, on the other hand, had specialized in research of nano-encapsulation: an innovative technique permitting the embedding of chemical compounds into a cell-like membrane-covered structure made of other compounds. This technique appeared to be a promising solution to the necessity to delay the onset of the effects of certain pharmaceuticals.

Taranchenko, like Antokhin and several other key researchers from the 27th Scientific Center, had followed their former boss in 2010 when he left the Center to become the founding CEO of a new scientific research center created through a presidential decree, the generically named Scientific Center “Signal.” SC Signal is incorporated into the structure of Russia’s Export Control Agency, and its official function is to ensure technical and scientific control over the exports of Russian materials, including “chemicals and technologies that can be used in the manufacturing of chemical weapons”

SC Signal and the St. Petersburg experimental-medicine institute work on two publicly known projects, which in theory could explain the interaction between Sergey Chepur and the Signal researchers. However, the correlation between the calls with SC Signal and members of Unit 29155, as well as a visit by Chepur to one of the addresses of SC Signal on January 31, 2018, following which he continued to the GRU headquarters, suggest that the contacts between Chepur and the SC Signal are likely linked to the planning of the Salisbury operation.

One of the labs of SC Signal is located at Natatinskaya 16 in Moscow. The same address houses one of Russia’s military institutes tasked with the destruction of Russia”s chemical weapons arsenal.

According to several experts contacted by our team, the technique of nano-encapsulation – which appears to be the area of specialization of many of the researchers working at SC Signal – may be successfully applied in the application of organophosphate nerve agents such as the Novichoks. Through this method, experts say, three effects might be achieved that would improve the efficiency and ease of application of the poison. First, nano-encapsulation could delay the onset of the poison by several hours, which may be desirable in clandestine operations. Second, it can improve the rate and speed of absorption through the target’s skin. Third, it can provide an opportunity for masking the presence of the active ingredients of Novichok, through the (overwhelming) presence in the victim’s body of chemical compounds from the cell’s “membrane” – which can be a different, decoy poisonous substance. Notably, both in the cases of the poisoning of Emilian Gebrev in 2015, and in the case of Navalny, presence of other, non-Novichok – and much less dangerous poisons – in the targets’ blood were reported.

When approached by our team to comment on the possible link between the SC Signal and the Ministry of Defense’s continued program for development of Novichok, the institute’s chairman Artur Zhirov hung up the telephone after hearing the question and without uttering a word. Reached by telephone and asked about his possible involvement in the development of organophosphate poisons, Mr. Taranchenko denied and said he was not even an expert in organophosphates – which appears to be contradicted by his body of published research.

Confronted by phone about his frequent interactions with members of GRU’s Unit 29155, Mr. Sergey Chepur said he had never spoken to any of Alexander Mishkin, Denis Sergeev, or Andrey Averyanov. He also appeared to clearly remember that he did not visit the GRU headquarters on February 27, 2018. Before hanging up, he advised us to “stop lying to everyone including to yourselves”.