The Mosul Operation: An Interim Open-source Assessment Of Conflict-related Environmental Damage

As the Mosul Operations slowly progress, a myriad of open-source information is emerging from both Ninawa province and other areas where intense fighting took place earlier indicating that the ongoing battle has left a disastrous environmental legacy on Iraq’s landscape. This could pose acute and chronic human health risks to Iraqi communities that are already struggling with the humanitarian consequences of the war. Large scale displacement, war-related trauma and lack of basic services have grave impacts on public health, and now many communities could also be affected by a polluted environment as the fighting around some of Iraq’s main oil and industrial facilities continues, combined with the scorched earth tactics employed by the so-called Islamic State (IS).

This analysis will briefly dive into some of the most vulnerable industrial sites and other potential environmental hotspots that could pose a public health threat to civilians that were targeted/damaged in the last three months or that surfaced in the course of our investigation and should be monitored. Timely identification, assessment, and verification are key to preventing further environmental damage, informing improved responses from humanitarian actors to minimize civilian exposure to toxic remnants of war, and preparing an indicative list of sources that should be part of a wider post-conflict environmental assessment undertaken by the Iraqi government with the support of relevant international expert organisations such as the United Nations Environment Program. The information discussed in the article is based on open-source information, NASA’s Landsat 8, using EOS Data Analytics LandViewer and ESA Sentinel 2, and information collected during a field visit in northern Iraq by the author end of January 2017.

When the Mosul operations began, we published a quick and dirty analysis of key industrial facilities and critical infrastructure that, if damaged or destroyed, would lead to localized pollution and affect public health. Almost three months later, more information has surfaced in the public domain that could help verify and add to the list of these potential sources of pollution.

Blue skies turn black

One of the most visible and pressing sources of pollution is the burning oil wells of Qayyarah. Over 20 wells were set ablaze in June 2016, and the fires intensified over the following months. Qayyarah, a small town of 15.000 inhabitants that sits close to an airbase, had to be partly evacuated due to fighting and the fires. Noxious smoke plumes darkened the skies over the town, and posed a serious health risk to its civilians. As UNOCHA noted in their environmental briefing [PDF]:

“The subsequent effects on local populations’ and the health of affected communities depend on the concentration of the pollutants inhaled, as well as the duration of exposure and proximity to the oil fires. Potential health effects of exposure entail skin irritation; runny nose; cough; shortness of breath; irritation of eyes, nose and throat; as well as aggravation of sinus and asthma conditions.”

Qayyarah oil field, January 2017. Image taken by author

Humanitarian organisations such as Oxfam, UNICEF, IOM and UNHCR have all highlighted concerns over the health risks of the burning oil wells.

Monitoring of the health in and around the town Qayyarah by the World Health Organisation (WHO) took off in October 2016 as medical clinics had set up near the town that began to include registration of the medical cases reported in the clinics in the WHO’s E-WARN system. Acute respiratory infections reported to the clinics did not show a steep increase in reported problems until week 46 when IS set fire to an Al-Mishraq sulphur factory, releasing 92 kilotons of sulphur dioxide that had acute effects on the local communities. The numbers of patients reporting respiratory problems had a steep increase from that week onwards. Over 20 people died to complications caused by the pollution, and over 1500 people [PDF] were seeking treatment after being exposed to the sulphur clouds spreading over the area. The situation was temporarily worsened as an attack on a water treatment facility released a cloud of chlorine gas, which is used for water purification.

According to the WHO numbers, provided to the author, there was a steep increase of 40% in reported cases of acute respiratory problems at the clinics in Ninawa governorate. However, after the fire was extinguished the reported cases went back to ‘normal’ levels, as registered in 2015. Yet, there are ongoing concerns from both humanitarian organisations and local residents that the burning wells and oil spills could pollute the drinking water, therefore it is imperative that the Iraqi government – with support of relevant organisations – put environmental monitoring systems in place, specifically for groundwater sources and soil, and start raising awareness among local communities on food security and hygiene, as prolonged intake of oil soot through food or ingestion can lead to health problems.

As the Mosul operations are ongoing, there is a continuous risk that industrial sites or critical infrastructure could be damaged, leading to the release of hazardous substances in the environment. Since the release of our previous monitoring blog, a number of new risk sites have been identified.

Oil sites west of Mosul (refinery and storage)

In early January, the commercial satellite outlet Demos Images posted an image of the burning Qayyarah oil wells, which included a huge smoke plume west of Mosul.

Our satellite #DEIMOS1 keeps monitoring #Mosul and #Qayyarah areas in #Iraq in spite of clouds. #Falsecolor #Infrared #MosulOps pic.twitter.com/ckaU4zHQLU

— DEIMOS IMAGING (@deimosimaging) January 9, 2017

At this location, there are several risk sites that could have been responsible. The main suspect would be the Kasik oil refinery – before the war started, it had the production capacity of 10.000 barrels a day. In June 2016 there were reports on Twitter that the refinery had been targeted, including photos that showed a smoke plume, though the location of the image has not been verified.

عاجل?

تنظيم داعش يحرق النفط في مصفى الكسك الان شمال غرب الموصل 40 كيلومتر.

.

.#الفلوجة_جبناها pic.twitter.com/ipqWixOklz— Qayser H (@Caiser_1700) June 27, 2016

However, the Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) reported only hitting a tactical unit that day in their strike report. There were also earlier reports from a local media source that the US had hit the refinery as well as oil tankers on 22 March 2016, though the OIR strike release report for that month only mentioned a strike near Kisik (another spelling of Kasik) on tunnels, fighting positions, and IEDs with no mention of strikes against oil infrastructure.

North east of the Kasik refinery, there are also two other points of interest, namely an oil storage facility, and a gas storage site. The former seems intact on satellite image from November 2016, whereas the latter has been partially damaged on all available images in 2017 on TerraServer.

edit: the gas facility turned out to be grain storage facility, which was targeted by the French Air Force. Thanks to @obretix

Fragment from French Air Force clip showing bombing of grain silo site

Sensitive #oil and gas facilities at risk around #Kisik #oil refinery, Ninawa province. #MosulOps pic.twitter.com/xJKx0vOU8v

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) February 21, 2017

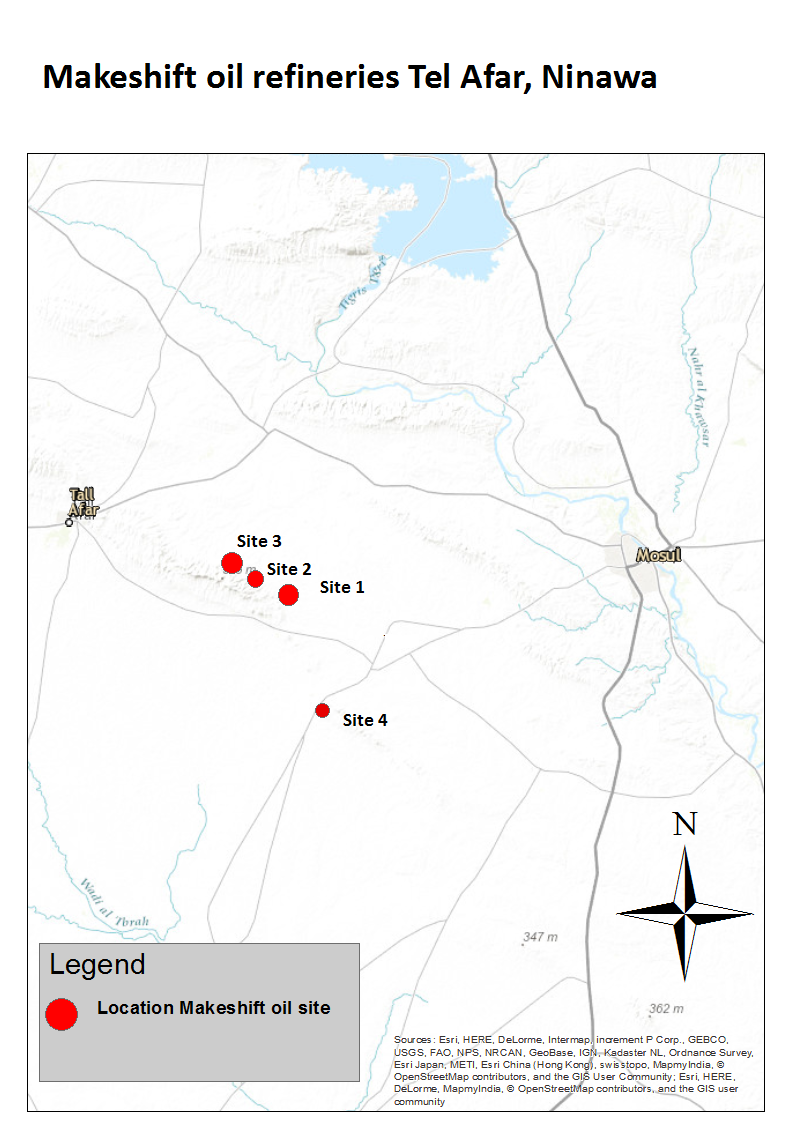

Makeshift oil refineries Tal Afar

Another potential area of concern would be the change in oil operations by IS. As professional oil refineries were hit or damaged by airstrikes, or lost due to push back (such as Baiji and Qayyarah), oil refining using makeshift structures gained more traction. Using makeshift oil refineries has become common practice in Syria’s Deir az Zor and Hasakah governorates, as indicated in previous posts here on Bellingcat and in PAX’s Scorched Earth and Charred Lives report.

In June 2016, Stratfor reported that similar artisanal production sites were also discovered in Iraq, disclosing one specific location in Ninawa, noted on the map as site 4 near the town of Adayah

These refineries likely get their crude oil from the Sheikh Ibrahim and the Addayah oil field. A recent scan of the area using TerraServer and Sentinel 2 pointed out three other locations south east of Tel Afar, with a vast amount of makeshift oil structures, in area still controlled by IS. However, little activity could be spotted at these sites.

An overview of each individual site can be seen here:

Geolocating makeshift #oil refineries in northern #Iraq. Four ISIS oil production sites near Tal-Afar. Likely operated by civilians. pic.twitter.com/AhNHi0mcoa

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) January 30, 2017

Most likely, civilians have been working at these sites to refine crude oil since at least early 2015. If civilians, including children, from local communities were working at these sites, humanitarian response and medical experts should identify if there are acute or chronic health issues in these communities.

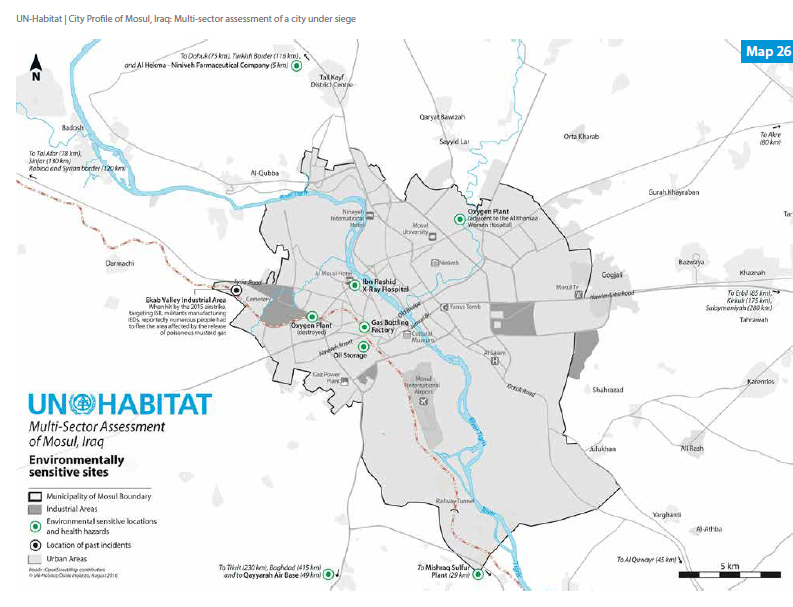

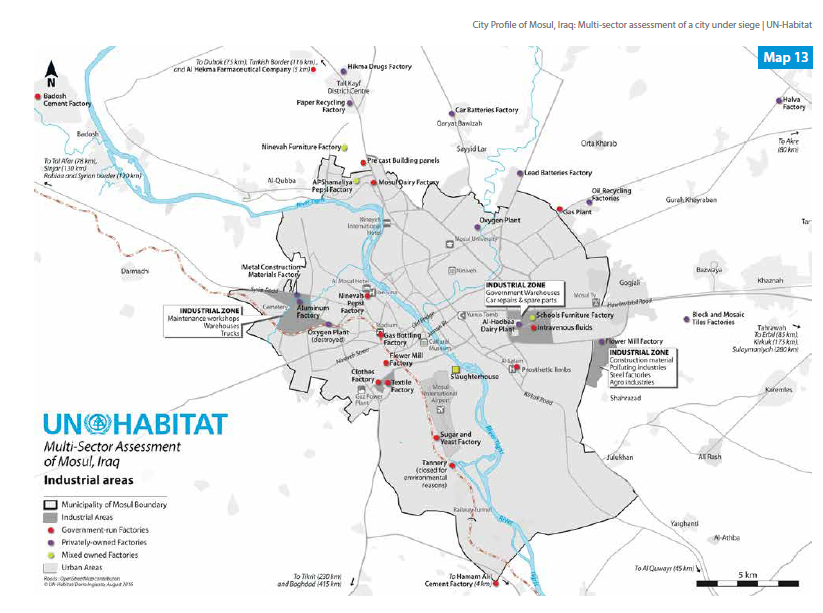

Other environmental risks from industrial facilities

Attacks on, or damage to, industrial sites could exacerbate environmental health risk for civilians and hinder humanitarian responses. Therefore, mapping potential hotspots could improve swift identification of these locations. UN-Habitat, UN’s programme focusing on human settlements, made a very informative overview of all industrial sites in Mosul in their Mosul City Profile. Information was collected both from the pre-2014 documentation of city development and economic planning from various Iraqi ministries, and from consultations with experts from Mosul who fled the city after IS had taken over. Before the war, Mosul was hosting various light and heavy industry facilities, mainly producing textiles, medical equipment, and pharmaceuticals. Most of these sites were dismantled by IS, and the equipment was either moved to Syria or sold. Some factories were bombed, such as the city’s main textile plant, and the pharmaceutical factory. UNHABITAT estimates that by August 2016, 60% to 75% of the city’s industrial and manufacturing enterprises were destroyed.

UNHABITAT Mosul City Profile Environmentally sensitive sites

At the moment of writing, it is not clear to what extent these facilities still have chemical substances in storage and could pose a health threat to communities or their environment. Therefore, expert teams deploying to visit these sites should start doing quick and dirty assessments of the presence of industrial toxins, and where needed, begin monitoring these locations. There could also be a role for citizen science in this, for example by uploading pictures of areas of concern that can be checked by an expert.

One other concern is the use of radioactive equipment in hospitals, and the potential pollution scenario when these sites are targeted. As UNHABITAT described the concerns over the Ibn Sina medical complex:

“The hospital does not have a proper waste management system. Its nuclear waste and remnants of radioactive materials are dumped unsafely in septic tanks. If bombed, there will surely be an environmental disaster. The nuclear and radioactive waste stocked in the septic tank might infiltrate into the soil and become a health hazard.”

Oil trench warfare

The latest concern to appear in satellite analysis provided by Stratfor is trenches being dug by IS south of Mosul.

Stratfor Satellite analysis of Mosul defensive positions

Though there could be various reasons for using trenches, such as blocking vehicles and troops from entering the city, or for forming a line of defence, earlier actions by IS indicate that they could potentially fill them up with crude oil and other chemical products, and set them ablaze, using them by creating a cloud cover or, in a worst-case-scenario, effectively creating clouds of poisonous gas as a last resort. Similar tactics were used in 2003 in Baghdad.

Oil trenches fire in Baghdad, 2003. Courtesy of UNEP

Burning oil well at Baiji (LandSAT)

Recent images released by NASA’s LANDSAT 8 also shows an ongoing oil fire at one of the oil wells east of Baiji oil refinery. The refinery itself was severely damaged during the prolonged fighting and bombing in 2014-2015. LANDSAT 8 data provided by EOS Data Analytics in their Landviewer archive shows the well has been burning since February 2016, however, it has likely been longer as there is no older archive imagery available.

NASA Landsat 8, January 2017

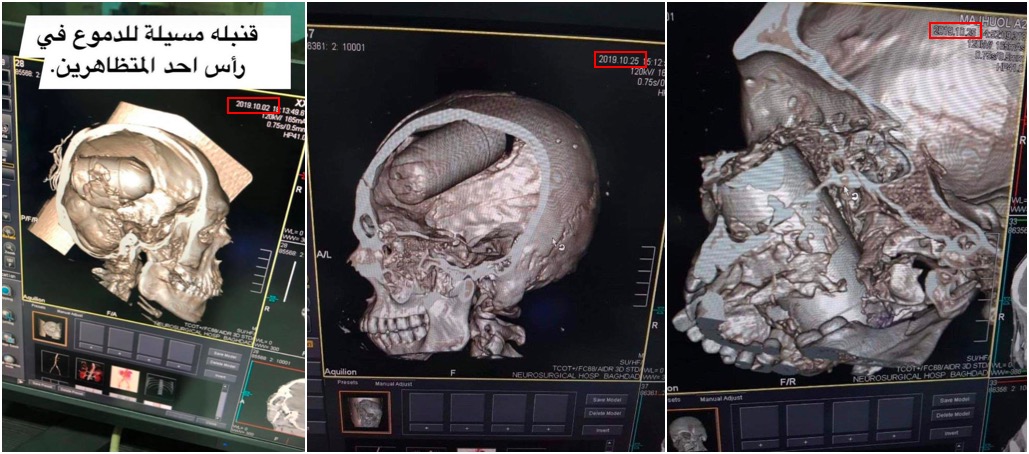

Chemical weapon risks

Various media reports mentioned IS’s attempts to produce and use chemical weapons, mustard gas in particular. Mass scale production of mustard gas grenades and missiles seem to have high priority for IS’s military leadership – in late January 2017, Russian surface-to-surface missiles were discovered next to what seemed to be a chemical warfare agent production facility. These kinds of facilities and home-made laboratories utilising industrial chemicals would pose another threat to civilians living nearby due to exposure risks. Also, r for mine-clearance staff ned to be informed as, as handling these munitions requires special equipment and expertise. Because of the chemical weapons threat, the, WHO has conducted training and capacity building activities in October 2016 for first responders on how to deal with chemical agents in case of an attack.

Need for identification and monitoring of industrial and environmental health risks

Improving response to potential environmental hotspots that could help save lives deserves more scrutiny in humanitarian action. The battle for Mosul could have direct and long-term environmental health impacts, and therefore, quick identification of potential risks would benefit a more adequate response. Combining open-source materials such as satellite imagery and social media reporting with mapping of critical areas where environmental hotspots of pollution can occur has shown to be a useful exercise in identification of potential health risks for civilians. These kinds of exercises can prove to be useful for improved humanitarian response and post-conflict reconstruction efforts. This current article has identified various key areas of concerns, namely attacks and/or damages to oil facilities, the rise of makeshift oil refineries in Ninawa province, and the heavy damage done to Mosul industrial areas.

UNHABITAT Mosul City Profile Overview Industrial Sites

With the recent liberation of east Mosul, verification of this remote collected data is imperative. The international community should provide support in terms of expertise, financial capacity, and equipment to both the Iraqi government and international organisations that operate in the field to assess if there are acute or long-term environmental health threats to residents of affected communities in and around Mosul and the wider Ninawa province. Without out, Iraqi communities are faced with potential long-term risk that adds to the already existing suffering from the direct impact of war on their lives and livelihoods.

Many thanks to Rachel Salcedo and Alex Hiniker for editing, and Christiaan Triebert for additional comments.