Friends or Foes? A Closer Look on Relations Between YPG and the Regime

This article originally appeared at Offiziere.ch

On 9th August, the high-ranking commander Major Yasser Abd ar-Rahim of Fatah Halab’s operations chamber in Aleppo gave a statement. It included some drastic messages towards the Kurdish so-called People’s Protection Units (YPG), which controls the neighborhood of Sheikh Maqsood, located in the very north of the city. Abd ar-Rahim stated that the Syrian opposition militias will take “revenge” and that the Kurds “will not find a place to bury their dead in Aleppo.” Not only does he charge the YPG of killing rebel fighters, but also of collaborating with loyalist forces during the heavy battle raging in and around Aleppo since late June.

Al-Snoubari Park (source) and Sheikh Maqsood

His claims specifically refer to incidents which occurred during the first phase of the battle of June / July 2016. When loyalist forces worked their way south on to Castello Road – by then the only route left to supply rebel held parts of Aleppo – YPG and rebels clashed several times.

On 8th July YPG made a first push towards the Youth Complex , which neighbors Castello Road. Capturing this area would have at least partly given the Kurds control over supply routes into rebel-held Eastern Aleppo. Because of Sheikh Maqsood’s elevated position (see pictures above), for years they already had a good view over the street and the traffic. Fighting between both YPG and different rebel groups continued for several days, leading the YPG to target mortar fire on the road. The Youth complex was eventually taken by the Kurdish forces on 30th July.

Taking advantage of Regime assault on #Mallah, #YPG trying to seize Youth Complex from Rebels to reach Castillo Road https://t.co/9jQvI8Ff9a

— Qalaat Al Mudiq (@QalaatAlMudiq) July 8, 2016

SAA are attempting to merge from Mallah & Layramoun at Bani Zaid, YPG in SMaqsood would act as buffer for E flank pic.twitter.com/X8GAK2rssm

— Hassan Ridha (@sayed_ridha) July 11, 2016

Liberation of the Youth Housing by YPG did not place Aleppo under siege, Castello road was not cut by YPG. pic.twitter.com/uHfVJ5ZVo3

— Dr Partizan (@Dr_Partizan) July 28, 2016

As if this fighting was not to fuel allegations of a YPG alliance with regime troops against rebel forces, at the end of July a picture emerged on Twitter. Originally posted on a pro-regime account, a group of men allegedly serving in loyalist units posed with a man wearing a YPG uniform. Already massively criticized and receiving hostile treatment for raising weapons against rebel forces, the picture, although not fully verifiable, made the situation even worse.

Very nice, #Iran #Russia #Assad #YPG hand in hand for the siege of #Aleppo (if Nubl & Zahra wasnt enough for every1) pic.twitter.com/QisBJZoFrN

— اللاذقاني (@Aswed_Flags) July 28, 2016

However, the scenery of the Aleppo battle is not the first one to produce such accusations. The earliest skirmishes are reported to have taken place in 2012, which also involved groups fighting over the control of Sheikh Maqsood in October, though regime troops were not directly at the scene.

In October of the same year all three parties were involved in the battle of Ras al-Ayn. Regime positions inside the city, located in Hasakah governorate directly on the Syrian-Turkish border, were attacked by Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters – who were soon backed by Jihadists from Jabhat an-Nusra and Ghuraba ash-Sham. They managed to drive the regime forces out, but were also involved in shootings with YPG gunmen. This was followed by a series of clashes and ceasefires which eventually resulted in the Kurds taking over the whole of Ras al-Ayn by summer 2013.

Rumors that YPG troops may have been supported by Syrian Arab Air Force (SyAAF) close air support during the battle of Tal Tamer in March 2015 are hard to analyse. However, this story seems quite unlikely, it is inconsistent and has not been referred to on a greater scale, not to mention stories of 100 Hezbollah fighters aiding YPG.

Without a doubt the biggest event to spark accusations of YPG-regime cooperation took place around late 2015 / early 2016. Firstly, a dispute erupted between several rebel groups (not all of them linked to the FSA) and the YPG about whether the latter had entered into an agreement with the regime to supply Sheikh Maqsood via loyalist-held ground. Those charges were lodged by Yasser Abd ar-Rahim among others. That very Major was already mentioned at the beginning of the text. Ironically, this all happened after the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) had been founded: a coalition of Kurdish YPG, units of former FSA affiliated groups with mostly Arab Sunni men in their ranks, Sunni tribesmen and some minor Christian militias.

In the meantime, both YPG and rebels occasionally traded fire near the isolated Canton Afrin until full action began in February 2016. On 1st February a coalition of regime troops constituting of the Syrian Arab Army (SAA), National Defence Forces (NDF), Lebanese Hezbollah, Shia Iraqi and Afghan militias, as well as Iranian troops started their attack on the besieged towns of Nubl and az-Zahraa.

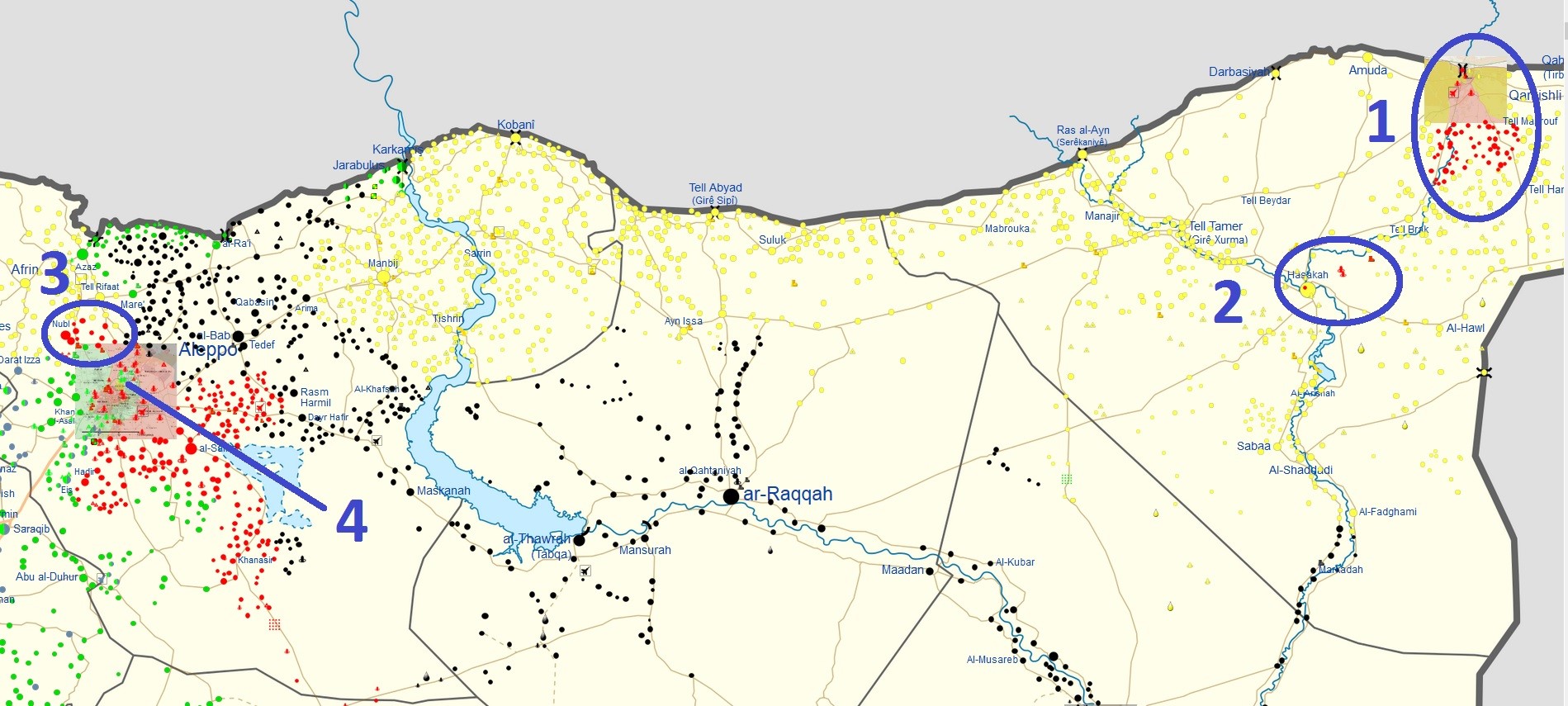

Map showing the course of the 2016 Northern Aleppo offensive. Dotted red line show government frontline before offensive, dotted orange line shows YPG frontline before offensive (Offensive began 1 February 2016; map created by MrPenguin20, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

This attack posed a real threat to the rebels, because it eventually cut the vital supply route from Turkey to Aleppo. Just as rebel forces needed as much power as possible to cope with the attackers, the SDF/YPG launched an own attack aiming eastbound, finally reaching and capturing the town of Tel Rifaat and the Menagh Air Base. This effectively cut off the rebel supply route for the second time and led to widespread criticism from western media and observers.

Amnesty International states that between February and April 2016 no fewer than 83 civilians, 30 of them being children, died in indiscriminate retaliation attacks on Sheikh Maqsood. The organization blames various groups of the Fatah Halab faction for this. Moreover, new weapons were used against the Kurdish neighborhood. For example, in April 2016 the US-backed Mountain Hawks Brigade targeted multiple SDF/YPG positions on Sheikh Maqsood’s outskirts.

Several #TOW again vs #YPG targets, but this time by Suqur Al-Jabal & for first time in #Sheikh_Maqsud (#Aleppo). pic.twitter.com/vwOVdFWnp4

— Qalaat Al Mudiq (@QalaatAlMudiq) April 7, 2016

However, the situation is a lot more complicated than one might think it is. The actions mentioned should not distract from the fact that SDF/YPG and regime forces also have a history of attacking each other.

Disputes in Aleppo date back to September 2012 when Sheikh Maqsood came under fire. Kurdish activists blamed the Syrian government and stated that this was a retaliation attack for hosting opposition members which led to the death of 21 civilians. A similar attack happened again on 26th February 2013, once more causing damage and killing civilians.

For over two years the situation remained quite calm until the SDF signed a truce with the Islamist rebel factions of Fatah Halab on 19th December 2015. Some days later, SDF and regime troops clashed on a larger scale, and Sheikh Maqsood even became the target of SyAAF attacks.

Since then, no major fighting has taken place between the two parties in the area of Aleppo city. But in fact, both sides did battle each other on other occasions, especially in the northeastern governorate Hasakah. The Assad-led government maintains exclaves in two major cities there: Hasakah city and Qamishli. Both of them repeatedly became the setting of deadly engagements of different intensity, the latest having started on 16th August 2016 , involving mainly loyalist NDF militiamen on one side and Kurdish Asayish and YPG troops on the other. After one week of fighting, the regime had to acknowledge a bitter defeat: under an agreement, all NDF inside the city were dissolved or brought to outer bases without permit to enter the city again. The only loyalist units left are police forces, which may act inside the so called security square, an area that covers no more than 5% of the city itself.

Seen as a whole, absolute assessments are impossible to be made. The Syrian battlefield should be rather seen as an accumulation of many smaller battlefields which are not necessarily linked with each other in a direct way. Two parties which are fiercely fighting each other at one scene are not unlikely to live side by side at another one. At its core, it is a way of fighting war which is characterized by a shortage of men on all sides. Battles are only fought when it seems inevitable to do. Reasons for actively starting skirmishes may vary, but often include ascertaining a certain weakness on the opponent’s side or counter some kind of provocations. Although difficult to verify, preceding clashes seemed to be sparked by events such as detention of rivals, ignoring checkpoints and fortifying one’s own positions. Rather than having the will to expel rival groups once and for all, those clashes are about setting boundaries and pointing out the limits one party is willing accept: a trial of strength.

In fact, when it comes to bringing in supplies, both sides are somewhat dependent on the other. At least since April 2016, Sheikh Maqsood has been under siege from the rebel side in Aleppo. It remains unclear to what extent goods can be smuggled into the Kurdish district through the frontline. Medicine and foodstuffs are mainly coming in through corridors linking Kurdish and regime-held areas though it’s not enough to meet the needs. Whereas rebel groups such as Fastaqim Union described that as being sign for a YPG-regime-pact, the Kurds said that these corridors were opened by Kurdish and Syrian Red Crescent.

The SDF and the Assad regime both have other main enemies: whereas the regime is mainly fighting against rebel groups of various political and religious views, trying to build a truncated Syrian state, the SDF have their eyes on connecting the three self-declared cantons in northern Syria. Both goals do not really make them get into each other’s way to a larger extent. Assad gave up governing the Kurdish areas at the beginning of the Syrian uprising, resulting in the SAA pulling out of major areas or at least not showing too much interest in recapturing areas previously lost. This is why territories held by either SDF or Assad and his allies only share four borders: Qamishli region (1), Hasakah region (2), Aleppo countryside/Canton Afrin (3), Western Aleppo city/Sheikh Maqsood (4).

Qamishli region (1), Hasakah region (2), Aleppo countryside/Canton Afrin (3), Western Aleppo city/Sheikh Maqsood (4).

Politically and even more militarily the respective situation on these four frontlines has never been the same. When there were clashes in Sheikh Maqsood, the state of affairs in Hasakah governorate usually remained quite calm and vice versa. As a matter of fact, tensions and occasional fighting between Kurdish forces and loyalist Gozarto Protection Forces in Qamishli during January 2016 happened just two weeks prior to the double cut of rebel supply lines in northern Aleppo region.

All this leads to the conclusion that in general terms there is no such thing as an SDF-regime pact. Both sides might sometimes act in a manner which benefits them both during certain operations, however, it remains unclear to what extend this is planned or arranged. Some kind of master plan Assad and the SDF/YPG stick to does not exist on a wider scale. The system both sides are perfectly skilled in is being opportunistic. Whenever it serves their goals they will keep up ceasefires and accept each other’s presence. However, if one contestant is becoming either too weak or too strong, an attack is likely to follow. Still, especially with Turkey and Russia coming closer together again, it remains unclear whether the Kurds and the Syrian regime are able and willing to uphold their respective strategies.

Special thanks to @SerioSito and @QalaatAlMudiq