Money Talks: Len Blavatnik And The Council On Foreign Relations

Last month, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), one of America’s leading think tanks, announced that it had received a substantial donation that would help round out the organization’s upcoming budget. As a statement on the CFR’s website detailed, a CFR member had graciously decided to help facilitate funding for CFR’s intern program. The donation, as CFR’s statement detailed, would provide “paid internships to over one hundred interns each year,” and would help “cultivat[e] the next generation of leaders in government, academia, and the private sector.” CFR President Richard Haass, as he wrote on Twitter, was “[g]rateful” for the “generous gift.”

It’s easy to see why CFR’s brass would express gratitude for the gift. After all, issues surrounding paying interns have circulated among any number of American institutions over the past decade, from media to civil society to, as CFR’s announcement noted, think tanks. A CFR spokesperson told Bellingcat that the donation totaled $12 million.

There was one problem, though. As CFR noted, the donation had come from the Blavatnik Family Foundation — and was specifically facilitated by CFR member Len Blavatnik.

Blavatnik may not be a household name in the United States and has not been sanctioned by any Western governments, but the involvement of Blavatnik, born in the USSR in what is now southern Ukraine, has already sparked a firestorm of internal controversy at CFR.

CFR’s willingness to accept the donation from Blavatnik’s foundation has been a case study in the “soft enabling of kleptocracy,” Sarah Chayes, one of the leading anti-corruption voices in the U.S., told Bellingcat. It also fits into Blavatnik’s previous history of working with what she described as “image launderers,” all of whom have helped Blavatnik — who has worked closely over the years with figures now sanctioned specifically by the U.S. for their role in spreading the Kremlin’s kleptocracy — in shaping the reputation of someone who accrued substantial wealth in the mad scramble for post-Soviet resource and industry.

The pushback over the previous weeks has culminated in an unprecedented protest against CFR’s move to accept and publicize the donation from Blavatnik’s foundation. One letter, addressed to Haass and signed by dozens of the most prominent anti-corruption activists in the U.S. and Ukraine, leading experts on post-Soviet kleptocracy, and former members of the Treasury Department, State Department, and National Security Council, condemned the move as a means of helping “Blavatnik [export] Russian kleptocratic practices to the West.”

Haass and CFR, however, haven’t expressed any concern about the donation, nor about the fact that the U.S.’s leading anti-kleptocracy voices have condemned the move. There’s no indication that CFR will walk back the donation, despite the unprecedented pushback they’ve received.

Neither Blavatnik nor his Blavatnik Family Foundation responded to Bellingcat’s questions. CFR spokesperson Lisa Shields told Bellingcat that CFR “reject[s] the letter in its entirety.”

There are no indications that Blavatnik or the Blavatnik Family Foundation committed any illegal acts — which is, to the signatories of the letters to CFR, part of the point behind their criticism of CFR’s willingness to so eagerly accept the donation from Blavatnik’s foundation.

“It is more than disappointing to see the Council on Foreign Relations take millions of dollars from a shady billionaire like Leonid Blavatnik, and excuse it by claiming the money will help interns,” Elise Bean, former staff director and chief counsel on the U.S. Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, told Bellingcat via email. “The CFR is helping to neutralize Mr. Blavatnik’s notoriety and extend his influence by enabling him to hitch a ride on its once sterling reputation. It is painful to see how money talks and the odor of corruption is ignored by CFR leadership when it comes to the Blavatnik millions.”

The donation, added Chayes, illustrates that “it’s frankly open season. It broadcasts to the Kremlin that if you just disguise your money a little bit, the U.S. system is still fully penetrable.”

Blavatnik’s Money: Where It Came From, Where It’s Going These Days

The substantial donation from Blavatnik, who, according to estimates by Forbes, is worth nearly $19 billion, is far from his first financial gift to a prominent Western institution. In 2010, he donated over $90 million to Oxford University to found the Blavatnik School of Government, with an additional donation of approximately $60 million to the Tate Modern, bankrolling the museum’s Blavatnik Building. In the U.S., Blavatnik’s most substantial donation went to Harvard University last year: $200 million to Harvard Medical School, founding the Blavatnik Institute. Those donations are among the reasons CFR refers to Blavatnik on its website as a “distinguished philanthropist.”

But the questions surrounding the provenance of Blavatnik’s wealth, and the business partners he’s accrued along the way, have resulted in a number of red flags thrown up over the past few years. It’s not difficult to see why the signatories to the letters calling for CFR leadership to reconsider — who, it must be noted, included a number of fellow CFR members themselves — had concerns about CFR’s public association with Blavatnik and Haass’s public praise for the donation.

To wit, the Financial Times profile on Blavatnik earlier this year listed a string of colleagues and business partners with whom Blavatnik has worked over the past few decades, some questionable, and some outright concerning. For instance, Blavatnik appeared, at least until recently, close to Viktor Vekselberg, a Russian oligarch sanctioned last year for his role in Russia’s “malign activity” in 2016 and afterward. Other former business contacts include Oleg Deripaska, another Russian oligarch and close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was also sanctioned specifically by the U.S.

Alongside Vekselberg, Blavatnik formed a company, Renova, in the early 1990s. The two began accruing assets in Russia’s aluminum industry — and, shortly thereafter, oil, with investments in an oil producer named TNK. The timing was propitious, and happened to coincide with the rise of the other gargantuan oligarchic fiefdoms that would come to dominate post-Soviet Russia. Not long thereafter, Blavatnik’s estimated wealth increased dramatically, highlighted by a 2003 partnership between TNK and British hydrocarbon giant BP, a move that made Blavatnik, along with his partners, billions of dollars. (A Financial Times profile of Blavatnik earlier this year noted that Blavatnik’s “head of press relations asks reporters to confirm that Blavatnik will not be referred to as an oligarch in any article before agreeing to arrange potential interviews. Those who do use that word are left to face complaints from his lawyers, who also protest when the fact of his Ukrainian birth is publicized without clarity about his U.S. and U.K. citizenships.”)

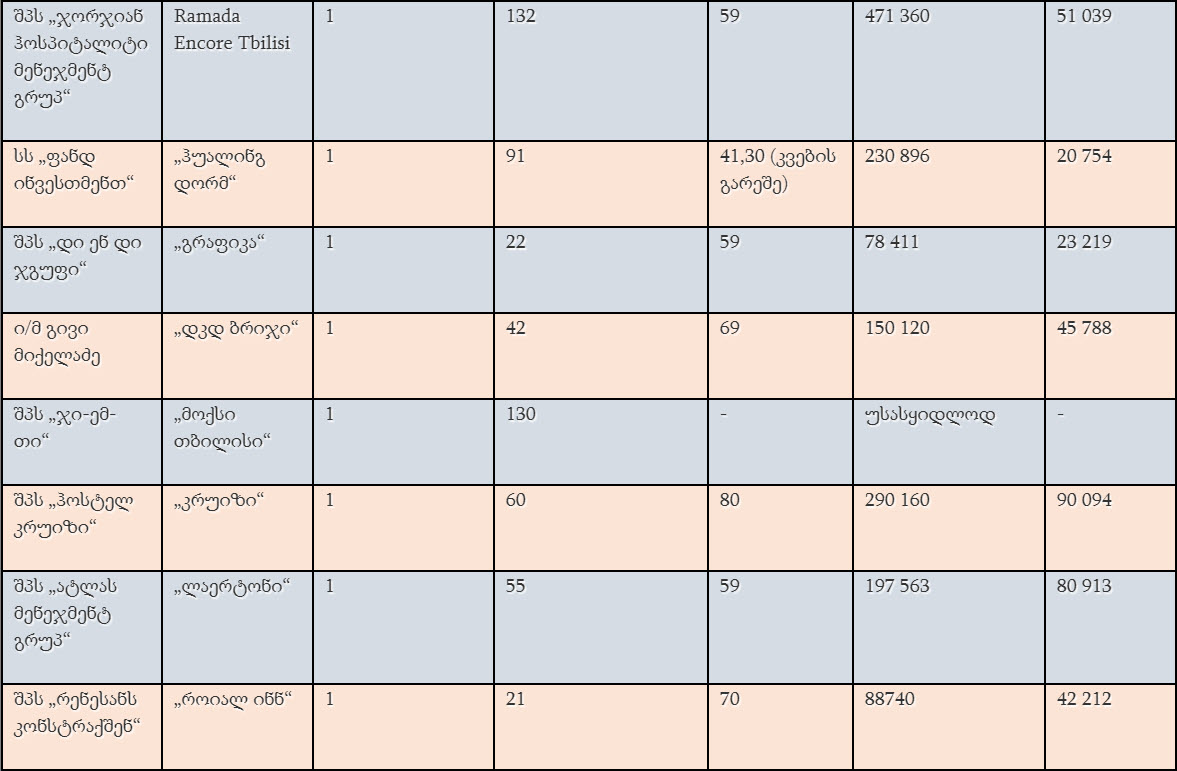

From there, Blavatnik turned west. While others like Vekselberg and Deripaska hewed close, both publicly and privately, to the Kremlin, Blavatnik began spending time picking up assets in the U.S. and Europe. The purchases were hardly subtle. In 2011, for instance, Blavatnik bought Warner Music for some $3.3 billion. This wasn’t just a foothold in a new industry for Blavatnik, but a chance to hobnob with the best and brightest in America’s music, film, and television industries. (As The Hollywood Reporter noted in a recent run-down of all of Blavatnik’s entertainment contacts, the sources of his wealth “aren’t entirely clear[.]”) Other investments included things like luxury hotels and petrochemical companies.

Donations To Democrats And Republicans

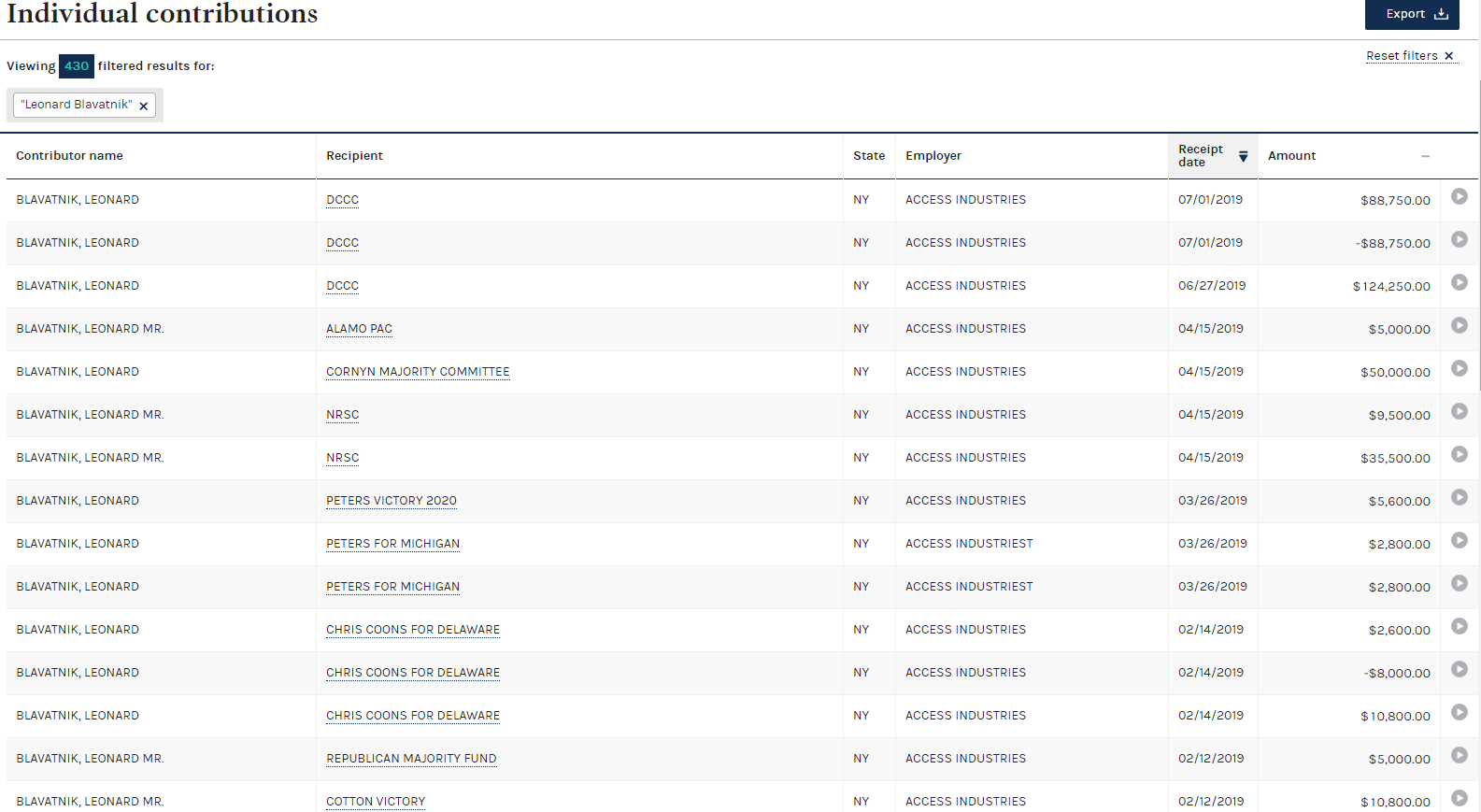

Along the way, Blavatnik kept a relatively low profile politically, and made efforts — both personal and financial in nature — to retain friends all across the political spectrum, especially in the U.S. Having gained U.S. citizenship, Blavatnik has made a concerted effort to financially back both Democratic and Republican candidates over the years. In 2016, though, Blavatnik split with his prior precedent, and poured some $6 million into Republican coffers, as well as donating $1 million directly to President Donald Trump’s inaugural committee. Over the past year, Blavatnik has returned to his old habits, and begun donating across the aisle, according to data from the Federal Election Commission.

But in the aftermath of Russia’s 2016 interference efforts, new questions began to swirl about Blavatnik’s funding. Not only did the U.S. sanction individuals like Vekselberg, figures with whom Blavatnik had previously been close, but last year it emerged that Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s office had specifically investigated Blavatnik’s donations to Trump’s inauguration. Vekselberg also told the Financial Times that he attended Trump’s inauguration at a table Blavatnik paid for, although Blavatnik’s spokesperson denied this.

Almost immediately thereafter, Blavatnik’s donations came under renewed scrutiny. It wasn’t the first time; when Oxford accepted Blavatnik’s donation, a number of prominent academics and anti-corruption voices publicly protested, saying that Oxford “should stop selling its reputation and prestige to Putin’s associates.” (Blavatnik has said that he hasn’t met Russian President Vladimir Putin since 2000.)

In December 2018, the Washington-based Hudson Institute accepted a donation from Blavatnik – and then returned the donation, following a similar outcry from anti-kleptocracy voices. (In the interest of full disclosure, this reporter is a member of the advisory council of the Kleptocracy Initiative, which is housed out of the Hudson Institute.)

A couple years after Russia’s multi-pronged election meddling efforts in the U.S., and with questions swirling around the roles and financial decisions of all those who made their wealth in post-Soviet Russia — especially around those who still haven’t fallen out of favor with the Kremlin — eyes suddenly turned askance at Blavatnik’s involvement, and Blavatnik’s designs. As Ann Marlowe wrote in the New York Times, “Mr. Blavatnik is entitled to spend his money how he pleases. But institutions like the Hudson Institute and Harvard, which at least in principle stand for the ethical pursuit of knowledge, sully themselves by accepting it.”

“Socially Unacceptable”

That precedent, though, didn’t appear to give CFR any pause. “I see specific dangers [within Blavatnik’s donation to CFR],” Ilya Zaslavskiy, an expert on corruption in Russia and head of the Underminers project, which examines how Russian oligarchs use their wealth to undermine liberal democracies, told Bellingcat. “I see [Blavatnik] and his proxies and his network now being able to enter not only other programs with CFR, but all other leading think tanks – not only in the U.S., but in the world. I see it as a general acceptance of Russian tainted money.”

“It just has to become socially unacceptable among senior economic and political” figures to accept donations like this, Sarah Chayes added.

This was the theme summed up in the formal letters sent to CFR over the past few weeks, signed by some of the most prominent voices studying, and trying to combat, modern kleptocracy.

As the initial letter, sent to Haass on September 18, read:

We are U.S., European and Russian foreign policy experts and anti-corruption activists who are deeply troubled by your announcement last week of a new $12 million CFR internship program to be named after the donor, Leonid (Len) Blavatnik. We regard this as another step in the longstanding effort of Mr. Blavatnik — who, as we explain below, has close ties to the Kremlin and its kleptocratic network — to launder his image in the West.

The letter noted that the willingness of CFR to accept the donation from Blavatnik’s foundation came as “the role of Russian networks in undermining democracy from Eastern Europe to the United States has become plain[.]” As such, the signatories, including leading anti-corruption experts and fellow CFR members like Louise Shelley, head of George Mason University’s Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center, urged CFR “to review your decision, and to apply the high standards of ethics and due diligence that an organization of CFR’s leading stature should wish to model.”

The letter also came with a raft of footnotes, citations, and examples of Blavatnik’s business dealings and relations that should have given CFR cause for concern. One section, for instance, detailed “a 2013 deal orchestrated by Russian President Vladimir Putin and Putin confidant, former deputy prime minister and now Rosneft chair Igor Sechin, Blavatnik reaped an estimated $7 billion from the sale of the oil company TNK-BP to the state-owned Rosneft conglomerate. Subsequent investigation indicates that as much as $3 billion of the total was an inexplicable overpayment by the Russian government.”

Blavatnik’s connections to any number of other Russian businessmen specifically sanctioned by the U.S. for their role in expanding the Kremlin’s kleptocracy also received mention in the letter. “Blavatnik’s connections to corrupt Putin-supported oligarchs and officials are longstanding and well known,” the letter noted. “For example, Blavatnik’s business partners include several individuals who are sanctioned by the United States government, such as Viktor Vekselberg, Oleg Deripaska (both designated by the U.S. Treasury in April 2018 under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act), and Alexander Makhonov (via Blavatnik’s media enterprise Amediateka — the Russian analogue of Netflix).”

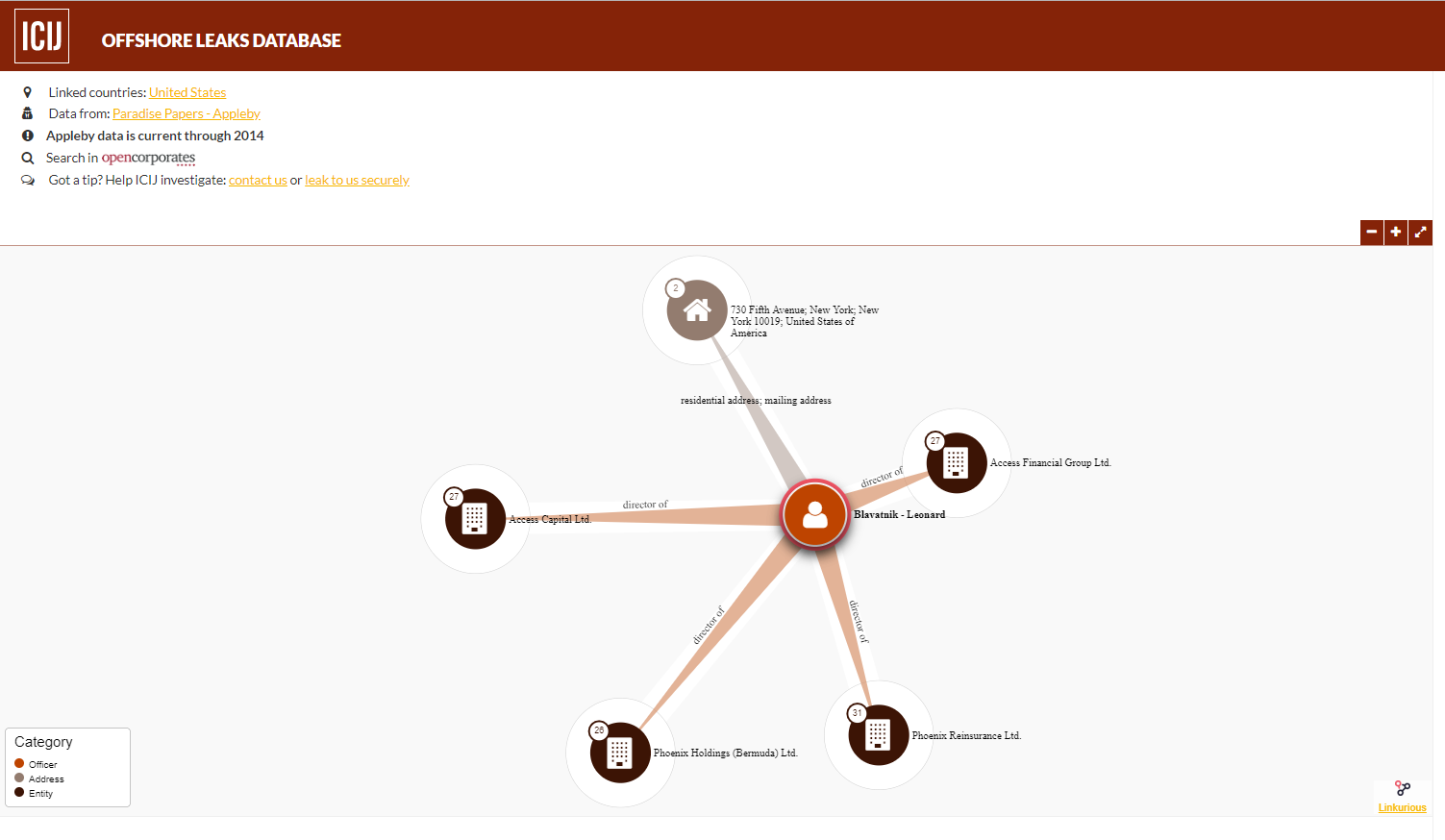

That wasn’t all. The letter further added that Blavatnik is mentioned multiple times in the 2017 Paradise Papers, including as the director of multiple entities in both Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, two of the most notorious offshore havens extant. And according to the letter, “Spanish investigators investigators recorded two Russian mobsters — Vladislav Reznik (a Duma Deputy) and Gennadiy Petrov, boss of the Tambovskaya organized crime syndicate — setting up a meeting for Blavatnik. That is a disturbing revelation for a self-proclaimed supporter of good governance, which warrants deeper examination.”

As the signatories concluded:

It is our considered view that Blavatnik uses his “philanthropy” — funds obtained by and with the consent of the Kremlin, at the expense of the state budget and the Russian people — at leading [W]estern academic and cultural institutions to advance his access to political circles. Such “philanthropic” capital enables the infiltration of the U.S. and U.K. political and economic establishments at the highest levels. It is also a means by which Blavatnik exports Russian kleptocratic practices to the West.

Haass’s response to the letter took over a week to arrive and didn’t offer any details on any due diligence CFR may have done on the provenance of Blavatnik’s wealth. Instead, he noted the “rigorous review” CFR undertakes pertaining to donations from individuals and foundations, “consistent with best practices for organizations that accept charitable contributions to make sure that acceptance of the gift poses no risk to our reputation for non-partisanship, independence, integrity, and academic freedom.” CFR, Haass noted, was “confident that this gift from the Blavatnik Family Foundation to fund the internship program here meets these criteria.” Haass also wrote that CFR apparently received a “highly positive response” from other CFR members regarding the donation, although he did not specify who these members were.

“The long-term impact of this gift is difficult to overstate,” Haass concluded.

A few days later, Haass received another note with further criticism, and further questions. “[W]e and the letter’s signatories found [Haass’s response] disappointing,” the Sept. 30 letter noted. If anything, the second letter was even more critical of CFR’s willingness to accept the donation from Blavatnik’s foundation, and to publicly praise it along the way:

Our most urgent concern is this. You speak of the long-term impact of this donation. In our view, that impact extends far beyond the potential value of the money to future interns, beyond even CFR. That impact will touch upon the health of American democracy.

Blavatnik has mounted a longstanding effort to launder his image by linking himself to precisely the type of respected institutions you mention. That is his strategy.

The second letter noted that the “fact that some CFR members may be satisfied with this contribution does not absolve you and the directors from your own stringent responsibilities to consider its ramifications.”

The letter closed with a one specific request: “Our request is simple and substantive: reverse your decision to accept Blavatnik’s $12 million. We consider this matter to be of grave importance and will continue working for a better outcome.”

This time, Haass didn’t even respond himself. Instead, Lisa Shields, a CFR spokesperson, responded. “This is to acknowledge that the Council on Foreign Relations is in receipt of your September 30 email,” Shields wrote. “We see nothing in it that in any way changes what was communicated to you in the response from CFR President Richard Haass on September 26.”

It’s unclear what the next steps in terms of internal criticism may be, and Haass has given no indication thus far that he has second-guessed his willingness to accept the money from Blavatnik’s foundation.

Zaslavskiy believes the damage is already done — and the precedent is already set.

“CFR is arguably the No. 1 or No. 2 think tank in the U.S., and essentially in the world,” he said. “It’s very close to the U.S. government… It’s really the most elite, and government-connected, place. So if that bastion falls, then it really for me entails a whole domino effect.”