How Schoolchildren Became Pawns in Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis

It was midday on 24 October last year when a group of men on motorcycles wielding machetes and firearms arrived outside Mother Francisca International Bilingual Academy in the Cameroonian town of Kumba. By the time they left, they had murdered seven children and wounded a dozen more. Several more children were injured as they saved themselves by jumping from the windows.

The Kumba Massacre made headlines around the world and caused revulsion in Cameroon, which is in the throes of an armed conflict between the central government and a separatist movement in its two Anglophone regions known as the North-West and South-West.

This event was not the first attack on a school in Cameroon, nor the last. In early February of this year, a private school was torched, reportedly by separatists, in the village of Kungi, near the town of Nkambe in the North-West. How could the government have failed to protect children in what was supposed to be a government stronghold, asked local media.

COVID-19 has taken children around the world out of school for months at a time. But in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions, schooling has been restricted for nearly four years. A separatist-enforced school boycott and a harsh government response have jeopardised children’s right to a safe education.

In this escalating crisis, kidnappings, extortion and killings of civilians have become widespread. Accusations have been levelled against separatist forces, but also against the government. For example, in February 2020 a group of Cameroonian soldiers and allied militias reportedly massacred over 20 civilians in the town of Ngarbuh, an incident for which the Cameroonian army eventually admitted some culpability. This is no easy country for reporting; Cameroon’s government itself is widely considered authoritarian, with a record of human rights violations.

But as graphic images of attacks on civilians continue to surface, open source techniques can piece together some of the story — telling how Cameroon’s schoolchildren, as well as their parents and teachers, have been caught in the crossfire of what is often described as one of the world’s most underreported conflicts.

Through analysing open source material from Cameroonian social media, Bellingcat has verified 11 further attacks against schools and children in the Anglophone regions starting in 2018 and continuing into the early months of this year. These videos, collected by the Cameroon Anglophone Crisis Database of Atrocities and the Berkeley Human Rights Center, reveal the ongoing scale of Cameroon’s humanitarian crisis, of which Kumba is only the best known example.

What is Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis?

Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis is rooted in the country’s colonial past. Cameroon, once a German colony, was dismembered by Britain and France at the end of the First World War. France took the lion’s share of the country, while the areas bordering Nigeria were administered under British colonial rule as the British Cameroons. English became their dominant language and common law was practiced in their courts. After French Cameroon gained independence in 1960, the British Cameroons were given a plebiscite to determine their future. The northern half joined Nigeria, while the southern half joined French Cameroon to become the Federal Republic of Cameroon. But the autonomy of the English-speaking territory under the federal system did not last. In 1972, Cameroonian president Ahmadou Ahidjo centralised the country’s governance, dismantling the federation, to the anger of many Anglophones who began to organise. Ahidjo’s successor, President Paul Biya, clamped down on Anglophone activism, despite adding nominal decentralisation measures to the country’s constitution in the 1990s. Anglophone movements continued to protest poor treatment and to call for self-determination. Having ascended to power in 1982, Biya is now the world’s longest ruling non-royal leader.

The latest iteration of the “Anglophone Problem” began in 2016 when Anglophone lawyers and teachers held peaceful protests against the government’s placement of Francophone judges and teachers in their regions’ courts and schools. The Cameroonian military responded by arresting protest leaders and cutting the internet. With more moderate protest leaders in jail, a separatist movement emerged whose leaders unilaterally declared the independence of the Anglophone regions as the “Republic of Ambazonia” in October 2017.

Today, a conflict rages in which the Cameroonian military battles dozens of non-state armed separatist groups, including opportunistic bandits. There is evidence of war crimes perpetrated by all sides including the state, such as torture, extrajudicial executions and the burning of villages. The UN estimates that 1.1 million of the Anglophone regions’ six million inhabitants have been internally displaced by this fighting, 60,000 of whom have fled to neighbouring Nigeria.

A School Boycott

“Dear Parents of Ambazonia, I plead with you not to send your children to school. The terrorist occupying forces are walking within our territory and shooting rampantly […] Do not send your child to school today and start crying tomorrow, you will have only yourself to blame”, declares General Efang, ‘Supreme Commander’ of the Ambazonian Defence Forces (ADF) in Cameroonian Pidgin English (hereafter referred to as Pidgin), posing with armed men in front of an Ambazonian flag. When the war is won, he adds, its children will enjoy the best education. It is not known where and when this video was taken, but it first appeared to spread on Facebook in August 2019.

The separatist commander known as General Efang gives an address at an unknown location

School boycotts, alongside enforced moratoriums on public life known as “ghost towns”, have become something of an article of faith among separatist fighters in the Anglophone regions. Teachers who continue to work in regions under separatist control risk being branded “blacklegs”, giving armed men a pretext to harass, kidnap them — or worse.

One teacher who is currently out of work told Bellingcat that they have had to walk a thin line between separatists enforcing the boycott and government troops attempting to end it.

“I’ve been out of the classroom for three, four years now. I am missing my students and they are missing me”, said the teacher, who asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

“The first problem we are facing is with the Amba Boys [separatist fighters]. Anybody who attempts to go to school, a government school, is a person in trouble. But the second [problem] are the government forces. Because when you go to areas under their control they can say ‘Oh, you’re a teacher. So you’re the ones who started this and now the rebels are killing us. And if you are not fortunate, they can allege that you are sponsoring the Amba Boys”, explained the teacher.

The boycott of state-run schools started in 2016 as a tactic by Anglophone protesters, including some teachers, to bring the Cameroonian government to the negotiating table. As it has dragged on, demands have become increasingly radical and the safety of students and teachers has deteriorated.

Elvis Arrey Ntui, the International Crisis Group’s chief researcher for Cameroon, told Bellingcat in an interview that criminal groups with no clear affiliation had also taken advantage of the situation to extort teachers.

The prominent barrister Felix Agbor Nkongho, Founder and President of the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA), co-led the first peaceful protests in 2016 that started the Anglophone Crisis.

Nkongho was arrested and imprisoned for eight months by the Cameroonian government. Since his release, he has advocated against violence and called for schools to safely reopen. Speaking from the ground, he told Bellingcat, “Perhaps at a time the school boycott was good, but a school boycott cannot run for long. And you cannot sacrifice the well-being of kids for political reasons.”

He continued: “We are perpetuating a vicious cycle of poverty, of under-privilegedness in such a way that the kids who cannot afford an education because their parents couldn’t afford an education, they’ll end up being the lowest of society.”

For its part, the Cameroonian government has launched an aggressive drive to restart education, proposing military convoys for students and teachers to schools in the war-torn regions. The government is a signatory to the Safe Schools Declaration which restricts the use of schools for military purposes during conflict situations. However, it has been accused of using a school in another conflict zone in the country’s the Far North region as a torture site for detainees, even while students were present.

Separatist figures believe that the boycott is a logical tactic which offers leverage over the government. If the situation in the Anglophone regions returns to normality, they say, then there will be no impetus for the government to negotiate with them. This is a strategy that was detailed to Bellingcat by Ebenezer Akwanga, leader of the Southern Cameroons Defence Forces (SOCADEF) separatist group.

“I want a blanket boycott. Because I think if there is a meaningful blanket boycott — not attacking schools, not burning down schools — but a blanket boycott where every school is actually shut down from private to government institutions, it will compel the state to come to the table as soon as possible,” Akwanga said.

Cho Ayaba — the leader of another of the main separatist political bodies, the Ambazonia Governing Council as well as its military wing the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF) — told Bellingcat that children could go to school, but only if it was in territory under their control and under a separatist-approved curriculum.

“We are defending independence, and I don’t think you would want a foreign curriculum of education to be imposed within your country. The enemy must withdraw from our country […] and let us set up our own institutions to oversee the educational system”, Ayaba said.

Dabney Yerima is acting Vice President of the self-declared Interim Government of Ambazonia. “We have been consistent and have publicly observed that only parents can determine if the conditions are conducive and safe for their children to return to school”, he explained in an emailed statement. “The Interim Government wants children to study in a calm and peaceful environment and, therefore, supports community schools as a provisional measure all over the state of Ambazonia.”

The Cameroonian government did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the challenges facing education in the country’s Anglophone regions. After four years of the school boycott, UNICEF estimated in recent statements that one million children in Cameroon, including in the Anglophone regions, now urgently require protection from violence.

Panic in Limbe

The psychological impact and the fear generated by attacks on schools has increased since the beginning of the Anglophone conflict.

At the start of the 2020 school year, there was some hope that schools might finally resume. “Initially parents were not afraid and sent their children to school. [Many thought] ‘let us just see what will happen’”, another teacher from the Anglophone regions told Bellingcat on condition of anonymity. “But it did happen; the first breakdown came when children were killed at a certain school in Kumba.”

On October 27, 2020 a few days after these events, videos of mass panic began to circulate on Cameroonian social media and resonated far beyond Kumba. Bellingcat geolocated eight videos from that day to three different locations within Limbe, a coastal town 94 kilometres south of Kumba, and one location in the city of Buea. All videos appear to show children fleeing schools, afraid for their safety. Contextual information, including commentary and user comments, suggests they were in response to the Kumba massacre.

The narrator of one of the videos says, “it seems as if a school has been attacked, the primary school of Bota” and “an alleged attack, we cannot confirm it from our position”.

This particular video was shot near Bota, a suburb of Limbe, next to the football stadium and the Bota Government School.

This school is easy to find on OpenStreetMap.

We were also able to geolocate similar videos showing panicking children and parents outside the Government Practising School at a location known as Mile 1 (4.024196, 9.210055), in front of the Government High School (4.036806, 9.204917), and two videos (1, 2) showing frightened children running away from the direction of the school (4.017865, 9.208934). Finally, one further video shows children in school uniform running through foliage away from the GTHS (Government Technical High School) Molyko in Buea (4.156622, 9.278865), one of the largest cities in the Anglophone regions.

Such panic, as visible in the videos, is understandable given events we have been able to document using open source tools.

Schools Ablaze

Images visible on satellite mapping services detail the charred remains of buildings in several Cameroonian villages.

Closer analysis of these platforms proved key in verifying seven videos of school burnings which have surfaced on Cameroonian social media. Although users who upload these videos regularly blame separatist groups for the attacks, we cannot conclusively confirm the identity of individual perpetrators or their affiliations.

Four of these videos do not show the perpetrators. One shows masked men in civilian clothes, while another shows men in the uniforms of a professional military resembling those worn by the Cameroonian armed forces, as previously noted by the Berkeley Human Rights Center.

The video showing men in civilian clothing was filmed just a few weeks after the attack at Kumba. This arson attack occurred on November 4, 2020 at the Kulu Memorial College, near the main road between Limbe and the town of Moliwe (4.045870, 9.217020). The video shows unidentified men storming the school, forcing children and teachers to strip naked and then flee. Once the students and staff had vacated the building, the attackers set it alight.

Another video of the same event, uploaded to social media on November 4, shows an empty school building, the children’s clothes still on the floor, as uniformed men arrive and assess the damage. We were unable to estimate how much time had passed between the two videos because it was cloudy and therefore no shadows were visible, as is often the case in this rainy and humid part of Cameroon.

In the case of one reported incident in the town of Bafut, no video or imagery was available. Instead, social media posts claimed that during a large-scale military operation in August 2020, the Cameroonian military surrounded Bafut Palace, a UNESCO world heritage site, and burnt a state primary school (6.087581, 10.114967). Bellingcat sought to contact the Cameroonian government and military to ask about these claims but did not receive a response before publication.

Yet a comparison of Google Earth satellite imagery of the area provided visual evidence consistent with substantial damage to the school building, shown in the red square, some time between February 2018 and October 2020.

In addition to the Google images shown above, Planet.com low-resolution satellite imagery suggests that the damage to the building was inflicted between August 5 and August 11, 2020. It’s faint, but just about visible as an L-shaped building in the very centre of the image below:

At the beginning of 2021, there were a series of school burnings in rural areas across the two Anglophone regions.

On January 22, the boys’ dormitories at a Presbyterian secondary school in Mankon (5.943825, 10.144972), outside the town of Bamenda in the North-West region, were attacked. The following day, girls’ dormitories were also set ablaze. Both burnings happened at night and caused no casualties.

Both dormitories are marked with green squares in the satellite image below:

Simon Emile Mooh, the Senior Division Officer (SDO) for the Mezam Division, suspected collusion with separatists and told local media that the authorities had a “list of suspected students who are probably sympathising with terrorists.”

However, according to a local blog, nobody claimed responsibility. The same blog published high quality images [1, 2] of the aftermath, showing the charred girls’ dormitory building. We can confirm the date and location of the attack on both dormitories using Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope imagery.

Once again, these images are low resolution, but a small difference is discernible. Focus on the long buildings inside the bounded oval area in the centre of the image.

When comparing imagery from January 22 and January 23 we can also see traces of the destruction of the girls’ dormitory.

Here is a comparison between January 23 and 24:

The GIF below shows the destruction of both dormitories. A Sentinel-2 image from January 21 shows the campus before the attack. Another on January 26 shows the aftermath of the attack, and another from January 31 shows that the two dormitories had been repaired, reportedly with materials provided by Agho Oliver Bamenju, the member of parliament for Mezam North, near Bafut.

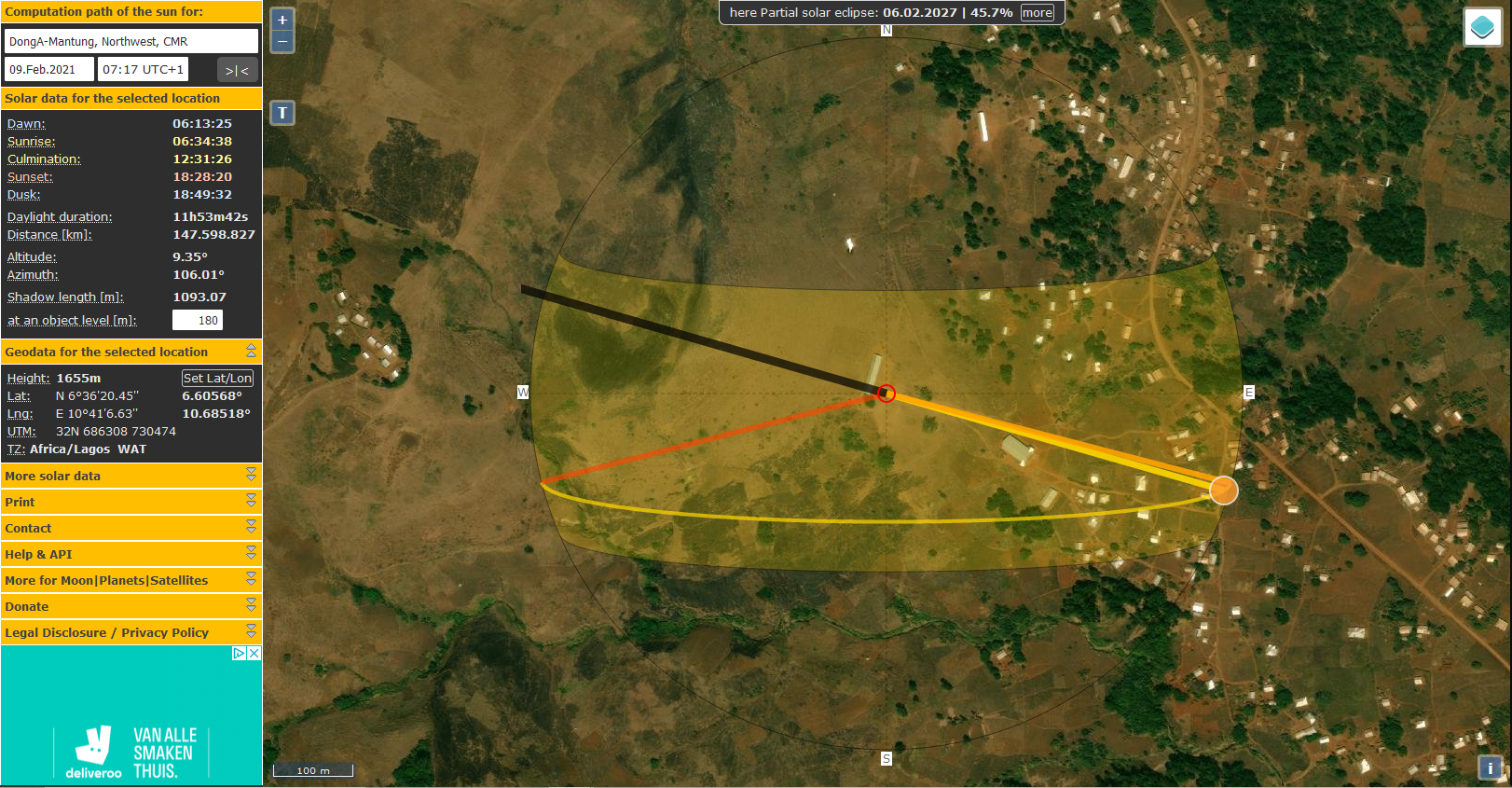

The village of Kungi in the Nkambe Subdivision lies five hours’ drive North-East of Bamenda (6.605764, 10.685076). On February 9 a Catholic school was burnt down there. The incident happened in the early morning hours before pupils and parents began to arrive.

The school is visible in satellite imagery from February 5, but by February 10 it appears to have been destroyed. According to Mimi Mefo Info, an online news network founded by a Cameroonian journalist which focuses on the Anglophone Regions, the village is considered a government stronghold.

Footage from that day posted on Facebook shows villagers at the school after it had been burnt down, appearing to assess the damage. In two videos [1, 2] which capture the same moment we see a man who, judging by his uniform, appears to be the district officer (DO) for Nkambe. According to translation from Pidgin provided by CHRDA, he scolds locals whom he had selected from the crowd, claiming that they harbour “Amba Boys” and insinuating some locals may have sold petrol to the attackers. Soldiers patrol the area.

Due to the low video quality we cannot clearly see the officer’s face, but an online Cameroonian government decree names the DO for the area as Ngidah Lawrence Che. This man’s personal Facebook account also confirms his position.

Furthermore, the position of the shadows seems to indicate that this gathering took place in the early morning of February 9.

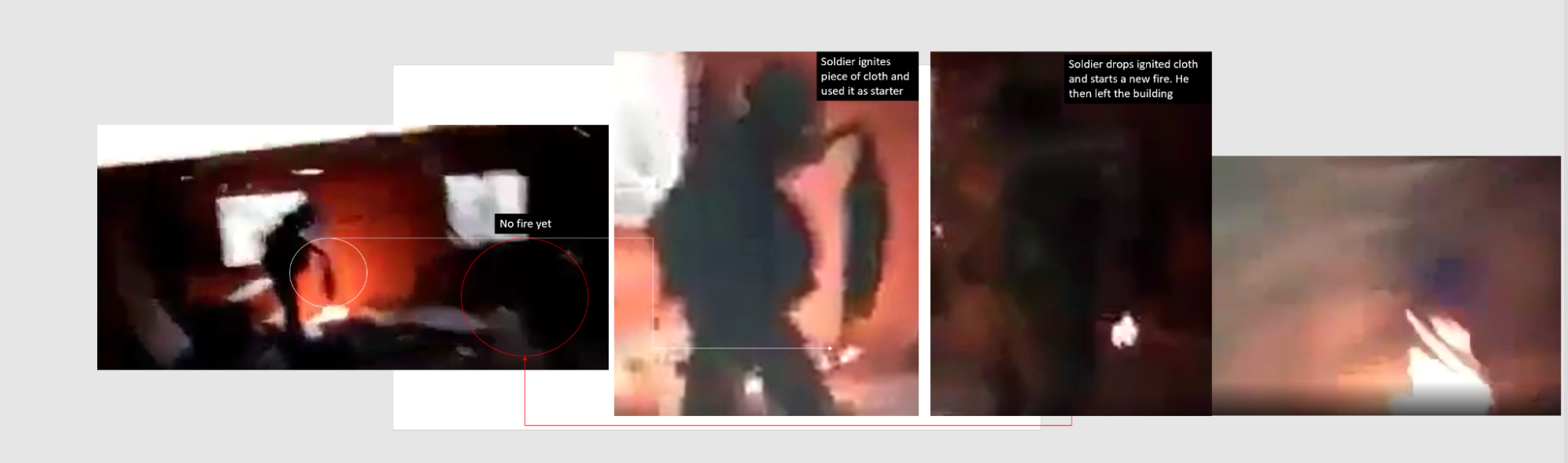

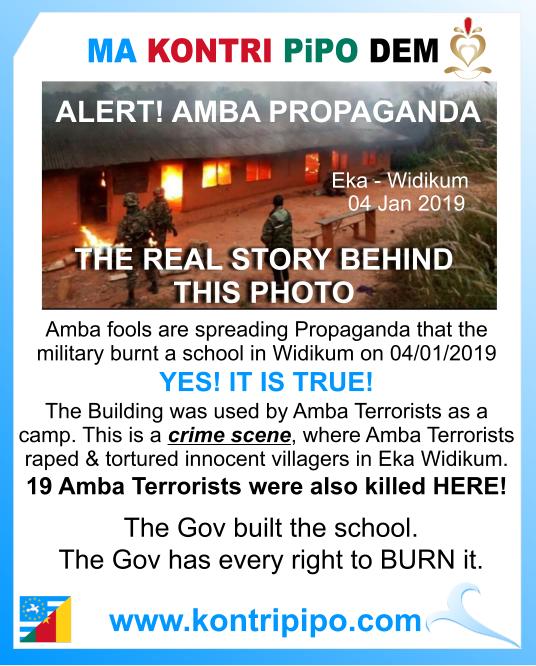

Although Cameroon’s separatist groups have by their own admission a tactical and ideological opposition to government-run schools, potential state involvement in one incident analysed by Bellingcat cannot be ruled out. A video from January 3, 2019 shows men in Cameroonian military uniforms present at the scene of a fire at a school building in a small village called Eka, near the town of Widikum (5.926791, 9.742550).

The school itself was geolocated by volunteers of the UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center (PDF file); their location findings have been confirmed by Bellingcat researchers.

The grainy video shows a group of armed, uniformed men securing the perimeter of a school building. A school desk stands on the ground outside, as does a pile of wood and an axe. The video does not show who started the fire, which is already underway when the video starts. However, the men present do not appear to be making a concerted effort to stop it. One armed man appears to be burning a piece of fabric. The fire intensifies once the camera pans back to show the building in full shot towards the end of the video.

The camouflage patterns of all the armed mens’ uniforms matches the “lizard” pattern worn by the Cameroonian armed forces. At least two of the men appear to be wielding Zastava M-21 rifles, which are also used by the Cameroonian military.

Comparison of the camouflage patterns seen in the Eka school burning video with those worn by servicemen of the Cameroonian military

A still from this video surfaced in posts the same day and the day after by Ma Kontri Pipo Dem (whose name roughly translates as “My Fellow Compatriots” from Pidgin), a highly partisan website which supports the government’s campaign against Ambazonian separatists. The website claims that the Cameroonian army burnt the school because separatist fighters had used it as a base, noting “the gov built the school, the gov has every right to BURN it.” It was not possible to ascertain whether this reporting was accurate.

Two Kidnappings in Nkwen

Students and teachers across the conflict zone have also been kidnapped and abducted by a variety of armed groups.

One of the most infamous examples of this trend, with approximately 78 children and one teacher abducted, occurred during the early morning of November 5, 2018 at a school in Nkwen (5.996305, 10.160397), near the North-West city of Bamenda.

Only later did it emerge that a group of 11 students had been abducted from the same school on October 31 and were released after a ransom was paid, according to a circular from the Presbyterian Church of Cameroon.

After the second, larger kidnapping was reported, a video began to circulate on social media, showing a group of approximately 11 children being questioned by their captors. In the video, the children give their names and the names of their parents to the person behind the camera, each stating that they have been captured “by the Ambas” and that they don’t know where they are. The children repeat near identical statements, indicating that they had likely been coerced. The fact that there are a smaller number of children in this video suggests it was of the initial kidnapping on 31 October.

The second video of children kidnapped from Nkwen shows a very large group of pupils in a dark room. Some of them wear the school uniforms of PSS Mankon, another Presbyterian secondary school in the area. One theory voiced on social media was that these pupils had been transferred to the comparatively quiet school at Nkwen for their own safety before being kidnapped. Given the larger number of students, it appears evident that this video is of the second, larger incident.

All 79 students of the Presbyterian secondary school were eventually released without ransom on November 7, though the principal and staff of the school were held for five more days. On the day after the release, parents gathered outside the gates of PSS Nkwen to be reunited with their children. One man gave an interview to local news network WAKA Africa, expressing frustration at the delays he had encountered in meeting his child. The children were released at a Presbyterian Church in the locality of Nsem, Bafut, around 16 kilometres away from PSS Nkwen.

To this day, no group has taken responsibility for the kidnapping of children from PSS Nkwen.

Some separatist groups allege that the incident was staged by the Cameroonian government to discredit separatist groups, though the government strongly denies this. In May 2020, the government claimed that one of the individuals alleged to be behind the kidnapping, ‘General Alhaji’, had been killed in a military operation.

A Teacher’s Predicament

Teachers are at particular risk of abduction. The two teachers interviewed by Bellingcat spoke of an atmosphere of fear among educators in the two Anglophone regions.

“You don’t know what will happen. The safest thing is not to be there. Being a common teacher, you can be taken by anybody. Anybody can pick you up; there will be no questions… When you’re picked up, the government will be silent. The people will be silent, because they’re afraid of what might come next for them. That’s how you’ll suffer and might even die”, said one teacher who has fled the Anglophone regions.

One video which went viral on Cameroonian social media in summer 2020 reveals what can become of teachers who are abducted. A man in an undershirt looks at the ground as he is interrogated by separatists in Pidgin. The precise location and date the video was taken are unknown.

The camera looks at a folder of documents in the man’s hands; it transpires that the captive was on his way to a school in Bamenda to supervise an information technology exam. He protests that he is not going to teach, but to earn money. Two of his brothers are fighting for the Ambazonian struggle, he pleads — a claim which invites the interrogator to contrast their heroism with his.

The teacher is told that he will pay with his blood. According to CHRDA, the teacher in question was released and is still alive. However, Bellingcat was unable to independently verify this information.

Back to School?

Schoolchildren also feature in multiple videos from Cameroon’s conflict. For the Cameroonian government, getting children back to school would symbolise victory in the conflict and success for their aforementioned back to school campaign.

For the non-state armed groups, children obeying the boycott or attending schools outside the government’s control demonstrates their hold of power in local communities.

For example Ngidah Che Lawrence, the Nkambe DO who scolded the inhabitants of Kungi after the school burning, shared a short video on his Twitter account on March 4, 2020. It shows a group of infants marching and holding a national flag. “How beautiful it feels to see these little angels in uniform”, he wrote.

This scene was geolocated to the major road in Nkambe, between a Total petrol station and a grandstand used for public events. National holidays have been celebrated on this spot with public parades, as seen in videos of Unity Day in 2019 and Youth Day in 2020 posted on Facebook by Ngala Gerard, a member of parliament for the area.

Yet marching schoolchildren have also started to feature in public celebrations put on by separatist groups.

One popular video uploaded to Facebook showed part of an Ambazonia ‘independence day’ march in October 2020. A group of children holding Ambazonian flags chant “Amba-, amba-, Ambazonia!” and are led by female school teachers. The voice of a man recording praises Ambazonia’s “community schools” as the children pass a makeshift podium.

Rural Cameroon has scant digital footprints and mapping services are often inaccurate. But on closer inspection, the video includes several clues as to the location: firstly, several of the female teachers wear hijabs, suggesting the North-West region which has a significant Muslim minority. A billboard held by the students indicates that they have come from a nearby town named Yelum, also spelt Elom. Finally, the voice of the man filming gives the location as the Bui Subdivision, then under the control of a separatist commander known as General Hassan. This separatist commander was reportedly killed in battle in February 2021.

A satellite search of Yelum yielded no matches. But a Facebook search for General Hassan revealed another video from the same location, which pans out and offers further clues — it is a football field with two low buildings with a distinctive tree in front of them.

One football field in a rural area between Elom and the town of Kumbo matched the video; a distinctive mountain in the background also matched a PeakVisor search. Digital maps of Cameroon referred to this location interchangeably as Mbiim and Mbam. Coordinates for this same settlement were discovered in an official list of villages in Cameroon, in which it is named as Mbam-Song (6.308189, 10.630388).

According to Mimi Mefo Info, since 2020 rifts have opened between separatists over school resumption. Indeed, some separatist actors appear eager to present themselves as supporters of education — albeit an Ambazonian system.

We found the following footage posted to YouTube in August 2018 showing children, many of them infants, standing in front of the Ambazonia flag while singing pro-separatist songs. Towards the end of the video a man identifies himself as “Commander Tiger” from Ambazonia Defence Force in the town of Batibo.

In September 2018, a video circulating on social media showed a “community school” allegedly run by the Ambazonia Defence Force in the same town. The narrator who introduced the school once again identified himself as “Commander Tiger”.

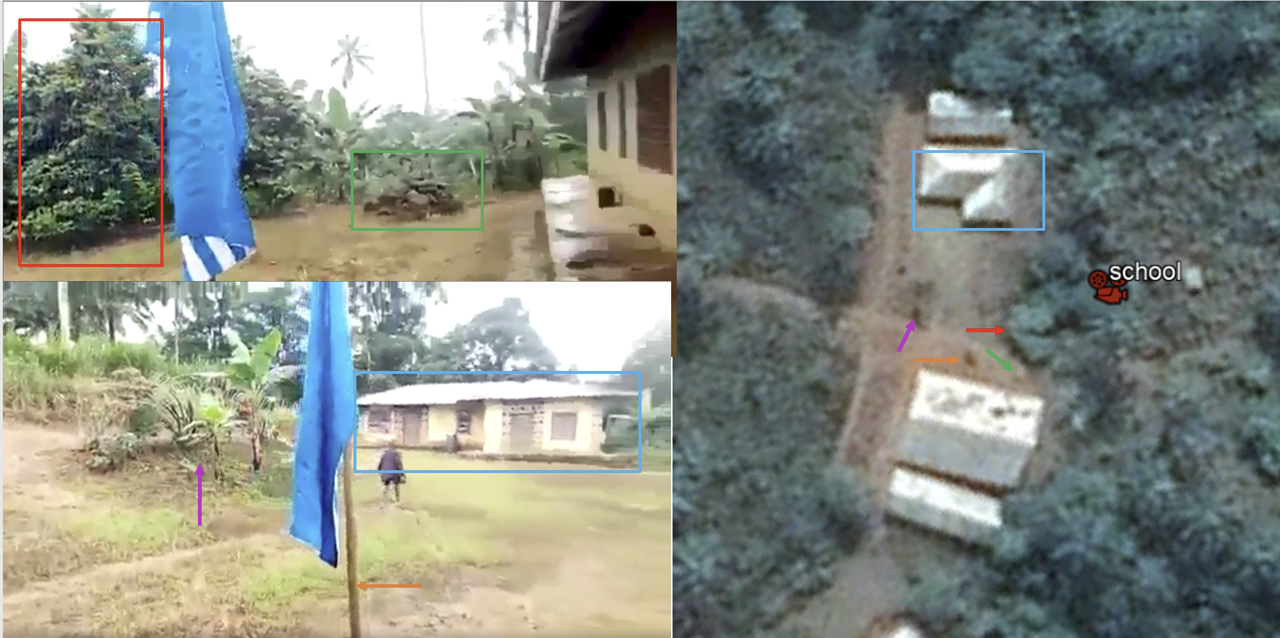

First, we verified that the videos featuring Commander Tiger were indeed filmed around Batibo.

For example, in late August 2018, Commander Tiger was seen wearing a mask and armed while entering the area close to Guzang Market in Batibo. He addressed a large cheering crowd on the occasion and sang the Ambazonian anthem with his armed group.

The same month, Commander Tiger and his group were seen blocking the main highway and threatening to burn cars at the level of a junction to a road leading to Guzang.

These videos, among others, indicated that Commander Tiger’s operations were taking place outside Batibo Central Town.

A new piece of footage emerged on November 12, 2018. This time, Commander Tiger is seen wearing his mask and accompanied by armed men. The group displays computers in front of a building which turned out to be the same school from the video which circulated in September.

In the same video roosters can be heard in the audio background and the sunlight strikes the building at a low angle which could be indicative of early hours in the morning. According to solar data and assuming the video was indeed recorded in early November in Batibo, the sun should have struck the school unit from the southeast, allowing us to confirm the precise location of the school (5.851561, 9.885138).

Commander Tiger’s video of lessons inside this school building does not provide detailed information about separatists’ groups vision for education in the Anglophone Regions. In recent years, some Ambazonian groups have claimed to be working on alternative curricula.

However, it is not possible at a distance to verify how far these plans have been implemented on the ground, or implemented at all.

Class, Gender and an Education Crisis

Women’s groups in Cameroon have been particularly vocal in calling for a stop to attacks on schools and have begged warring parties to put an end to violence.

Esther Omam Njomo is a highly prominent Cameroonian activist, humanitarian and executive director of Reach Out Cameroon, a Buea-based NGO focused on the rights of women and children. In May 2018, she initiated the South West and North West Women’s Task Force (SNWOT) which brings together women’s civil society organisations to push for peace in the Anglophone regions. In May 2019, she testified on the crisis at the UN Security Council. Upon her return to Cameroon, she faced chilling attacks. Despite her advocacy attracting numerous threats, she continues to push for peace in the conflict zone.

In an interview with Bellingcat, Njomo spoke of an emerging rift between urban communities where schools, particularly private schools, have reopened and those in more rural areas which are still unsafe. Across the regions, she explained, the poor cannot pay to send their children to school elsewhere. “You have the rich and then you have the middle class and the poor and the villages who do not have the means to send the children to school.”

This widening class divide is accompanied by deepening gender inequality, noted the prominent activist.

“A significant number of people working in Cameroon’s schools depend on their salary from the government and most of them are women. In conservative parts of Cameroon, it’s one of the only jobs open to women. But we know that teachers in this country are one of the main targets”, she added. “Just as children are suffering, so are women. Some have resorted to becoming farmers so they can feed their families.”

“What is the crime of the children who have been denied access to education? What did they do for them to be subjected to the whims and caprices of all those who started this war?”, Njomo exclaimed, stressing that she did not want to point fingers as a humanitarian and aimed to maintain an impartial stance.

The Blame Game

With attacks on schools, teachers, and students ongoing, the fear of violence surrounding education runs high. A December 2019 estimate from the Global Education Cluster found that 83 percent of schools in the Anglophone regions were closed.

“Actually restoring the system to the levels of schooling they had before the crisis is going to take a lot more time. Some of the areas are insecure and have been abandoned for three, four, five years. And it’s difficult without massive investment to get schools there going again”, remarked Arrey Elvis Ntui, the International Crisis Group expert on Cameroon.

In comments to Bellingcat, separatist leaders speaking from the diaspora where they reside, largely denied claims that separatist forces have attacked schools. They also stressed that not only had criminal elements taken advantage of the lawlessness to harass civilians — but it has allowed the Cameroonian government to portray the separatist movement as bandits who oppose schooling to the international community.

“They are fully aware that no matter what they do, the end result is that separatists will be accused because they did not call for a boycott. So when any incident occurs which affects a school, the first suspicion would be that it’s an Ambazonian group”, said Akwanga.

However, on justifying the boycott, Cho Ayaba said: “We know basically that there would be a lapse. This generation is paying the price for the next generation to have a better future. That’s what has happened in every country that has fought for their freedom”.

The separatist sources quoted in this article attributed the Kumba massacre, Nkambe school burning and kidnapping of students from PSS Nkwen to the Cameroonian government. This version of events stands in stark contrast to the position of the Cameroonian government, which has previously blamed separatists for what happened in Nkwen, Kumba and Nkambe.

Cameroon’s Ministry of Communication did not respond to emailed requests for comment before publication; neither did a spokesman for the military nor the country’s embassies in the Netherlands, France, Great Britain and the USA. Reporters contacted Cameroon’s Minister of Secondary Education shortly before publication, though she declined to provide a prompt response.

With no end to the conflict in sight, a safe and full school resumption may prove elusive. Until it comes to pass, the social and economic outlook for the next generation of Anglophone Cameroonians remains uncertain.

But as the warring parties play the blame game, children pay the price. As Esther Omam Njomo asks, “The children are our tomorrow. What tomorrow are we building with uneducated children?”

Research by Youri van der Weide, Charlotte Godart, Carlos Gonzales and Timmi Allen. Maxim Edwards and Jake Godin contributed reporting. Produced with input from Billy Burton and colleagues from the Cameroon Anglophone Crisis Database of Atrocities, with thanks to University of California Berkeley and the Exeter Database Team and Siham Ali.